Organization Trends

What Killed Michael Brown?: The Victim Hustle

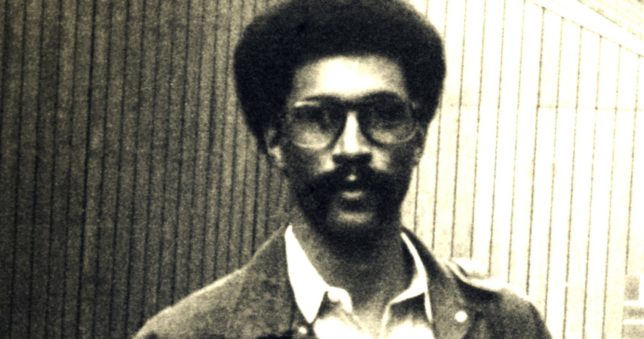

Shelby Steele in his black power days.

Shelby Steele in his black power days.

The Filmmakers of What Killed Michael Brown?

Michael Brown | Back to the 1960s | The Victim Hustle

Black Lives Matter | Going to War with Amazon

Summary: CRC’s Joseph (Jake) Klein interviews Shelby Steele and Eli Steele on their latest movie What Killed Michael Brown? and how liberalism has devastated the black community.

Watch the interview here.

KLEIN: I’d love to dive in on the psychology of that, because it seems to me to be the case that there is definitely an activist class, where it is power. They want to use this to achieve certain ends, but I wonder to what extent the desire for power is broadly representative of people that believe and push for these narratives and are seemingly trying to make the world a better place. And the people that want power are trying to make the world a better place, too. They’re just wrong. Right?

SHELBY STEELE: And whites don’t know they’re being hustled. I grew up in segregation, in an all-black, segregated community, segregated schools. There was no need to give me a talk. The fact that you now have to give kids a talk to let them know. All you’re doing is infusing them with fear and anxiety. You should give them a talk to tell them how free they are, what a blessing freedom is, how hard their people worked to win their freedom. But to sit a young kid down and say, “Oh, you’re going to run into this and it’s going to be hard for you, and you’re going to be overwhelmed.” This is suicidal. We’re killing off the spirit, the courage to go out in the world and make the world your oyster. Find yourself.

KLEIN: I completely hear and agree with what you’re saying there. I don’t think victimhood, when it’s not actually present, is psychologically healthy. But, nonetheless, it seems to be the case that the parents that are worried about having to have that talk with their kids. They’re not worried about broad societal power in that moment.

SHELBY STEELE: They are.

KLEIN: Oh, you think so?

SHELBY STEELE: I think so. I think it’s a part of the collective experience, the collective identity. If you’re black, the way you gesture your identity, is to claim victimization, claim that racism is systemic. It’s everywhere, it’s institutional, it’s structural, it’s just ubiquitous as the air itself. Because as you extend racism, this evil, what blacks are really doing is expanding their territory of entitlement. They’re saying, “You don’t just owe me for an isolated incident of a tragedy like Michael Brown. You owe me for systemic racism, so you’re in debt to me. And I’m owed, and I’m looking for preferences, I’m looking to be treated that way, to be offered things. I want entitlements.”

And so, we take our own history, the tragedy of our history and it’s all the victimization we endured, and again, we turn it into a hustle. We try to shake down the larger society. And we’re good at it. We’ve pretty much taken over education in America. Education is now taught from the point of view of black victimization. And whites are saying they don’t know what to do. They’re confused, they don’t see they’re being had.

ELI STEELE: In my own life, I’ve been pulled over by the police just because I fit the profile of some robbery or something that’s just happened. I’ve also had two separate incidents where the police pulled guns on me, one of them on the south side of Chicago—I almost got shot. Which—interestingly, when I tell that story—because I’m deaf, some people in the deaf community want me to turn that story into some story of a large victimization story. And part of me is like, well those incidents were almost like a perfect storm of things that I almost could fault the police officer. I mean, usually, when they find out that I’m deaf, they usually are stunned, and you can see the relief on their face. They had no idea. But they were trying to communicate with me or something like that.

