Doing Good

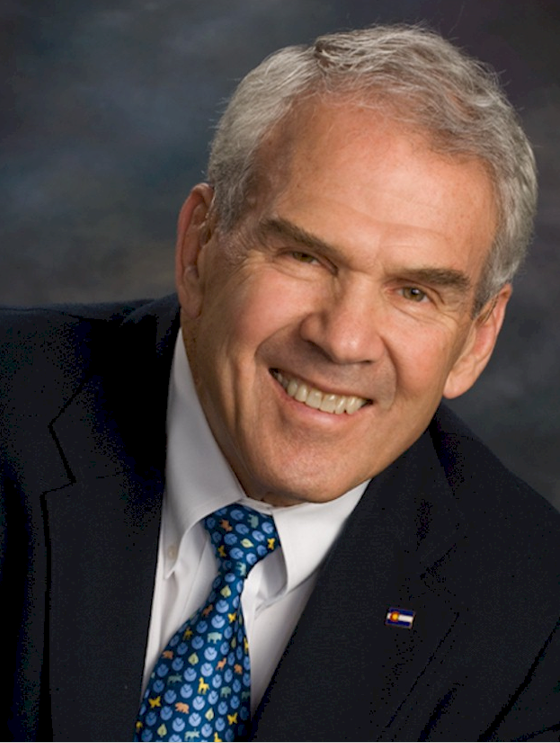

A Sit Down With a School Choice Champion: Meet Steve Schuck

A Sit Down With A School Choice Champion (full interview)

Meet Steve Schuck | Political Aspirations | Empowering Parents | Foundations and Figures

Following his graduation from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Stephen M. Schuck was the head football coach for a year at The Manlius School, the West Point prep school in upstate New York, and then got his first job in business at a large manufacturing firm in New York City. “I got caught up in the bureaucracy,” Schuck remembers. “You’re on a sort of predetermined schedule and I chafed under that kind of regimentation, and I got fired on Christmas Eve.”

When he had been coaching upstate, some players on the football team taught Schuck how to ski. “I just absolutely fell in love with skiing. It became an absolute passion,” he said. So, when he was at the job he so disliked in New York City, he would walk over to the New York Times building and purchase a copy of the Denver Post and Rocky Mountain News. Schuck, with a new son and pregnant wife at the time, would “apply for every job in Colorado.”

Schuck had never been west of Philadelphia, but he knew he wanted to go west, specifically to Colorado. While nothing ever came of his responses to the help-wanted ads in the Colorado papers, through a series of other coincidences, he found a potential job in Colorado Springs. It would be as assistant to the owner of a small department store. He was invited to Colorado Springs so the two “would test each other out for a couple of weeks,” as the winsome Schuck tells the story, “to make sure it was a good fit before moving my family out.”

It was February 1961. “I was wearing a heavy wool suit and heavy overcoat. I thought I was going to the Arctic Circle. I got off the airplane, and it was a typical Colorado day—you know, 50 to 60 degrees, blue sky. Just like it is today.”

Schuck was going to live in the basement of the man’s house, next to Colorado Springs’ famous Broadmoor Hotel. “I unpack and he said, ‘Why don’t you take the dog up for a walk around the hotel?’ I do that, and there are guys playing golf in shorts, people are swimming in a pool behind plexiglass, and I could see people skiing all within walking distance of where I was going to be living.”

“I went to the drug store, called my wife, and said, ‘I’ve been here for about an hour,’” Schuck said laughing, “’and I don’t give a damn if he fires me tomorrow morning, I’ll find a job sweeping floors. You can’t imagine how beautiful this place is.’ That started the love affair.”

Schuck and his family took the risk. He worked for the man for about 18 months before quitting. More risk. “I’ve got to be my own boss,” Schuck says engagingly. Since then, as his own boss, the now-82-year-old “blue-sky” Schuck has been a successful real-estate developer, a candidate for the state’s Republican gubernatorial nomination in 1986, an aggressive education-reform activist and founder of the Parents Challenge organization in Colorado Springs, a philanthropist in his own right and onetime board member of the Daniels Fund in Denver.

