Labor Watch

Corruption in the Labor Movement: Labor Rackets

By the 1950s, Mafia domination and common thievery were so common among America’s labor statesmen that the U.S. Senate convened multiple investigative committees to determine the extent of corruption in the labor movement. Credit: LightField Studios. License: Shutterstock.

By the 1950s, Mafia domination and common thievery were so common among America’s labor statesmen that the U.S. Senate convened multiple investigative committees to determine the extent of corruption in the labor movement. Credit: LightField Studios. License: Shutterstock.

Corruption in the Labor Movement: From Wiseguys on the Waterfront to “Fat, Dumb, and Happy” and Beyond (full series)

Labor Rackets | A New Cast of Thieves

Philly’s Labor Fixer | Indictments

Corruption by labor union officials, whether in service to themselves, political allies, or organized crime syndicates, has been a fixture of American labor history since the labor movement first began to organize in the late 19th century. While the extent of criminal influence in organized labor has declined thanks to extensive federal law enforcement activity and judicial oversight, major corruption scandals continue to dog the union movement. From the recent kickback scheme at the United Auto Workers to the downfall of Philadelphia union boss and political fixer Johnny Doc Dougherty to the confession of former Teamsters boss John Coli, who was well connected to Chicago politicos, systemic corruption persists.

Corruption in American organized labor is nearly as old as formal labor unions in the United States. Most historians of labor corruption agree that employers had much to do in starting it: By hiring their own toughs to break strikes in the late 19th and early 20th century, employers induced labor organizers to go looking for their own bands of toughs. And the toughs the workingmen found were in many cases classic “wiseguys”—that is, Mafiosi.

What started as a marriage of emergency became metastatic cancer. The enforcers discovered that the real money was not in doing organized labor’s dirty work but in running the labor unions themselves. Backed by government-granted powers and close connections with government officials in places like the New York metropolitan area, the opportunities for graft schemes legal and illegal and multi-million-dollar rackets were nearly limitless.

By the 1950s, Mafia domination and common thievery were so common among America’s labor statesmen that the U.S. Senate convened multiple investigative committees to determine the extent of corruption in the labor movement. These investigations jump-started the careers of a young senator from Massachusetts and his Senate-staffer brother, both surnamed Kennedy. The investigations revealed that America’s largest labor union at the time, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, was led by one crook, Dave Beck, who would be replaced during the hearings by another, the infamous Jimmy Hoffa (whom readers may remember as a character in Netflix’s The Irishman).

Congress responded by passing the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act—federal legislation designed to expose labor racketeering—but the rackets continued to pass cold, hard cash from workers’ wages and benefit funds into the hands of the made men. Mafia control of major international labor unions—most prominently the Teamsters and Laborers—was not ultimately broken until the Mafia itself was challenged by a change in federal criminal justice priorities: The post–J. Edgar Hoover FBI aggressively investigated the Mob. Bipartisan majorities in Congress passed expansive laws against organized crime, culminating in the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO). And federal prosecutors engaged in creative lawfare against Mob-tied institutions. The most prominent was then-U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Rudolph Giuliani, whose civil RICO action against the Teamsters Union ended the Mafia domination of that union, at least at the international headquarters level.

But throwing the book at old-fashioned wiseguys only crimped one form—admittedly a major form—of organized labor corruption. America’s labor unions still provide the common thieves who have led some of them with ample opportunities to embezzle, taking workers’ dues and pension contributions for personal luxuries. Dirty employers or their corrupt agents continue to offer kickbacks to keep the labor bosses commissioned by the federal exclusive monopoly bargaining privilege to negotiate on behalf of their workers “fat, dumb, and happy.” Union bosses closely tied to Democratic political machines have been implicated in public corruption in Philadelphia and Illinois. While international unions are cleaner than they were in Hoffa’s day, rooting Mafiosi out of local labor unions has been more difficult, with federal prosecutors charging Columbo Family brass with extorting a labor union official just last year.

The Structure of Labor Rackets

Corruption in organized labor can be analyzed in two ways: by the beneficiaries and aims of a corrupt scheme and by the corrupt practices in which the corrupted union officials engage. There are three broad categories of schemes and any number of practices in which a corrupted union can engage.

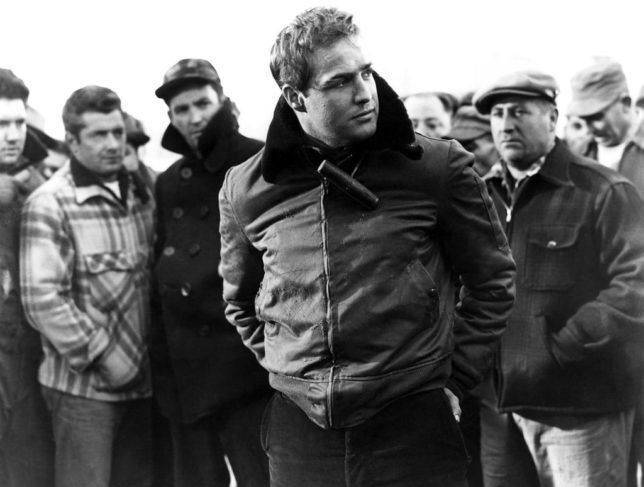

Sometimes, the union boss is little more than a common thief, stealing union resources or taking bribes from employers for his own personal benefit. Other union officials seeking power and influence cross the line from legal influence to bribery and other forms of political corruption or engage in violence and intimidation to achieve an otherwise legitimate union aim. The final class may be the best known, having been immortalized on the silver screen and American legend: the subordination of a labor union to organized crime, as depicted in the Marlon Brando classic On the Waterfront and the more recent Netflix feature The Irishman.

