Organization Trends

National Lawyers Guild: The Second Red Scare

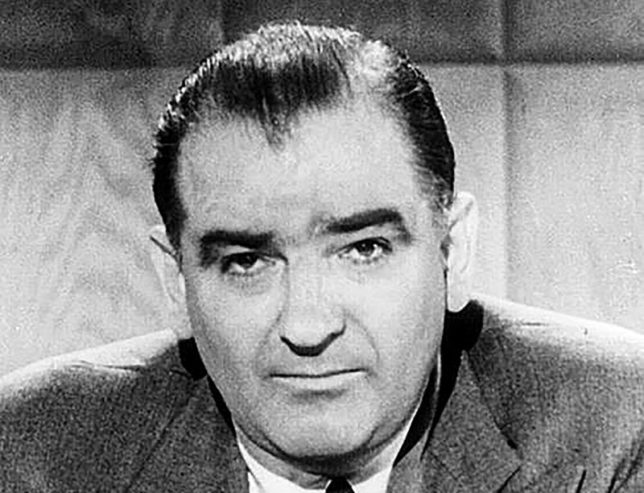

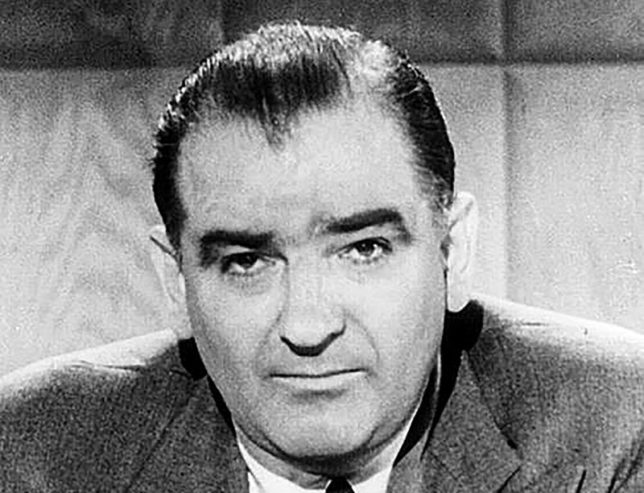

The markedly heightened anti-communist sentiments and fear in the United States of Communist control in parts of the world after World War II was simply called “McCarthyism,” after the most visible Congressional proponent of anti-communist investigations, Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI). Credit: Rupert Colley. License: https://bit.ly/3M4ZoVu.

The markedly heightened anti-communist sentiments and fear in the United States of Communist control in parts of the world after World War II was simply called “McCarthyism,” after the most visible Congressional proponent of anti-communist investigations, Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI). Credit: Rupert Colley. License: https://bit.ly/3M4ZoVu.

National Lawyers Guild (full series)

Origins and Early Years | The Second Red Scare

The Civil Rights Movement and the New Left | Consolidation and Internationalism

Activities and Positions | Leadership, Structure, and Financials

The Second Red Scare: 1947–1960

The years following the Second World War were characterized by markedly heightened anti-communist sentiments and fear in the United States, as the Soviet Union took control of its “satellite” states in Eastern Europe, Mao Zedong’s Communist forces took control of mainland China, and Communist North Korea invaded anti-communist South Korea. This is often simply called “McCarthyism,” after the most visible Congressional proponent of anti-communist investigations, Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI). The period is sometimes referred to as the “Second Red Scare,” with the “First Red Scare” having occurred in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and the First World War.

In 1947 President Truman signed Executive Order 9835, which established a program for investigating the loyalty of federal employees. This included examination of any affiliation with groups designated by the Attorney General as “totalitarian, fascist, communist, or subversive.” The National Lawyers Guild saw Executive Order 9835 as “outrageous” and designed “to control the thoughts and limit the freedom of association of all employees in government, including attorneys.”

Representation of Communists. The willingness of Guild members to represent communists in several high-profile investigations and prosecutions during the late 1940s and early 1950s, combined with strong anti-communist sentiments in Congress and among the public, drew considerable attention to the National Lawyers Guild. Perhaps the most famous case was that of Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were represented by NLG members.

In late 1947, ten Hollywood film writers refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and were cited for contempt. Historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes wrote that most of these “Hollywood Ten” were indeed secret communists, but they refused to invoke their Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination and simply declined to answer the committee’s questions. The Hollywood Ten were represented by NLG attorneys Ben Margolis, Charles Katz, Robert Kenny, Martin Popper, and Bartley Crum; all ten were ultimately imprisoned.

