Labor Watch

When the Labor Unions Fought Socialism

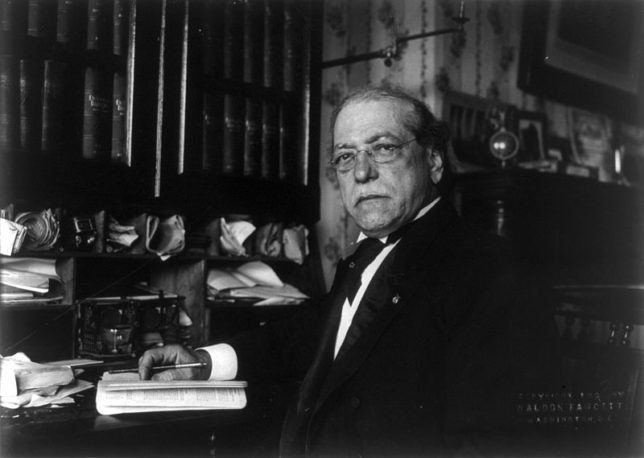

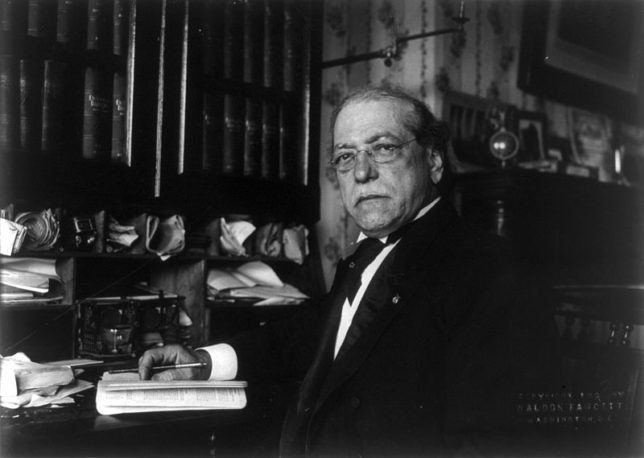

Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers

Today, labor unions, long an institution in the mainstream of the Democratic Party, are powerful advocates for the socialist Left. But it was not always this way. From the late nineteenth century through the Cold War, a much more powerful and politically independent (if still left-leaning) labor union movement—epitomized by the American Federation of Labor (later the AFL-CIO) under its leaders from Samuel Gompers to Lane Kirkland—was a bulwark of liberal anti-Communism. It supported American intervention against Communist rule in Asia and financially supported the Solidarity labor movement in Poland that helped usher in the collapse of the Soviet Empire.

Gompers, the founding president of the American Federation of Labor, perhaps unwittingly laid the foundations for this anti-socialist, pro-mixed-economy history by rejecting Marxist revolutionary thought in the late nineteenth century despite his commitment to working-class interests. Gompers wrote as early as 1877 (predating the AFL’s founding) that the working class should turn to “purely industrial or economical class organizations with less hours and more wages for their motto.” Then AFL president Gompers put this into practice by focusing on securing collective bargaining for union members rather than explicitly political activities like the Presidential campaigns of Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs.

Gompers’ opposition to socialist approaches cost him the leadership of the AFL for 1894; but in 1895, he returned to office with his collective-bargaining approach more firmly ensconced in the American union movement. In 1901, Gompers co-founded the National Civic Federation alongside Republican U.S. Senator Mark Hanna, a fixer for and ally of President William McKinley; NCF served as a forum for businesses open to negotiation with unions and labor activists. Gompers later allied with Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, supporting American intervention in World War I, a position opposed by the Socialist Debs.

After Gompers’ death, the union movement became more political, seeking government guarantees for private-sector collective bargaining which culminated in the New Deal-era National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). After NLRA’s passage, left-wing unions formed the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), with a commitment to a deeper alliance with President Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic Party.

That alliance had an Achilles’ heel. When Republicans took control of Congress after a major strike wave following the end of the Second World War, they passed the Taft-Hartley Act labor reform with support from conservatives in the Democratic Party, ending a number of privileges unions received in the original NLRA. That pushed the AFL, led by the center-left George Meany, and the CIO, led by the left-wing Walter Reuther, to reunify; Meany would lead the merged AFL-CIO. Meany, though an advocate of left-aligned mixed-economy labor regulations like subsidized healthcare, minimum wage hikes, and privileges for strikes and union organizing, said he “very much believe[d] in the free-market system.” Abroad, Meany was a staunch Cold Warrior, even withholding the federation’s endorsement from George McGovern in the left-wing stalwart’s 1972 challenge to President Richard Nixon.

Lane Kirkland, Meany’s successor, continued his center-left Cold Warrior path. Kirkland, who as Meany’s chief lieutenant backed the refusal to endorse McGovern and co-founded the second anti-Soviet Committee on the Present Danger, authorized $6 million in AFL-CIO aid to support the independent Polish labor union Solidarity, whose demonstrations would begin the end of Soviet control of Eastern Europe. Kirkland’s foreign policy earned praise from aides to Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch, who once told the Washington Post: “The AFL-CIO in general takes foreign policy positions to the right of Ronald Reagan.”

Throughout Meany and Kirkland’s control of the AFL-CIO, the union federation collaborated with the U.S. government in its efforts to counter Soviet influence over labor organizations abroad. Jay Lovestone, a reformed Communist, later became chair of the AFL-CIO Free Trade Union Committee (a rival international trade-union congress to the Soviet-backed World Federation of Trade Unions) and Meany’s “foreign minister.” He cooperated with CIA operative James J. Angleton in efforts to subvert Communist control of foreign labor organizations and to promote non-Communist free trade unions. By the 1980s, the U.S. government, through the Labor Department and National Endowment for Democracy, was providing overt support for Kirkland’s efforts to support independent trade unionism abroad, most prominently in Eastern Europe and Latin America.

But Big Labor had sowed the seeds of its far-left turn in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and by the mid-1990s they sprouted. Organized labor set the stage to break its liberal alliance with the managed-market economy and Cold War consensus foreign policy and to demand ever-increasing government control of the means of production. They wanted to expand collective bargaining unionism to the government sector after the passage of the first state-and-local-government worker collective bargaining laws in the late 1950s. The result was a rise in the share of the AFL-CIO and the union movement made up of government workers—workers not committed to the Gompers approach of recognizing capitalism’s legitimacy while fighting to increase labor’s share of capitalism’s spoils. Instead, the government worker unions saw an ever-expanding state as the path to lining their members’ (and the unions’ own) pockets.

By 1995, one of these government-sector union leaders, then-Service Employees International Union (SEIU) president John Sweeney—who reportedly joined the Democratic Socialists of America to show he would be more aligned with the Left than Kirkland—took control of Meany’s and Kirkland’s old federation, having been elected with the support of other government worker unions like AFSCME.

Today, labor unions represent a diminishing faction of American economic life, and one that largely relies on government largesse. Only 10.5 percent of American non-agricultural workers are union members; nearly 49 percent of American union members—7.16 million of 14.74 million—are government workers, as of 2018 data compiled at the Union Membership and Coverage Database. One consequence of unions’ decline from mainstream mass movement to factional special interest has been political radicalization.

In its 2018 annual disclosures filed last week, the SEIU declared contributions to the political organizations Progressive Congress Action Fund and Peoples Climate Votes; the far-left think tank Demos; and the controversial left-wing political consultancy Revolution Messaging—all key organizations of the socialist-leaning “progressive movement.” While the SEIU may have left the AFL-CIO, it continues Sweeney’s red revolution in the labor movement. Sweeney may had hoped his changes would restore union power and membership, but the opposite has proved true.