Organization Trends

The State of Redistricting 2022: Update to the Proportionality Analysis

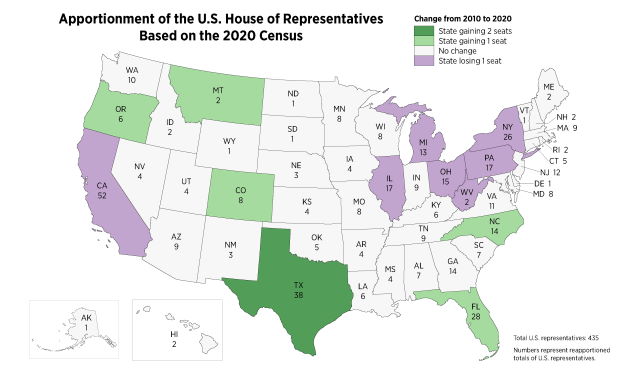

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

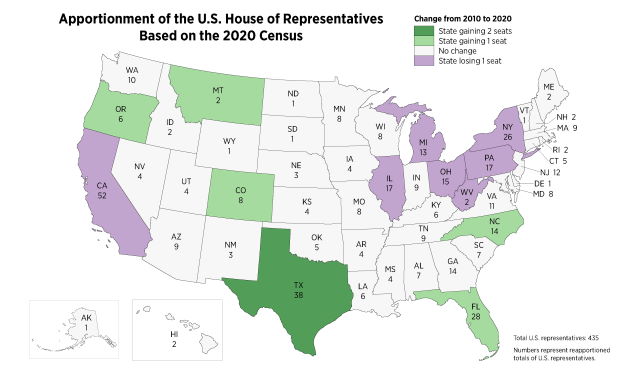

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

The State of Redistricting 2022 (full series)

Update to the Proportionality Analysis | Broken Commissions

The Coming Commissions | Power Players

Summary: Every decade, the federal Census determines the apportionment of congressional seats among the 50 states and compels states to reallocate the seats in Congress and state legislatures to ensure equal representation. The process of drawing the new district boundaries, known as “redistricting,” is profoundly political, and Democrats and Republicans—and their respective liberal and conservative outside allies—are locked in battles across the country to secure advantages in legislative elections for the next 10 years.

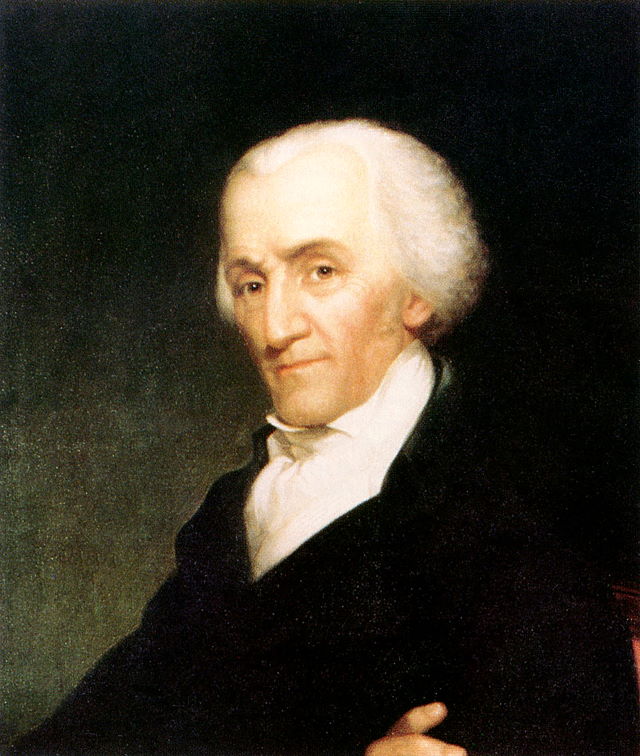

Since the government conducted the first Census in 1800, the representation in Congress has been apportioned every decade according to its outcome. With rare exceptions, states have apportioned representation through geographic districts dividing up the states, making control of those districts’ geographies a way to sneak in a partisan advantage in congressional and state legislative elections. This advantage was recognized as early as the First Congress, in which Patrick Henry’s anti-Federalist Virginia allies tried (unsuccessfully) to draw out then-Federalist James Madison. In the round of redistricting after the second Census in 1810, then-Gov. Elbridge Gerry’s Democratic-Republicans drew a salamander-shaped district that secured his party’s control of the Massachusetts State Senate, earning the practice the name “gerrymandering.”

In the round of redistricting after the second Census in 1810, then-Gov. Elbridge Gerry’s Democratic-Republicans drew a salamander-shaped district that secured his party’s control of the Massachusetts State Senate, earning the practice the name “gerrymandering.” License: Public domain.

