Organization Trends

501(c)(4)s and “Dark Money”: Donor-Advised Funds

501(c)(4)s and the Etymology of “Dark Money” (full series)

Evolution of (c)(4)s | Origins of (c)(4)s | Regulatory Struggles

A Definition of “Dark Money” | Donor-Advised Funds | “Dark Money” Usage

Donor-Advised Funds

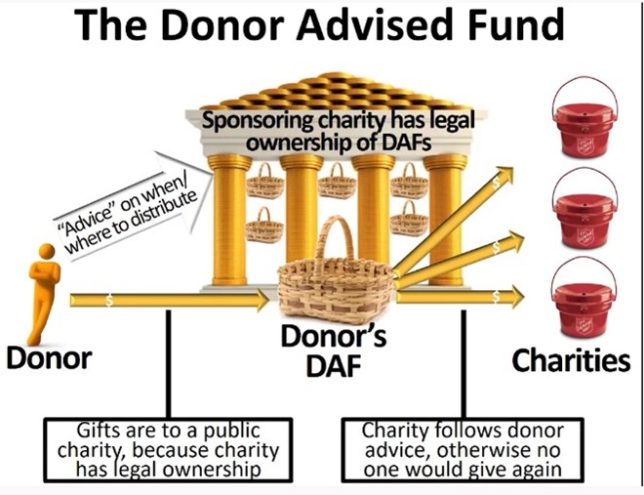

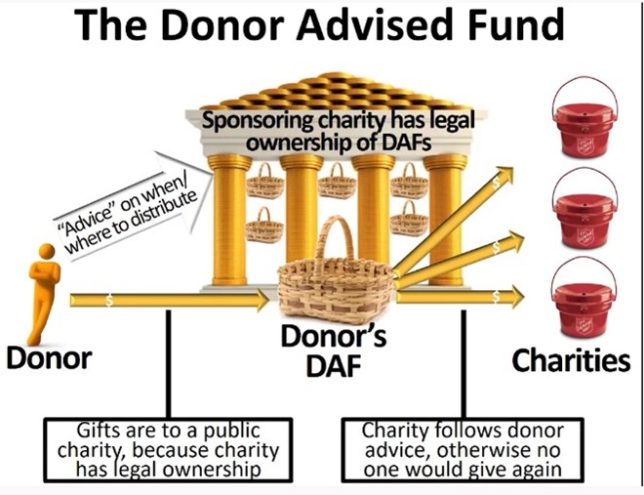

Another significant phenomenon in (c)(3) money flows is the use of donor-advised funds, also known as “DAFs,” which are the fastest-growing sector of philanthropy. DAFs allow a donor to deposit money into a personal account at an institution like the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund, then “advise” the institution to issue charitable grants from that account. The DAF provider (in this example, Fidelity) reports publicly that it has made a grant to the charity, but it does not publicly report who made the original donation. Even the charity receiving the grant may never know the original donor. If the lack of public disclosure is an important part of the definition of “dark money,” then these money flows also fit.

The largest DAF providers are not particularly ideological. They are operated by mutual-fund and money-management firms that have more experience investing money than giving it away, such as Fidelity, Vanguard, and Charles Schwab, among others. DAF providers on the left side of the ideological spectrum include the large Tides Foundation and a provider within the NEO Philanthropy range of products and services. Smaller, conservative DAF providers include DonorsTrust and the newer Bradley Impact Fund.

Undeserved Derision, Necessary Clarity

If lack of disclosure is the critical factor in “dark money,” other methods of funding that are sometimes called “dark” do not deserve the loaded term. For example, contributions to political candidates or to conventional political-action committees are not “dark.” Both candidates and regular PACs, as Bradley Smith has noted, must publicly disclose all donors whose aggregate contributions exceed $200. Smith made that point in response to recent attacks on supposedly “dark money” made by U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY).

Nor could grantmaking by 501(c)(3) private foundations ever be “dark,” for another example, even though Jane Mayer’s ally, Jill Abramson, has claimed in The Guardian that the Mercer Family Foundation gave away “dark money.” Abramson based her claim on the fact that the Mercer Family Foundation invested part of its assets in overseas accounts, even though such investments are entirely legal, and no one has accused the Mercers of illegally concealing any financial information. But most importantly, the Mercer Foundation, like all private foundations, is required to disclose all grantees and grant amounts in annual Form 990-PFs, which are filed with the Internal Revenue Service and easily accessible to the public from numerous websites.

Discretion

“[T]he discussion of candidates and issues as a political-campaign activity” was not “perceived as a major problem so long as the 501(c)(4) category was dominated by the political left,” IFS’s Smith observes. “Beginning in the 1990s, however, and especially since 2010, organizations that were more conservative began using the 501(c)(4) category to engage in public education as well as political activity, thus challenging liberal dominance in nonprofit advocacy.” (In the 2020 election cycle, interestingly enough, the Left and Democrats appeared to be use (c)(4) funding much more than conservatives and Republicans.)

Just as there may be ambiguity in the word “dark”—useful to many of the Left who took initial advantage of it, in their journalistic and polemical discretion—many want to see, and there may be, some ambiguity in the relevant statutory, regulatory, and administrative language constituting the (c)(4) framework. “Political,” “insubstantial,” “exclusively,” and “primarily” are all susceptible to parsing. Looking at the section’s origins, classifications, and the struggles over them is not dispositive. There’s room for attempts at advantage-taking here, too, keeping in mind what the IRS tried in the eyes of conservative groups denied (c)(4) status after Citizens United.

Finally, and relatedly, who can and should properly wield such discretion? The ACLU’s Dougherty concludes by discussing the two poles of how to deal with (c)(4) political activity—“prohibiting all activities or permitting it unfettered”—and recommends that, no matter what might be done, “it should be accomplished not by the Treasury Department, but rather by Congress.”

Smith’s Wall Street Journal piece on the proposed ’13 revisions points out:

The statute leaves it to the IRS to define ‘social welfare’ in that context, and for half a century the agency has defined it to include political-campaign activity. The 501(c)(4) category has always been the home of political-advocacy groups.” He concludes that “legislation is not required. The IRS could with its own rules follow the bipartisan FEC on the question of a group’s political status.

The (c)(4) definitional dithering may just be beginning. Or, will merely cantankerously continue. As probably will selective use of the term “dark money.”

Equal Application of the Term

If Smith is correct, if the term “dark money” has come to mean funds spent on speech or activities with which the user disagrees, then perhaps the term should be shelved. At a minimum, the public should insist that mainstream media use the term just as often to describe left-of-center donors’ giving as they do to describe giving by right-of-center donors. For as Hayden Ludwig of the Capital Research Center has documented, the Left has vast empires of “dark money” of its own.

In the next installment, see how the media and politicians use “dark money.”