Labor Watch

Creation of the Labor-Progressive Alliance: Never Let a Crisis Go to Waste

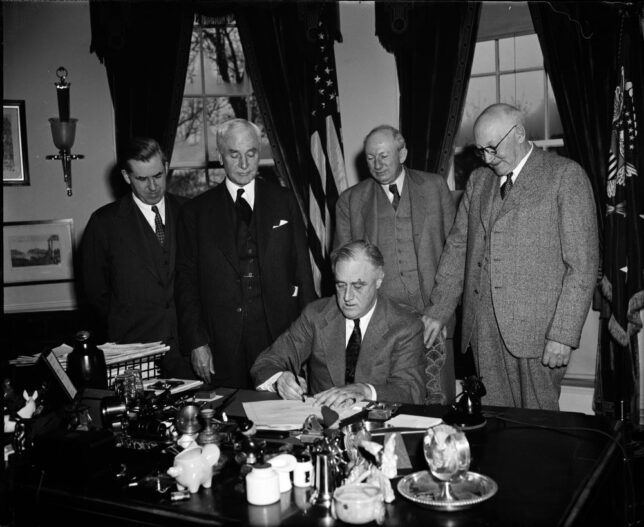

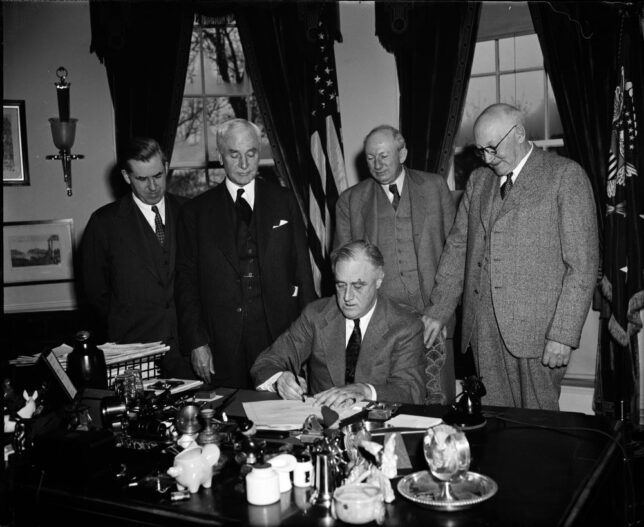

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal swept away the last vestiges of Gompers’s voluntarism, with national legislation compelling union recognition and bargaining, setting minimum wages and codifying work hours, and establishing national old-age insurance binding the union movement to the Democratic Party and its capital-P Progressive wing. Credit: Harris & Ewing. License: https://bit.ly/3K7IbMX.

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal swept away the last vestiges of Gompers’s voluntarism, with national legislation compelling union recognition and bargaining, setting minimum wages and codifying work hours, and establishing national old-age insurance binding the union movement to the Democratic Party and its capital-P Progressive wing. Credit: Harris & Ewing. License: https://bit.ly/3K7IbMX.

Creation of the Labor-Progressive Alliance (full series)

Industrialization and Labor Unionism | Why Unions Came to Be

Defining the Workforce | Never Let a Crisis Go to Waste

Never Let a Crisis Go to Waste: The New Deal Baseline of American Labor Relations

The 1920s passed with little of note for organized labor beyond the passing away of its previous leaders, both radical and business-unionist. Gompers was succeeded in 1924 at the AFL by former Ohio state legislator and mineworkers union official William Green, a supporter of cooperative relations with management under conditions of union recognition and collective bargaining.

When the economy went south after the Wall Street crash in 1929, organized labor’s power surged as the American workingman’s situation reached its own crisis point. Organized labor had already seen some increase in its power before the crash, with the first major federal labor-relations legislation, the original Railway Labor Act of 1926, which created a structure for arbitrating disputes between railroads and their employee unions.

But after the crash, federal backing for union organizing came quick and fast. In 1931, Congress enacted the Davis-Bacon Act, requiring union-rate “prevailing wages” in certain federally funded construction projects. In 1932, the Norris-LaGuardia Act, sponsored by Progressive Republicans Sen. George Norris (R-NE) and Rep. Fiorello LaGuardia (R-NY) and signed by Republican Herbert Hoover, prohibited contract provisions barring union affiliation (known as the “yellow-dog contract” to unionists) and further limited the use of anti-strike injunctions.

In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt took office with large congressional majorities committed to reshaping the American economy in response to the Great Depression. With Roosevelt came early organized labor’s Holy Grail: legislation to compel employers to recognize labor unions. The first attempt came as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), the Roosevelt administration’s omnibus economic central-planning package. Labor unions saw NIRA’s collective bargaining rules as too weak, and when the Supreme Court struck down NIRA as unconstitutional, pushed a tougher measure backed by Sen. Robert Wagner (D-NY).

Wagner’s legislation, known as the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), was signed by President Roosevelt in 1935. It compelled employers to bargain with labor unions that could demonstrate, either by a government-supervised election or the agreement of the employer, majority support of the relevant workers and granted unions extensive powers to seek redress against employer actions contrary to union interest (called “unfair labor practices”).

The passage of NLRA calcified the ongoing changes in how organized labor approached politics and government, with the labor movement more firmly joined to Roosevelt’s New Deal Democrats. In advance of the 1936 election, labor officials — but not the AFL’s Green — formed Labor’s Non-Partisan League to support Roosevelt’s re-election and to endorse other New Deal supporters with a new, permanent political infrastructure.