Since 1929, the Permanent Apportionment Act has capped the size of the House of Representatives and placed no specific restrictions on how states shall draw congressional districts. From 1790 until 1911, the Congress passed a once-a-decade apportionment law setting the size of the House (usually expanding its size modestly) and in some cases (like the Apportionment Act of 1911) setting guidance on how districts should be drawn. But after the 1920 Census, Congress could not agree on an updated Apportionment Act, leading to wild disproportions in representation.

In 1929, Congress settled the matter for its part by passing the Permanent Apportionment Act. The act set the size of the House at 435 members, a number that has not changed except for two years after the admission of Hawaii and Alaska as states. Now, the apportionment automatically adjusts after the completion of each decennial Census, causing states that gain or lose seats to redraw their district boundaries. Supreme Court decisions since the passage of the 1929 Act further require that legislative and congressional districts contain equal represented populations. As a result, even states that do not gain or lose seats must adjust their district lines to ensure equal representation, unless they have only one seat elected at-large. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 placed additional constraints on redistricting to prevent dilution of ethnic minorities’ rights to representation.

The result is now a decennial ritual: State legislatures draw the new districts, often in a manner that their political opponents say resembles Gov. Gerry’s. From the 1960 redistricting cycle through the 2000 cycle, this strongly benefited Democrats, helping the party secure a “lock” on the House of Representatives, which it held from the 1954 elections until the 1994 elections. But now that Republicans have gained a foothold in state legislatures and secured the powers to draw large numbers of districts themselves, liberal groups like Common Cause, the League of Women Voters, and FairVote have sought to place the power of redistricting outside the normal political process—into “independent” processes unaccountable to voters and ripe for takeover by organized special interests that disproportionally fall on the political Left.

In truth, the only “law” of redistricting is Barone’s: “All process arguments are insincere, including this one.” The process of apportionment and representation is inherently political. Even assigning “technocratic” criteria to draw districts requires privileging some over others, a decision laced with political considerations.

We will now survey the landscape as states consider redistricting in advance of the 2022 elections. I start with an update of our previous work to determine the state-considered proportionality of congressional elections. I follow with an examination of how “independent” redistricting commissions, the favored approach of the Left in state-level campaigns and in federal legislation like H.R. 1. Yet redistricting commissions are compromised by vested interests, which we will then examine before drawing conclusions.

Update to the Proportionality Analysis

In 2020, the Republican Party made unexpected gains in the U.S. House of Representatives, even though the party failed to retake control of the chamber. Democrats and liberals naturally blamed gerrymandering, but the proportionality analysis showed the same outcome in 2020 as 2018: The Republican and Democratic coalitions in the hypothetical case of proportional results would be exactly equal in size to the actual results. In 2020, the test case showed each party holding one more seat in reality than it would in a hypothetical proportional-by-state allocation. The excess seats would go to the Conservative Party of New York (allied with the Republicans) and the Working Families Party of New York (allied with the Democrats), leaving the “party coalitions” equal in size in the test and real-world cases.

Further, the findings from the previous proportionality analyses concerning the effects of independent redistricting commissions continued to hold. California’s “independent” mapmaking, which was reportedly manipulated by the state Democratic Party, created a map that returned 10 “excess” Democratic seats. Despite Republicans recovering four seats relative to the 2018 elections, those gains only narrowed the “excess” to seven of the state’s 53 seats, a percentage deviation of 13 percent. That deviation is far out of line with the effect of the map the state’s “independent commission” generated through the full 2012–2020 districting period. In fact, it matched the average deviation from proportionality of the full period.

For comparison, in Texas—an open Republican “gerrymander”—the average deviation was 9 percent, and the deviation in 2020 was three seats, or 8 percent of the state delegation. Further, two (Arizona and Washington) of the other four states that used the Democratic model of “independent commissions” returned one “excess” Democrat, with Arizona returning more Democrats than Republicans despite Republicans winning more aggregate House votes in the state.

Republicans continued to pay the price for their New Jersey “dummymander.” The state’s map, drawn by a Republican-leaning commission of politicians, returned three “excess” Democrats of its 12 allocated seats, with the one change from 2018 being the defection of ex-Democratic U.S. Rep. Jeff Van Drew (R-NJ).

Connecticut’s and Massachusetts’ maps perfectly wipe out Republicans, who poll somewhere between one-third and two-fifths of votes in those states. Maryland, Illinois, and New York—all recognized Democratic gerrymanders—returned “excess” Democrats. Likewise, the Republican-drawn map in Ohio returned “excess” Republicans.

In short, if there is a “gerrymandering” crisis, the 2020 elections to U.S. House of Representatives failed to demonstrate it.

In the next installment, learn how “independent redistricting commissions” don’t work as advertised.