Labor Watch

The Era of Labor Reform and Unionism’s Height: The State of Big Labor, 1950

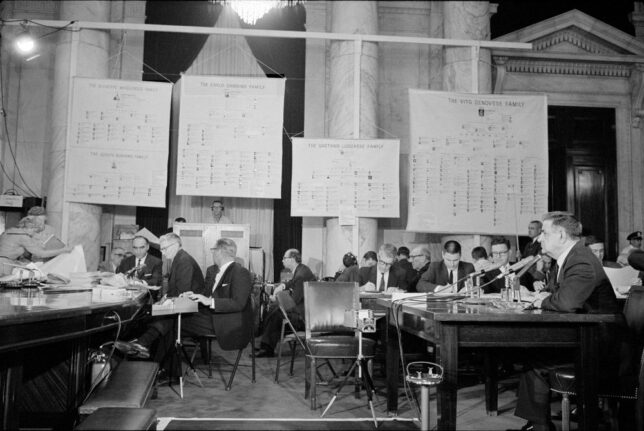

But a bigger and more pressing problem than infiltration by Reds was the infiltration of organized labor by wiseguys—Mafiosi. Credit: Marion Trikosko. License: https://shorturl.at/dpMTZ.

But a bigger and more pressing problem than infiltration by Reds was the infiltration of organized labor by wiseguys—Mafiosi. Credit: Marion Trikosko. License: https://shorturl.at/dpMTZ.

The Era of Labor Reform and Unionism’s Height

The Conservative Response | The State of Big Labor, 1950

Labor’s Compromised Right | Responding to the Rackets

The State of Big Labor, 1950

As the 20th century hit its midpoint, organized labor was both near its absolute height and riven by the issues that would start its long decline. At the forefront was unionism’s own division: The industrial-union Congress of Industrial Organizations and the craft-union American Federation of Labor remained divided, as they had been since the 1930s.

Communist domination of unions, especially in the CIO, remained a problem. Before Taft-Hartley had passed and enacted restrictions on Communists in union office (many of which would later be overturned by the Supreme Court), then–Screen Actors Guild president Ronald Reagan testified before Congress on his efforts to prevent the actors’ union and the film industry more broadly from succumbing to Communist control. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), representing dockworkers on the West Coast, was so committed to its Communist-backed leader Harry Bridges that even though the CIO kicked it out in 1950, Bridges stayed on as union president until 1976.

But a bigger and more pressing problem than infiltration by Reds was the infiltration of organized labor by wiseguys — Mafiosi. In an unusually American problem, organized crime syndicates began operating local labor organizations in exchange for kickbacks and manipulating their way to the top of regional and national labor unions. These “labor leaders” were little more than thieves, stealing from workers, employers, and the public alike through kickback schemes, “labor peace rackets,” and cartelization of local industries. Unions focused on economic choke points like the East Coast dockworkers’ International Longshoremen’s Association and truck drivers’ International Brotherhood of Teamsters proved ripe targets for Mafiosi at the midpoint of the century.

As these challenges faced organized labor, three powerful factions led by famous men were rising. In labor’s New Dealer–Cold Warrior center sat George Meany, the onetime plumber who rose to head the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and became a staunch ally of the Cold War–era Democratic Party. To Meany’s right sat James Riddle “Jimmy” Hoffa, the Mafia-compromised rising star of the Detroit-area Teamsters who would shortly lead the national union. To his left sat Walter Reuther, a United Auto Workers organizer who had flirted with Marxism (even working in the Soviet Union for a brief period in the early 1930s) before rising to lead the CIO and the activist-progressive wing of midcentury labor that would reach its height in power and influence during the 1960s.

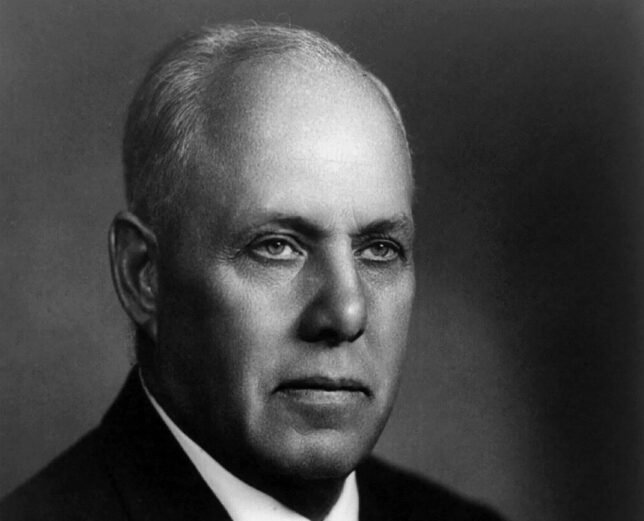

George Meany, the son of a local plumbers’ union president, followed his father into union organizing, becoming a local union business agent and later secretary of a building trades council. Credit: Albert Miller. License: https://shorturl.at/dxLNS.

George Meany’s Rise and the Creation of the AFL-CIO

George Meany rose through the ranks of organized labor in New York City. The son of a local plumbers’ union president, Meany took up the plumbing trade in his youth and followed his father into union organizing, becoming a local union business agent and later secretary of a building trades council. During the Depression, he rose to the position of head of the New York State Federation of Labor, where he learned and practiced the lobbying trade to secure passage of left-of-center economic legislation.

By 1940, he had ascended to the number-two position in the American Federation of Labor, and during World War II he sat as a member of the War Labor Board tasked with regulating the economic life of the country and preventing war-industry work stoppages. After V-J Day, the strike wave, and the 1946 Republican midterm sweep, Meany led the AFL’s unsuccessful campaign to defeat Taft-Hartley’s passage. He also aligned the AFL’s strategy to comply with the anti-Communist provisions enacted by the law.

In response to Taft-Hartley’s passage, Meany spearheaded the development of Labor’s League for Political Education (LLPE), the first AFL political committee and a counterpart to the CIO’s political action committee (which it had created to support President Roosevelt’s final campaign). The committee backed pro-union Democrats for Congress and legislative seats and President Truman’s election. When they took the majority and another term in the White House, the AFL and Meany demanded the law’s repeal. However, the Republican minority and its allies among union-skeptical southern Democrats defeated the repeal efforts, and the LLPE’s efforts to unseat Sen. Taft in 1950 failed miserably.

Meany’s disputes with the Truman administration over production and economic controls related to the Korean War and failure to reverse Taft-Hartley encouraged the AFL and CIO to narrow their rivalry. Such closeness was affirmed as the AFL and CIO old guards literally passed away: Philip Murray, head of the CIO, and Meany’s boss at the AFL, William Green, both died in November 1952.

Meany succeeded Green. Negotiating the merger opposite him would be Walter Reuther, longtime organizer and leader in the United Auto Workers and Murray’s successor leading the CIO. After nearly three years of negotiations, the modern AFL-CIO was codified in late 1955 with Meany as president.

As these negotiations were ongoing, Dwight Eisenhower had been elected president on the Republican ticket, the first presidential administration elected without the support of Big Labor since 1928. But in a sign of Big Labor’s power in the early 1950s, it was not clear that President Eisenhower’s administration would oppose expanding labor’s power. Eisenhower appointed the Plumbers Union’s Martin Durkin as his Labor Secretary and proposed union-friendly changes to Taft-Hartley.

Former Senator Joseph Ball (R-MN) wrote in the Foundation for Economic Education’s magazine The Freeman for September 1953, that Eisenhower and Durkin were “emasculating” Taft-Hartley with a set of 24 concessions to labor union interests.

In the next installment, union support for Republicans faded by the end of the 20th century.