From 1948 to 1949, eleven CPUSA leaders were indicted and tried under the Smith Act, which criminalized advocating the violent overthrow of the United States government. All were convicted and sentenced to prison terms ranging from three to five years. Five NLG attorneys who represented the defendants—George W. Crockett, Harry Sacher, Abraham Isserman, Richard Gladstein, and Louis McCabe—were cited for contempt after the trial, and also imprisoned for a time.

FBI and Congressional Investigations. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) began surveilling the NLG as early as 1940 and would continue to do so until 1975.

According to historian Ellen Schrecker, the FBI illegally entered the Guild’s Washington, D.C. office at least fourteen times between 1947 and 1951. In a 1989 lawsuit settlement, the FBI admitted that “it appears more likely than not” that a number of unauthorized break-ins occurred, that agents copied organizational records while inside, and that they wiretapped the NLG’s headquarters office phone without a warrant. The FBI ultimately turned over approximately 400,000 pages of information it had collected on the NLG as part of that litigation.

Judith Coplon, an employee at the U.S. Department of Justice, was arrested in 1949 and charged with espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union. Though the evidence against her was strong and she was found guilty, her convictions were overturned on appeal due to the illegal investigative methods employed by the FBI.

The NLG analyzed material that was released through the Coplon trial, and eventually concluded that “the FBI may commit more federal crimes than it ever detects.” A Guild report on the FBI’s activities and methods had almost no impact, however, due to the almost simultaneous announcement of a HUAC investigation of the NLG as an alleged communist front organization.

This was not the first time HUAC had looked at the NLG. In September 1939, the committee had asked CPUSA general secretary Earl Browder about the Guild and the nature of its relationship to the Communist Party. A 1944 committee report appendix, detailing information on alleged communist front organizations, described the NLG as a “highly deceptive Communist-operated front organization, primarily intended to serve the interests of the Communist Party of the United States, through its activities among the legal profession.”

In September 1950, the committee released its “Report on the National Lawyers Guild: Legal Bulwark of the Communist Party.” It charged the NLG with being “an arm of the international Communist conspiracy,” and recommended that the Department of Justice list it as a subversive organization. The committee expressed its view that the NLG’s “attacks on the [FBI] are part of an over-all Communist strategy aimed at weakening our Nation’s defenses against the international Communist conspiracy.” It also suggested that the American Bar Association consider whether NLG membership “is compatible with admissibility to the American bar.”

Though attempts were made to do so, the NLG was ultimately never listed as subversive. In a speech at the national convention of the American Bar Association in August 1953, Eisenhower administration Attorney General Herbert Brownell stated he intended to list the group. Five years of protracted litigation followed, and in 1958 the Justice Department ultimately decided not to list the NLG as subversive. It made the same determination again in 1974.

Membership in the NLG dropped precipitously during the 1950s. Numerous guild members resigned “within days” of the publication of HUAC’s report. An official history of the guild puts total membership in 1955 at 500, while historian Guenter Lewy gave a figure of about 600 for 1956. According to the NLG, the organization’s efforts during the 1950s were largely directed at defending “itself against HUAC, the Justice Department, Senator McCarthy and other forces of Cold War.”

“Have You No Sense of Decency, Sir?” The Guild was indirectly involved in a famous verbal exchange that is sometimes given as heralding the decline of “McCarthyism.” While publicly questioning United States Army special counsel Joseph N. Welch at a hearing in June 1954, Senator McCarthy announced that a member of “the legal arm of the Communist Party” — a reference to the NLG — was employed as an attorney at Welch’s law firm. The lawyer, Frederick Fisher, had briefly been a member of the NLG during law school, and this prior association had led Welch to remove him from the firm’s work representing the Army at the McCarthy hearings.

Welch replied that “until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness,” defended Fisher, and implored McCarthy to “not assassinate this lad further.” He then asked McCarthy: “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency? Public opinion was reported to be decidedly in Fisher’s favor, and it was rapidly turning against McCarthy, who was censured by the Senate later that year and never recovered politically.

In the next installment, guild membership grew due largely to its civil rights work, but becomes increasingly aligned with extremist organizations.