At the same time, the AFL was riven in two by dissension over industrial and business unionism. The industrial unions, led by John L. Lewis’s United Mine Workers, demanded increased involvement in industrial-style organizing within the AFL, forming a “Committee for Industrial Organization.” The AFL responded by throwing Lewis’s faction out of the federation. In 1938, the faction became the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The CIO unions, perhaps most notably the United Auto Workers, which led an occupation (the “sit-down strike”) of General Motors plants in Michigan, saw substantial gains in membership. With the NLRA’s power of the to compel recognition and friendly New Deal-influenced politicians unwilling to enforce employer powers, industrial unionism flourished.

The Roosevelt administration continued to support organized labor’s goals after the NLRA’s passage, effectively nationalizing a number of union aims through legislation. The Social Security Act of 1935 created a government-funded old-age pension and government-administered unemployment insurance. In the second Roosevelt term, since the administration could be sure the Supreme Court would uphold the law’s legality after the “switch in time that saved nine,” the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 codified the first federal minimum wages and set the standard working week at 40 hours (five eight-hour days), securing one of organized labor’s original goals.

The 1938 midterm elections saw the “conservative coalition” of Southern Democrats and Republicans form an informal faction in Congress that could block aggressive New Deal expansions. But the outbreak of World War II interrupted labor’s progress. Both the AFL and CIO agreed to a no-strike pledge after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into the war in exchange for influence in the central planning systems the Roosevelt administration created to manage war production, notably the National War Labor Board. Lewis, who had resigned from the CIO leadership in 1940 after he broke with the union faction to endorse unsuccessful moderate Republican Wendell Willkie against Roosevelt’s third campaign, left the CIO entirely in 1942. His United Mine Workers broke the no-strike pledge later in the war, leading to the Smith-Connally Act which allowed the federal government to temporarily nationalize plants important to war production to prevent strikes and banned direct union political contributions in federal elections.

In response to Smith-Connally’s limits and in advance of the 1944 elections, the CIO (now without John Lewis of the UMW, who had broken with the faction over Lewis’s personal loathing of Roosevelt) organized a new political innovation: the political action committee. In 1943, Sidney Hillman, the New York garment workers’ union leader, was tasked by the CIO leadership to head the new committee that would support Roosevelt’s fourth election campaign and his New Deal allies, known as CIO-PAC.

Communist Party USA members, who held numerous important roles in the CIO, were instrumental to CIO-PAC’s formation. John Abt, a former Roosevelt administration official working for Hillman’s Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union who admitted his Communist Party affiliation after his death, claimed that Communist Party official Eugene Dennis came to Abt and other CIO officials with a proposal for a committee to support Roosevelt’s re-election.

With CIO-PAC’s support, Roosevelt was re-elected. After Roosevelt’s death, Vice President Harry S. Truman, a nondescript former Senator who had replaced the very left-wing Henry Wallace on the Democratic ticket, succeeded to the office. In August 1945, Japan surrendered, ending the Second World War and the AFL and CIO no-strike pledges just as the millions of men called to arms were being demobilized and returning to civilian life.

Amid a surge in inflation as wartime central planning and rationing were lifted, organized labor called the largest strike wave in American history, with an estimated 10 percent of the American workforce walking off the job. Notable strikes took place in the auto industry, where UAW leader Walter Reuther led General Motors workers out for 113 days seeking not only wage and benefits increases but also control over GM’s retail pricing, which he was unable to secure.

The strike wave exacerbated the postwar inflation and threatened the political position of Truman and his Democratic Party. When railroad unions threatened a strike in early 1946, Truman openly threatened to draft strikers into the military.

As a political matter, it availed the Democratic Party not. The 1946 midterm elections saw a surge in Republican support and gave the GOP control of levers of federal power for the first time since the 1932 FDR landslide. That Congress, far from the “do-nothing” Congress of Truman’s re-election campaign materials and presidentially focused historical memory, would prove highly consequential to the postwar future of American labor relations and the development of organized labor’s alliance with full-spectrum Great Society liberalism and later contemporary left-wing woke-progressivism.

Conclusion

The story of organized labor’s development and rise to prominence from the end of the Civil War through the elections of 1946 is complicated. That the difficult, poorly paid, and often dangerous work of early industrial America would impel workers to join together to improve their conditions is unsurprising in retrospect, and its legacy lives on in the union campaigner’s adage that “a bad boss is the best union organizer.” But it is notable that broad, working-class motivation—as is common in European trade unionism—never had the workers’ exclusive loyalty, thanks to the strength of American individualism as expressed in union practice through craft and business unionisms.

But while craft unionists like Samuel Gompers sought to use worker power through voluntarist collective bargaining to obtain their ends, a combination of circumstances and the temptations of power to secure labor’s aims drove the movement into the political process. Despite the efforts of radicals like Eugene Debs to form socialist or “labor” parties, it would prove to be the arms of Progressive Movement-influenced Democrats, like Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, into which labor fell.

But even as political power gave organized labor victories on questions of compulsory bargaining, unemployment, old-age insurance, and the eight-hour day, its quest for more would bring it into conflict with the rising power of the postwar American consumer. And its victories, which were affirmed in national legislation rather than collective bargaining, made labor unionism’s economic offerings less necessary to the American worker. And as the 80th United States Congress prepared to convene, the labor movement would face scrutiny it had mostly avoided since the New Dealers took over—scrutiny that would prove overdue.

This article was first published in the March/April 2023 issue of Capital Research magazine.