Labor Watch

The Era of Labor Reform and Unionism’s Height: Responding to the Rackets

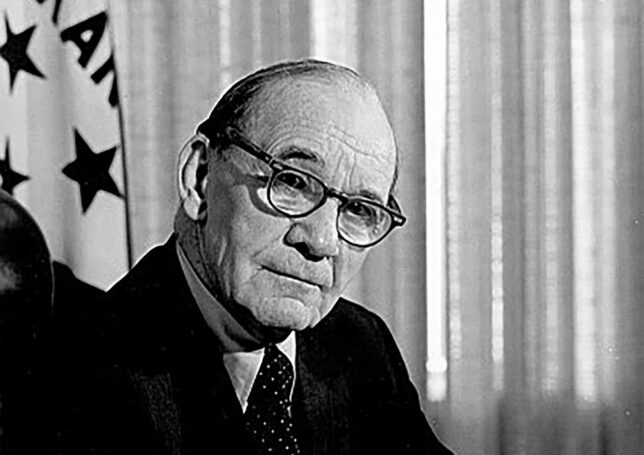

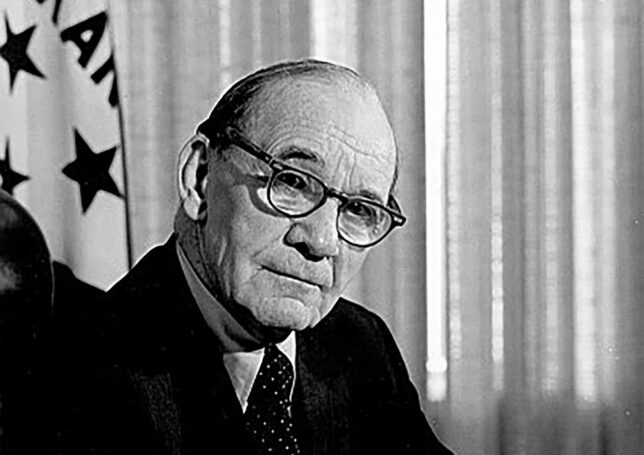

By 1959, the John McClellan Committee investigations and public hearings had exposed enough misbehavior by labor union officials (most of which was in the Teamsters Union) that a bipartisan consensus had emerged that something had to be done about it. Credit: U.S. Senate. License: Public domain.

By 1959, the John McClellan Committee investigations and public hearings had exposed enough misbehavior by labor union officials (most of which was in the Teamsters Union) that a bipartisan consensus had emerged that something had to be done about it. Credit: U.S. Senate. License: Public domain.

The Era of Labor Reform and Unionism’s Height

The Conservative Response | The State of Big Labor, 1950

Labor’s Compromised Right | Responding to the Rackets

Responding to the Rackets: The Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act

By 1959, the McClellan Committee investigations and public hearings had exposed enough misbehavior by labor union officials (most of which was in the Teamsters Union) that a bipartisan consensus had emerged that something had to be done about it. But pushing back against the power of organized labor did not come naturally to President Eisenhower, and the Democratic congressional majorities that had grown in size after the 1958 midterm elections were broadly labor-backed.

That said, the McClellan Committee’s revelations had made doing nothing to counter labor corruption politically untenable even for liberal stalwarts like Robert Kennedy’s brother, Sen. John F. Kennedy (D-MA). The AFL-CIO worked with Senator Kennedy on a mild corrective bill before the 1958 elections. It was defeated by business’s desire for a stronger bill and the Teamsters and some allied unions’ demand for no legislation at all. The increased Democratic majorities after the “six-year itch” elections in 1958 should have assured passage for a union-backed mild bill.

But it did not work out that way. In 1959, Kennedy’s bill was amended on the Senate floor to include a “union member bill of rights” backed by law professor Clyde Summers (who had drafted a version for the American Civil Liberties Union) and proposed by Senator McClellan, who had chaired the Rackets Committee. After the amended bill passed the Senate, the AFL-CIO, like Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters, came out to oppose the legislation in the House.

That decision put the legislative ball in the Eisenhower administration’s court. A tougher proposal was put forward by Rep. Phil Landrum, a Georgia Democrat aligned with the union-skeptical conservative coalition, and Rep. Robert Griffin, a Michigan Republican. With support from Department of Labor bureaucrat Howard Jenkins Jr., the pair devised legislation to regulate unions’ activities without the pro-union changes to Taft-Hartley found in the Kennedy bill.

With President Eisenhower’s backing, the Landrum-Griffin legislation was adopted in a House floor vote. After further negotiation, both Houses of Congress passed the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 along the lines proposed in the Landrum-Griffin bill.

The legislation attempted to directly respond to corrupt practices exposed by the Rackets Committee. The dubious practices of management consultants like Nathan Shefferman, the fixer for Teamsters boss Dave Beck, were addressed by placing reporting requirements on employer-hired professional operatives who interact with employees to discuss unionization and labor relations questions and by barring employers and employer agents from providing “things of value” to union officials. The Teamsters’ practice of shutting down dissidents opposed to Hoffa’s compromised union leadership or outright looting local unions by placing local unions in trusteeship was restricted. Other provisions established minimum standards of democracy in union officer elections and made union officers fiduciaries responsible for stewarding union funds “solely for the benefit of the organization and its members.” Union spending would be subject to scrutiny by requiring labor unions to submit financial disclosures subject to public inspection to the Department of Labor (though these requirements would be functionally toothless until the George W. Bush administration.)

Because the Landrum-Griffin rather than the Kennedy proposal was ultimately enacted, the law toughened regulations on union conduct from Taft-Hartley. It banned “hot cargo” contract clauses, under which an employer agreed with a union not to handle shipments involving a business involved in a labor strike. (The Hoffa-led Teamsters had abused “hot cargo” clauses to engage in labor racketeering.) Picketing for the purposes of union organizing was restricted but not banned outright as businesses had hoped.

The final law also kept Sen. McClellan’s bill of rights for union members in a modified form. Union members are guaranteed certain procedural and democratic rights related to union officer election, the setting of dues, speaking out against union leadership or policies, and due process in internal union discipline proceedings.

Toward the Great Society

In no small part because of the supporting role he played on the Rackets Committee and in developing the legislative response to it, Senator John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960. With a labor-backed Democratic trifecta coming into power, the public desire for regulation of unions in response to the 1950s corruption exposes satisfied, and the potential for new organizing in the growing government sector, the union movement entered the 1960s on a high, looking toward sunlit uplands.

But those uplands would never come. The immediate post–World War II economy had given unions structural advantages that would erode with time. The union movement had squandered its good name by surrendering large sections of itself to Communists and mobsters. The Great Society liberalism that Big Labor would midwife nationalized even more of labor unions’ more popular “offerings” to members and seeded a conservative backlash unseen since Warren Harding’s return to “normalcy” after the aggressive Progressivism of Woodrow Wilson.

Union membership peaked at roughly one-third of the workforce in the 1950s. The decade of reform that exposed organized labor’s seedy underbelly would be unionism’s height. The Long Decline was about to begin.