Green Watch

Federal Land Withdrawals:

Where Our Account Was Overdrawn

The Consequences of Locking Up American Mineral Wealth

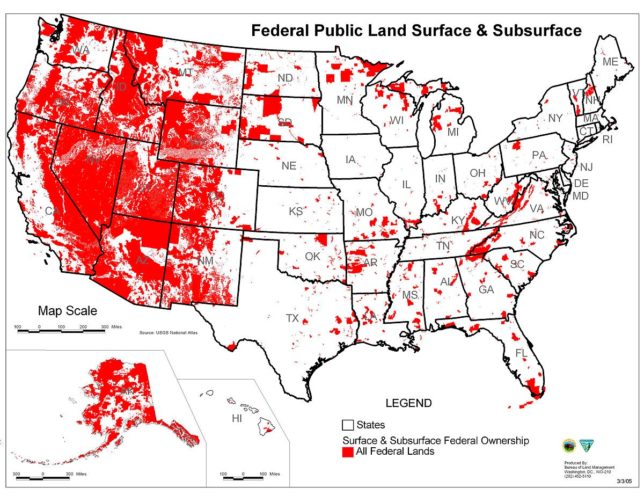

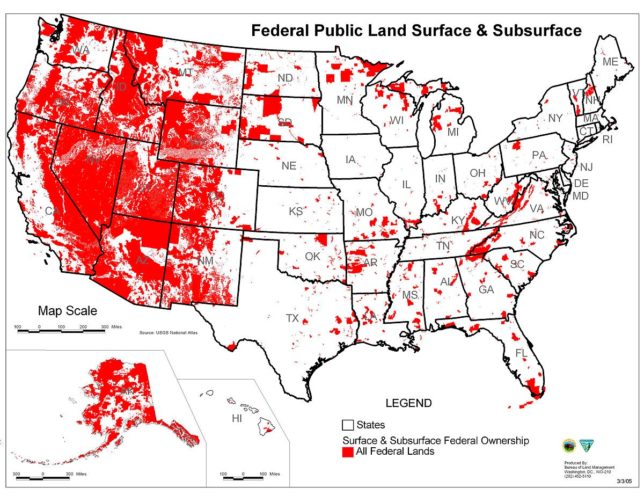

Figure 2. Surface and Subsurface Federal Land Ownership and Management Across the United States. Source: U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

Figure 2. Surface and Subsurface Federal Land Ownership and Management Across the United States. Source: U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

Where Our Account Was Overdrawn

Federal Land Withdrawals (full series)

Endangering the Nation | How Our Account Was Overdrawn

Where Our Account Was Overdrawn | Can We Ever Correct the Record?

Summary: Despite a wealth of resources within the boundaries United States, the U.S. economy and national defense rely on imports of critical minerals from China, Russia, and other unsavory or less reliable sources. The mineral resources of the United States could fill these needs, but most of these resources are located in federal public lands that have been withdrawn from exploration and mining.

Where Our Account Was Overdrawn

Much of this withdrawn land is in the American Cordillera, the mountain ranges in the western United States and Alaska where mineral deposits of economic significance are most likely to occur. In fact, no other belt of metallic deposits on earth is comparable to the American Cordillera.

The Obama administration dramatically accelerated the amount of withdrawals by invoking the Antiquities Act a record 29 times to establish or expand national monuments. The Obama administration was also the first to use the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act to withdraw coastal and offshore areas from mineral leasing activities.5 In January 2017, the incoming Trump administration faced several extremely large land withdrawals containing incredible amounts of mineral resources, that were rushed through at the eleventh hour of the outgoing Obama administration.

One proposed withdrawal, later scrapped in October 2017 by the Department of the Interior, was the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) plan to protect the greater sage-grouse and its sagebrush habitat.6 If enacted, this withdrawal would have placed a whopping 10 million acres of federal land off limits to exploration and mining in favor of habitat preservation across Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Wyoming.

Putting that into context, 10 million acres is equivalent to the total area of Rhode Island, Delaware, and Maryland, and the proposed withdrawal would have been similar to a federal edict compelling those states to halt all business and industry. However, these 10 million acres are not contiguous. They are checkerboarded over vast areas, impacting neighboring lands and perhaps effectively tripling or quadrupling the initial withdrawal acreage.

Other examples7 of possible politically based mineral withdrawals include:

- The Arizona Strip Uranium Withdrawal. In January 2012, President Barack Obama’s Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar withdrew more than 1,000,000 acres of land containing valuable uranium deposits and more than 3,200 active mining claims. The withdrawal area includes enough uranium (325–375 million pounds) to power the entire state of California’s 40 million people for over 20 years.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture identified this mineral withdrawal as a potential burden to domestic energy production. A December 2017 lawsuit challenged the withdrawal as illegal, but the Ninth Circuit Court upheld the withdrawal and the Supreme Court in October 2018 declined to review, leaving the withdrawal in effect.8

- The Minnesota Superior National Forest Land Withdrawal. On January 5, 2017, in the waning days of the Obama administration, the U.S. Forest Service formally proposed a 234,328-acre federal mineral withdrawal of Superior National Forest lands within the Rainy River Watershed for a 20-year term. The proposal immediately placed this vast area off limits to all mining development for up to two years while the withdrawal was considered.

