Doing Good

Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross

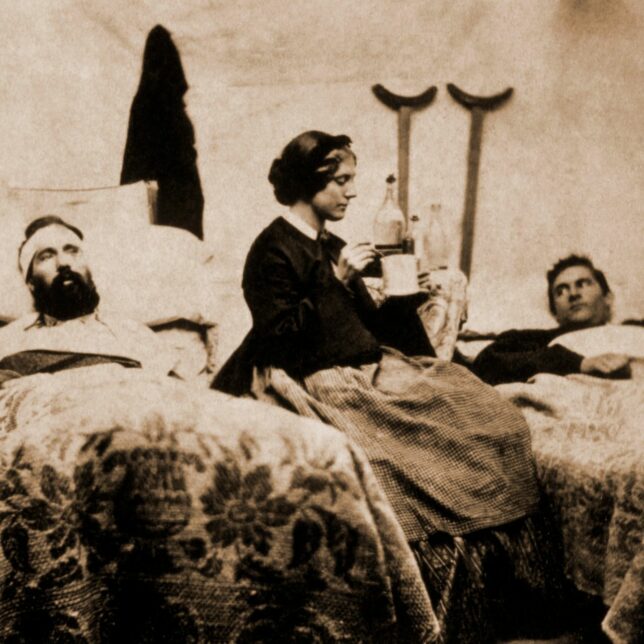

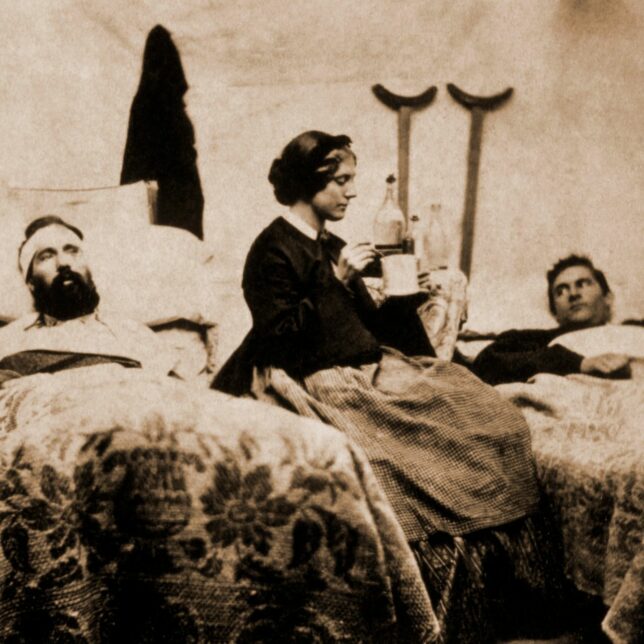

Clara Barton. License: Public domain.

Clara Barton. License: Public domain.

On the northern edge of Antietam Battlefield stands a monument to Clara Barton honoring her for bringing “supplies and nursing aid to the wounded” during the battle.

This was not the first time she had given aid to wounded soldiers. Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War, she had gathered food and medical supplies for injured soldiers of 6th Massachusetts Infantry at the U.S. Capitol Building. They had been moved to the U.S. Capitol Building after they were attacked by Southern supporters on April 19, 1861, in what became known as the Riot of Baltimore.

Barton continued to organize relief efforts in Washington, DC. In 1962 she received official permission to render aid on the front lines, which she did repeatedly until the Civil War ended three years later. She and her wagons of supplies seemed to unerringly appear on the front lines when and where they were most needed.

“Angel of the Battlefield”

Brigade Surgeon James Dunn of the 109th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry described her efforts in a letter to his family:

I first met [Miss Clara Barton] at the battle of Cedar Mountain, where she appeared in front of the hospital at 12 o’clock at night, with a four-mule team loaded with everything needed, and at a time when we were entirely out of dressings of every kind, she supplied us with everything; and while the shells were bursting in every direction, took her course to the hospital on pour right, where she found everything wanted again. After doing everything she could on the field, she returned to Culpepper, where she stayed dealing out shirts to the naked wounded, and preparing soup, and seeing it prepared in all the hospitals. I thought that night, if heaven ever sent out an angel, she must be one; her assistance was so timely. When we began our retreat up the Rappahannock, I thought no more of our lady friend, only that she had gone back to Washington. We arrived on the disastrous field of Bull Run, and while the battle was raging the fiercest on Friday, who should drive up in front of our hospital but this same woman, with her mules almost dead, having made forced marches from Washington to the army. She was again a welcomed visitor to both the wounded and the surgeons.

The battle was over, our wounded removed on Sunday, and we were ordered to Fairfax Station. We had hardly got there before the battle of Chantilly commenced, and soon the wounded began to come in. Here we had nothing but our instruments, not even a bottle of wine. When the cars whistled up to the station, the first person on the platform was Miss Barton, to again supply us with bandages, brandy, wine, prepared soup, jellies, meal, and every article that could be thought of. She stayed there until the last wounded soldier was placed on the cars, then bid us good bye, and left.

I wrote you at the time how we got to Alexandria that night and next morning. Our soldiers had no time to rest after reaching Washington, but were ordered to Maryland by forced marches. Several days of hard marches brought us to Frederick, and the battle of South Mountain followed. The next day our army stood face to face with the whole force. The rattle of 150,000 muskets, and the fearful thunder of over 200 cannon, told us that the great battle of Antietam had commenced. I was in a hospital in the afternoon, for it was then only that the wounded began to come in.

We had expended every bandage, torn up every sheet in the house, and everything we could find, when who should drive up but our old friend Miss Barton, with a team loaded down with dressings of every kind, and everything we could ask for. She distributed her articles to the difference hospitals, worked all night making soup, all the next day and night, and when I left, four days after the battle, I left her there ministering to the wounded and the dying. When I returned to the field-hospital last week, she was still at work, supplying them with delicacies of every kind, and administering to their wants, all of which she does out of her own private fortune.

Now, what do you think of Miss Barton? In my feeble estimation, Gen. McClellan, with all his laurels, sinks into insignificance beside the true heroine of the age, the angel of the battlefield.”

Red Cross and Geneva Convention

After the war, she went on a lecture tour speaking, not of “the glories of conquering armies but the mischief and misery they strew in their track.” She then traveled to Europe to recover from the exhausting tour. There she became aware of the International Red Cross and the Geneva Convention.

Inspired by her experiences, she founded the American Red Cross in 1881 and served as its president until 1904. At her urging, in 1882, President Chester Arthur Congress signed the Geneva Convention and the Senate ratified it a month later.