But my point is that the power is to turn this—whatever power we have in the deaf community—is to turn that into some kind of a political coin and exploit that into something bigger. But then, what happens if I do that? I become trapped in that. I become the symbol for that victimization, and it comes at a personal cost to me. And then, I chose to take the point of view that, yes, that was tragedy. Yeah, it scared the crap out of me, but thank god the police officer was well-trained. They did not fire. They did not make a mistake. And I’m thankful for that. But it’s really interesting, because the way they feel it should go affects how you live your life.

KLEIN: I think that there’s multiple types of power that it would be useful to disambiguate. I think, when I hear you talking about power, it’s about people owing the community things. Right? So let’s call that, just for the sake of conversation right now, policy power. But I think there’s another type of power that might be relevant in this, which is psychological power, one’s own self-image. And I want to ask you about this because I grew up in the Jewish-American community, and what I found there, when I was growing up, was a lot of people complaining about anti-Semitism who I know never experienced anti-Semitism once in their life. I happen to think existing online anti-Semitism has gotten a little worse in the last couple years, but it’s still negligible. And certainly when I was growing up, none of my friends or family friends who were complaining about anti-Semitism were actually experiencing any.

But I don’t, that often, see Jewish-Americans asking for reparations or policy power sort of things. But when I tried to figure out what was going on there, the best explanation that I could come up with was it was sort of a search for a psychological power. A sense that, if anything goes wrong in my life—not anything, but certain things—I can blame it on my identity, and then I don’t have to feel bad about it. And then, when I do achieve things, I can feel a sense of I overcame something real hard, and I can feel even more rewarded mentally for it.

SHELBY STEELE: You got it. That’s my work.

KLEIN: Do you think that’s part of it, as well? And how would you weigh those against each other?

ELI STEELE: It should be from my father, just a quick thing is this huge lesson from the Holocaust. The best revenge is the life best lived. So if you want revenge over Hitler, if you want revenge, you live your life and you live your life the way you’re supposed to. You become somebody. My grandfather, real quickly, was in the Lower East Side, probably two or three years after the war, and he went into this tenement and all the were crying. They were still crying over family members that they had lost, and how much better life would be if those people were here. And so my grandfather basically said, “What are you crying about? What good is that going to do for you? You need to go to work. You need to do something now.” And so, that’s what he did, and almost everybody in that room died middle class or better. But they had to psychologically accept that they will never get justice.

SHELBY STEELE: Eli’s grandfather was a Holocaust survivor was a Holocaust survivor. Great man, learned a lot from him about this use of victimization as power. The tragedy of post-’60s liberalism in America is that we allowed, in our desire to redeem ourselves from the past, we thought we’d pay off victimization. And so, it became power to minorities. And so they claim victimization all the time, everywhere, at this point. And within universities, within corporations, there are HR departments that now insist on employees and so forth, as victims. And it’s transformed the curriculum in most universities. So it’s not an idle power; it’s extremely powerful.

Last year they eliminated the SAT at University of California for admissions because of the racial disparities in performance and so forth, so almost in honor of this victimization. Well, a society that keeps responding that way is going to destroy itself, going to eat [itself] up. My argument is, that if you come from a group, as I do, that had four centuries of oppression, you don’t need people to lower standards for you, you need people now to raise them. Ask us to perform at the same level or higher than everybody else. So this is, again, the perversion, the corruption that we try to get to in this film, and Michael Brown is a great example of it because the hunger of so many people in America who rush into this little town, Ferguson, and get a piece of that action, get a piece of that power, was dramatic, a dramatic, vivid display of this corruption that I think now threatens. You see it years later in the George Floyd demonstrations and so forth. I’m sure we’ll see it again.

In the next installment of “What Killed Michael Brown?,” they look at problems with Black Lives Matter.