The total withdrawal application boundary spanned approximately 425,000 acres, including 95,000 acres of state school trust fund lands. Minnesotans across the state have supported general redevelopment of the state’s mining industry and specifically the Twin Metals mining project in the withdrawn area. Government officials on both sides of the aisle publicly opposed this withdrawal.

More than 50 members of the Minnesota Legislature expressed outrage at the Forest Service’s decision to publish a notice of intent, triggering an environmental impact statement under NEPA law. In May 2018, the revoked mining leases in that area were to be fully reinstated, and in June 2018, President Donald Trump announced that the withdrawal would be formally canceled. Finally, the BLM in May 2019 renewed the leases that had previously been canceled.9

- The Oregon and California Railroad Lands Withdrawal. In December 2016, the Obama administration proposed a 101,000-acre withdrawal of Forest Service and BLM land astride the Oregon-California border, which would block mineral entry and exploration for 20 years, to take effect on January 17, 2017.

This area contains two mining projects believed to hold significant quantities of several critical minerals including nickel, cobalt, and scandium, which the United States is import-reliant 60, 70, and 100 percent, respectively. The Obama administration argued that this mineral withdrawal was valid under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), but it was not because the withdrawal order greatly exceeded 5,000-acre maximum under FLPMA and therefore required congressional legislation under FLPMA. However, no such legislation has ever been introduced.

Accordingly, the chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee requested the secretaries of Interior and Agriculture on September 28, 2017, to review the legality of the withdrawal.

- The California Desert Area Withdrawal. On December 28, 2016, the Obama administration proposed to withdraw 1,337,904 acres of public lands in the California desert and threatened a Phase 2 that could trigger the withdrawal of an additional 1,600,000 acres from minerals entry for 20 years. On February 6, 2018, BLM formally canceled the proposed withdrawal and the Phase 2 extension and opened the entire acreage to mining.

Surprising to most, half of the nation’s federal hardrock minerals are already off limits for development. This disproportionately restricts access to critical minerals because the western states account for 75 percent of all U.S. metals mining—mostly on public lands—according to the National Mining Association, which has long held that excessive and poorly chosen land withdrawals hurt the mining sector.

However, the October 2017 decision to scrap the sage-grouse withdrawal was a major positive step forward regarding exploration and mining in those now unrestricted areas covering parts of six western states.10

Instead of further withdrawing lands, the U.S. could better compete with the world’s other mining economies by opening public lands to even more domestic exploration and mining, which would translate into finding and producing additional minerals, a stronger manufacturing base, and a more secure national defense.

Thoughtless land withdrawal creates an ongoing risk of artificial shortages, setting up the need to import those same resources instead—exactly the situation the nation finds itself in today regarding critical mineral imports.11

Bennethum and Lee made clear:

[T]he power to withdraw lands from the operation of the public land laws, including lands that are subject to the Mining Law of 1872 and the 1920 Mineral Leasing Act, is one of the most important governmental powers affecting the mining industry. The mineral potential of an area is of no value if the area has been put off limits to mineral exploration and development. Yet, withdrawals are one of the least appreciated and understood government powers.12

The federal government owns and manages roughly 664 million acres of surface land and subsurface mineral rights, roughly 28 percent of U.S. land area. The location and total area of those lands are shown in Figure 2. More than 90 percent of those lands are in 12 western states: Washington, Oregon, California, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Alaska. And they contain the world-class mineral deposits of massive economic significance shown in Figure 1, mostly on federal lands.

Benethum and Lee demonstrated that by 1975 nearly 400 million acres have been withdrawn through governmental actions from the operation of the Mining Law of 1872. More than another 100 million acres are “encumbered” or are being managed in such a way as to constitute a de facto withdrawal from mineral development previously discussed That is a total of nearly 500 million acres withdrawn from the lands that fall under the jurisdiction of the Mining Law of 1872.13

One major reason this situation has occurred is the lack of any mechanism to assess the cumulative impact of thousands of discrete withdrawal actions. Each interest group working to withdraw more land does not consider the cumulative impact of its and other groups’ successful efforts. This kind of a land-use strategy, if it even deserves that label, is economically unsound and simply very detrimental public policy.

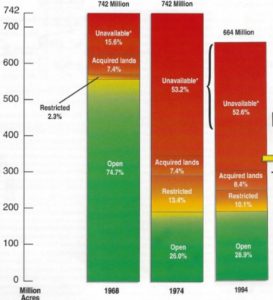

Figure 3. Public Lands Excluded from Mineral Exploration and Mining over the Last 50 Years. Lands “unavailable” for exploration and development increased dramatically after passage of NEPA in 1970. Source: American Mining Congress and Paul K. Driessen.

By the mid-1990s, 71 percent of the total federal acreage was off limits to mineral exploration and mining. Those acreage figures continued to creep higher until 2017, when the Trump administration stemmed the increase and started to reverse the process.14 For now, no more federal lands will likely be withdrawn, unless and until order can be brought to the existing chaotic process.15

As shown in Figure 3, roughly 29 percent of the 664 million acres under federal management were open to mineral access under the Mining Law as of 1995—and that might seem like an enormous chunk of land. However, most withdrawals neglect the simple fact that mineral deposits and mines are located where geology, not mankind, dictates.16 Some of these withdrawals may have been driven by the geology with the intent to check any future mining—if so, that would be most unfortunate and a betrayal of the mining laws on the books.

In the next installment of Federal Land Withdrawals, find out how to secure our mineral future.