Organization Trends

National Lawyers Guild: The Civil Rights Movement and the New Left

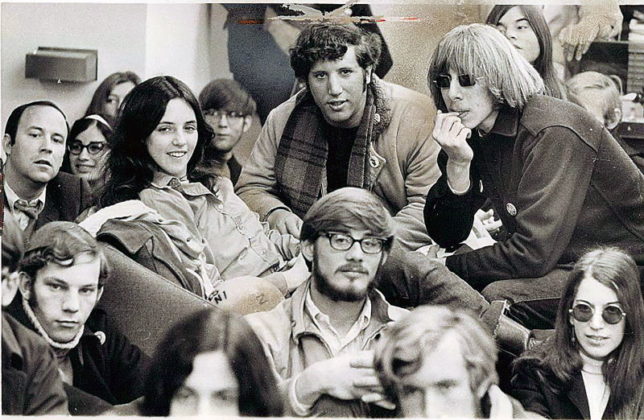

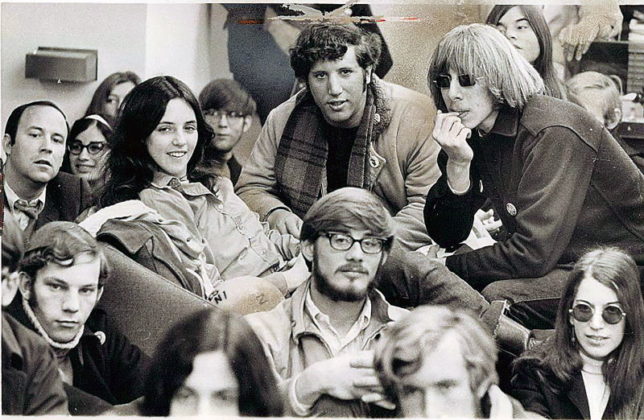

In the 1960s, most new members of NLG were young, and many were associated with the New Left movement and the radical groups Students for a Democratic Society and Weather Underground. Credit: Wystan. License: https://bit.ly/3kJOxVc.

In the 1960s, most new members of NLG were young, and many were associated with the New Left movement and the radical groups Students for a Democratic Society and Weather Underground. Credit: Wystan. License: https://bit.ly/3kJOxVc.

National Lawyers Guild (full series)

Origins and Early Years | The Second Red Scare

The Civil Rights Movement and the New Left | Consolidation and Internationalism

Activities and Positions | Leadership, Structure, and Financials

The Civil Rights Movement and the New Left: 1960–1973

The National Lawyers Guild was the first racially integrated national bar association in the United States, and actively opposed military segregation during World War II. A number of notable civil rights attorneys, including future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, were Guild members. John Conyers and George Crockett, both of whom would later represent Michigan in the U.S. House of Representatives, were also active in the NLG’s civil rights work in the early 1960s. In 1962 the NLG created the Committee to Assist Southern Lawyers (later renamed the Committee for Legal Assistance to the South), in order to provide legal support to the civil rights movement in the Southern United States. All Guild members were asked to provide unpaid assistance to southern attorneys if it were requested of them. At a special convention held in February 1964, the NLG voted to make civil rights work in the South its primary mission.

NLG members were active in the 1964 Freedom Summer project, which sought to promote voter registration among Mississippi’s largely disenfranchised black population. Seventy volunteers, including four NLG board members, signed up to provide assistance to the project through handling civil rights cases. Ultimately, the Committee for Legal Assistance to the South handled 45 cases and represented 315 defendants over the course of the Freedom Summer project. NLG members were also instrumental in founding the Center for Constitutional Rights in 1966.

The New Left and Protest Support. Due in no small part to its civil rights work in the South, NLG membership began to grow beginning in 1966. Most new members were young, and many were associated with the New Left movement and the radical group Students for a Democratic Society. Historian Harvey Klehr wrote that “by 1967, [the NLG] had become the legal arm of the New Left and was intimately involved in radical activities.” At the Guild’s 1968 convention, it adopted a resolution declaring itself to be “the legal arm of the movement.”

This period of growth coincided with, and was related to, a sharp escalation in American involvement in the Vietnam War. At its 1965 convention the NLG passed a resolution opposing the war and offering legal assistance to any who objected to participating in it. By 1967, the Guild “was concentrating much of its effort on selective service and military law.” It eventually opened offices in the Philippines, Japan, and Okinawa for the purpose of providing free legal counsel to military servicemembers who opposed the war. Attorney Michael Ratner remembered how the NLG was unique in the way “it not only defended people opposed to the war, it condemned the war and stood in solidarity with the Vietnamese people.”

Domestic protests also became a focal point for Guild activities, and its offices ultimately provided advice and representation to thousands of arrested protesters during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The NLG’s New York City chapter defended many of the student demonstrators at the Columbia University protests of 1968. The defendants in the Chicago Seven trial of 1969, which stemmed from protests and riots that had taken place during the Democratic National Convention the year before, were represented by NLG attorneys William Kunstler and Leonard Weinglass.

A team of NLG attorneys traveled to New York in order to represent inmates who were being prosecuted for their roles in the Attica prison riot of 1971, which had resulted in the deaths of 43 people. Many Guild attorneys were also involved with the Wounded Knee Legal Defense-Offense Committee, established to support the American Indian protesters who occupied Wounded Knee, South Dakota for more than two months in 1973.

The NLG’s Mass Defense program, which today constitutes a significant portion of its work, has its origins during this period. According to the NLG, beginning in 1966 the Black Panther Party engaged in armed patrols, later known as “copwatch,” to monitor the behavior of the Oakland Police Department in California. Reacting to the 1968 Columbia University protests, the Guild drew upon this practice to develop its Legal Observer program, training volunteers to monitor law enforcement actions at protests and to support arrested demonstrators.