The colorful Coloradan’s breadth and depth of experience in business and entrepreneurship, in politics and policy, especially in education, and in philanthropy are difficult to match. His wisdom and insights are well-earned, well-expressed, and well worth reading—and heeding.

Below are edited excerpts from a conversation Schuck was kind enough to have in January with Michael E. Hartmann, director of the Center for Strategic Giving at the Capital Research Center.

In Real Estate, More Risk

Hartmann: How did you begin to generate your wealth?

Schuck: Real estate is the only field I knew about in which you could control your own destiny and could enter without any money, without any capital. By that time, I started as a salesman, I met a few people, had some relationships, and got a real start brokering commercial properties. The natural evolution is to progress from doing it for other people to doing it for yourself or for groups as a principal, so I started setting up investment groups doing our own development. I became focused on land, only because the guy who sort of took me under his wing was a land player.

I became very comfortable with and successful at assembling small groups of private investors to invest in and develop land. I’d be active and they’d be passive. They put up the money and I did the work. I got a piece of the action, and I found out that I was a natural at that because so much of that activity is relationship-driven—relationships with investors, with municipalities, and with users of the properties. My personality made this all a good fit. And for 50 years, we’ve done it in Colorado Springs, Denver, Phoenix, and Portland.

Hartmann: What was the nature of your business, and how did it affect your financial stability?

Schuck: It is extremely high-risk. Land developers make a commitment to acquire property and then spend hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars, on what we call “soft work”—planning, engineering, zoning, all of that long before we know whether government will approve us. And you don’t know what the final product will be until you’ve gone through the entire process. We have to anticipate what the market might want years before our finished product will be ready for the market.

Wayne Gretzky used to say, “I don’t skate to the puck. I skate to where the puck is going to be.” Yeah. Well, we don’t plan for what’s going on in the market today or even tomorrow. We have to plan for what the market will want when our product is finally completed or when our approvals are granted, and that’s measured in years, not weeks or months or quarters, as is more typical for other businesses.

All the money goes out in advance, before any comes back. It isn’t like you can spend 20 percent or 30 percent of your money and get 10 percent or 20 percent of it back incrementally. It’s all out and nothing back for a long time. The rule of thumb in our world is that you make 80 percent of your profit on the last 20 percent of your sales, so it’s extremely high-exposure.

Hartmann: How did all this affect, or how is this all related to, your overall worldview?

Schuck: Most people don’t have an appetite for that high level of risk. In our world, there’s a disconnect between when you create the value and when you monetize it, when it is actually realized in dollars and cash flow. You have to be comfortable with that. Most people aren’t, because they don’t like to or just don’t think that way. You have to have a very high tolerance for risk. So we fill a niche. We play an important intermediary role.

We can get the timing wrong, which I have done three or four times now. I’ve been on the wrong side of the curve, so that when our product was finally ready for the marketplace, the marketplace had no interest in it. The market demand for our product is not elastic. When there is demand, the market will pay whatever it has to, but when there is no demand, the market will not pay anything. I’ve gone broke several times. Doing so doesn’t bother me a bit, though it can be embarrassing and humiliating, and very tough on my family. I could not have survived without a supportive wife.

We developed a fairly high profile at one point. We had about 150 employees. We had the largest commercial brokerage company in Colorado Springs. We had 60 percent to 70 percent market share in our brokerage operation. Today, we outsource much of what we formerly did organizationally and are compact, mean, and lean.

Hartmann: From whom did you learn in the business?

Schuck: While I always sort of marched to my own drumbeat, the person who influenced me most was Bill Daniels. He was a friend, partner, and mentor from whom I learned much about life and what is really important.

In the next segment of his interview, Steve explains how his business acumen led him to politics.