A final form of labor racketeering that deserves mention is the hiring-hall or shape-up racket, depicted in Brando’s Oscar-winning On the Waterfront. Credit: kerim. License: https://bit.ly/3WWBTEg.

Whatever the motive, the methods of improperly extracting funds or influence from a labor union are similar. Sometimes, the methods are technically legal: bloated salaries and multiple-officeholding by union bosses were characterized as “a kind of legalized graft” by James Jacobs, an academic scholar of labor racketeering.

Crossing the line into crime, sometimes the union officer just embezzles union funds or functions as an accomplice to a thieving superior by helping cover up the thefts. Former Washington Teachers Union president Barbara Bullock and two aides were convicted for a turn-of-the-21st-century scheme in which they bilked the union treasury for $5 million in funds they used to buy household luxuries and pay for personal services over seven years.

Thieves in union officer jobs have included Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters Union predecessor (and onetime “Republicans’ Labor Statesman”) Dave Beck, whom congressional investigators accused of using a labor-management consultant as a cut-out who would purchase personal luxuries for Beck with his supposed consulting fees. Ricky Freeman was a former SEIU local leader convicted of embezzlement for taking union funds for “elaborate personal expenses” including a wedding in Hawaii. Then there are the many names on the roll of dishonor that is the Department of Labor Office of Labor-Management Standards list of criminal enforcement actions.

The form of union corruption that even trade unionists will admit is a serious problem is the corruption of the union management by employer kickbacks. A corrupt employer can, to quote the indictment of former Fiat Chrysler executive Al Iacobelli, keep the union officials “fat, dumb, and happy” with bribes or other perks, giving the employer a more favorable negotiation while rank-and-file union members are none the wiser.

But sometimes, the employer is not only the perpetrator, especially when the union has been corrupted by organized crime. The classical “labor peace” racket loosely follows the form “nice business you have there, shame if my union were to strike it,” with the wiseguy union man expecting a payoff. The federal government suspected officials with the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE), a successor union to the famed International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), ran a racket on this model on behalf of various New York City-based organized crime families. In these schemes, employers are corrupted as well. In his history of corruption in organized labor Solidarity for Sale, left-wing journalist Robert Fitch reported that sources within the garment unions told him that the unions were not enforcing job-site safety agreements and minimum-wage requirements in exchange for bribes.

Running alongside mob-controlled unions are various forms of employer-cartel influence. Jacobs describes three: The mob could establish an employer cartel (and police it with other racketeering activities) to ensure businesses co-operated with the mob-influenced unions. The mob could create its own principal business within the cartelized industry, which it could then advantage by manipulating its union status. Or the mob could direct employers to do business with mob-controlled suppliers, with the supply contracts enforced by racketeering activity, such as labor peace extortion.

A final form of labor racketeering that deserves mention is the hiring-hall or shape-up racket, depicted in Brando’s Oscar-winning On the Waterfront. Through its control of job referrals (typically through a hiring hall, though the old longshore unions depicted in the film used the on-site “shape-up”), the corrupted union takes kickbacks from and exercises control over the unionized workers themselves. Critics of the corrupt leadership are sidelined, and corrupt business agents exclude from work union members who refuse to grease palms. In the June 2010 edition of Capital Research Center’s Labor Watch, Robert VerBruggen listed a number of examples of hiring-hall racket busts in the construction industry, which uses the hiring hall widely.

Enabling the union racket is the structure of American labor law, a point both right-leaning and left-wing observers of union corruption concede. Exclusive monopoly representation in enterprise bargaining—under which a single (exclusive) trade union negotiates for all employees, union members and not (monopoly representation)—at a single workplace or firm (enterprise bargaining) is uncommon in an international comparison, as is widespread American-style union corruption. Monopoly representation prevents competition among labor organizations (or individual representation) and in non-right-to-work states secures forced payment of fees from non-union-members. Enterprise bargaining makes the employer both a potential target for labor peace extortion and a potential co-conspirator in a contract-avoidance racket or negotiation kickback scheme.

Not coincidentally, economic choke points, especially goods transportation in trucking and shipping, have had some of the most historically corrupt unions. The ability to shut off economic activity creates numerous opportunities for extortion, and the proliferation of small enterprises allows other racketeering tactics to proliferate.

In the next installment, the federal government investigates United Auto Workers officials running a kickback scheme run through a training center.