According to Klehr, prominent NLG attorney William Kunstler wrote in 1975 that “the thing I’m most interested in is keeping people on the street who will forever alter the character of this society: the revolutionaries.”

The Weather Underground and Other Extremists. At the NLG’s 1967 convention in New York, Bernardine Dohrn was elected as student organizer, and at its February 1970 national convention she led a panel discussion on women and the NLG. Dohrn had been elected as the “inter-organizational secretary” of Students for a Democratic Society in 1968, but by the time she spoke at the NLG’s convention in early 1970 she was serving as one of the leaders of a violent extremist offshoot of the group called the Weather Underground (also known as the Weathermen).

Dohrn was placed on the FBI’s list of ten “Most Wanted” fugitives in October 1970, but was removed three years later after federal proceedings against her were dismissed. By 1975, the Weather Underground claimed to have conducted at least 25 bombings. Though the group ultimately pivoted to a strategy of non-lethal bombings, according to journalist Bryan Burrough in his 2015 book Days of Rage, the first two and a half months of 1970 was “the period, bluntly put, when Weatherman set out to kill people.” Although no murders have been tied to the Weather Underground bombings, a police officer was severely wounded in a February 1970 detonation.

While most NLG members were not involved in violent groups or activities, Dohrn was not the only one who was. Weather Underground member Russell Neufeld was an editor of the NLG’s Midnight Special prison newspaper. Judith Alice Clark, who served 37 years in prison before being granted parole in 2019 for her role in the deadly 1981 Brink’s armored car robbery perpetrated by members of the Black Liberation Army and the Weather Underground offshoot May 19th Communist Organization, also worked with the NLG.

Some NLG members functioned as a critical source of funds for the Weather Underground. According to Burrough, a group of radical attorneys in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles were “by far the most important single source of money” for the Weathermen. Almost all of these lawyers belonged to the NLG. One of them told Burrough that “you gotta understand, honey, we were lawyers, but we were revolutionaries in our hearts…we would’ve done anything for these people…This was the revolution, baby, and they were the fighters.”

Though Burrough wrote that approximately a dozen attorneys were mentioned as key Weather Underground supporters, only a few acknowledged it. Dennis Cunningham was one, admitting that “I gave them money, sure, and I raised even more.” Michael Kennedy, a member of the NLG’s San Francisco and New York City chapters, was “by far the most important attorney in Weatherman’s support network,” according to Burrough. Kennedy was close friends with Bernardine Dohrn, and also with NLG attorney Leonard Boudin, who was the father of Weather Underground member Kathy Boudin and grandfather of San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin.

Guild attorney Charles Garry represented Black Panther Party co-founders Bobby Seale and Huey Newton during the late 1960s, including defending Newton against murder charges related to the killing of a police officer. Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter, but that conviction was later overturned on appeal, and two subsequent trials ended with hung juries.

In 1977, Garry became counsel to cult leader Jim Jones and his Peoples Temple. Garry visited the cult’s Jonestown camp in Guyana, initially remarking that “I have seen paradise, where there is no sexism, racism, ageism, elitism, no one hungry.” He was present at Jonestown in 1978 during the mass murder-suicide of more than 900 Peoples Temple adherents, narrowly escaping death himself.

The Old Left Versus the New. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the NLG as an organization shifted away from its older longtime members and towards the new young activists. This change was rapid and profound. In 1968, a majority of attendees at the Guild’s national convention were members of the NLG’s founding generation. By early 1971, these older members had become a minority. This trend was accelerated by the admission of law students as full Guild members in 1970, and of legal workers and jailhouse lawyers the following year. During the period from 1968 to 1971, most of the NLG’s members were between the ages of 25 and 40, while its leadership was between 55 and 70.

This caused considerable generational strife. Victor Rabinowitz, NLG president from 1967-1968, remembered that “to many of us, these 25- to 30-year-olds seemed undignified, contentious, noisy, undisciplined. The generational differences were startling and deep.” Still, Rabinowitz argued that “those of us who are Marxists” should welcome the new young members, because “in their emphasis on the freedom of the individual, perhaps the young are looking to the ultimate goal of Communism rather than to the intermediate state of Socialism.”

At the Guild’s 1970 convention, approximately 50 younger members who could not afford the price of the formal dinner being served prior to the evening’s events were forced to wait outside the dining room while the other convention attendees ate. This prompted protests and calls for “future Guild conventions to be conducted in a place and style in conformity with the new membership.” What became known as the “Banquet Dinner Riot” featured scenes of Guild members guarding the banquet hall doors to prevent their hungry comrades from sneaking in to grab plates of food, and attorney William Kunstler burning his dinner ticket as a gesture of solidarity.

There were political conflicts between the two generations as well. The younger members were broadly associated with the New Left, and according to Doris Brin Walker (who became president of the NLG in 1970), they brought with them “Maoist influence, rancor toward the Soviet Union and anger toward the Old Left, which had failed to construct anything approaching a peaceful world or an ideal society.” Disputes among the Guild’s various far-left ideological factions became intense during this time. Nevertheless, there was enough unity on the NLG’s overarching purpose for it to declare in 1971 that “there is no disagreement among us that were are a body of radicals and revolutionaries.”

Many of those from the Old Left generation became less active in the NLG during this time, and by the 1970s the organization’s leadership largely consisted of law students or young lawyers who had only been practicing for a short period of time. A 1987 history of the Guild explains that as a consequence of this there was a scarcity of “mature leadership” in the organization for several years, during which it lost “the accumulated skills and experience of all but a handful of founding members.”

In the next installment, during the 1970 the guild consolidated its political philosophy of anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-capitalism, and anti-imperialism.