Labor Watch

Creation of the Labor-Progressive Alliance: Defining the Workforce

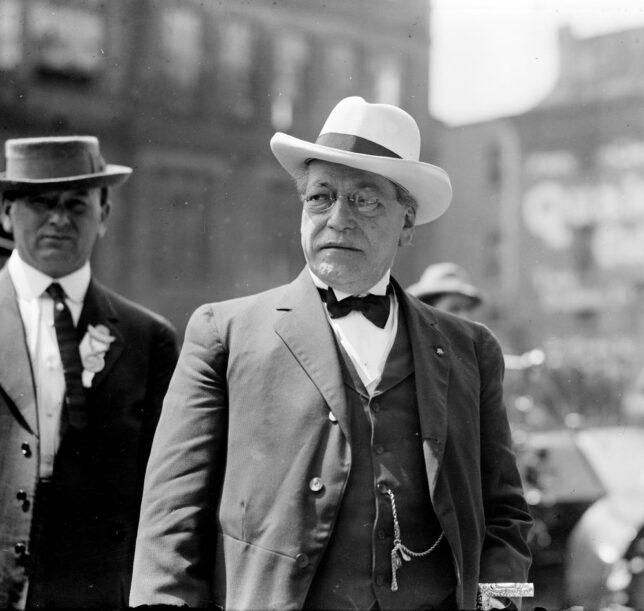

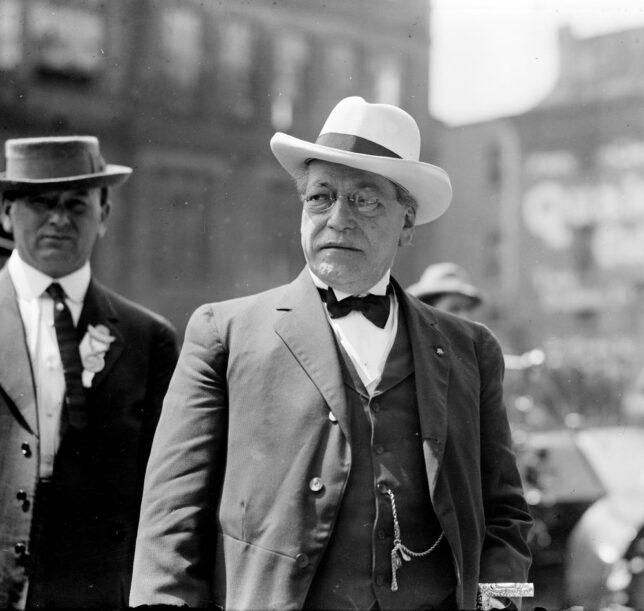

The American Federation of Labor was organized at a convention of trades unions convened in December 1886. Samuel Gompers, then an official in the Cigar Makers International Union, was elected the federation’s president. Credit: Bain News Service. License: https://bit.ly/3z4LGgF.

The American Federation of Labor was organized at a convention of trades unions convened in December 1886. Samuel Gompers, then an official in the Cigar Makers International Union, was elected the federation’s president. Credit: Bain News Service. License: https://bit.ly/3z4LGgF.

Creation of the Labor-Progressive Alliance (full series)

Industrialization and Labor Unionism | Why Unions Came to Be

Defining the Workforce | Never Let a Crisis Go to Waste

Defining the Workforce: Industrial vs. Craft Unionism

Aiding Gompers’s shift from Marxist-influenced radicalism to the capital-P Progressive mainstream of the early 20th century was a debate within organized labor that continues to the present day. Should the workers be organized on lines of job description or “craft”—for instance, as welders, fitters, machinists, and so on—or by industry, with all workers in that industry or working for a given industrial firm bargaining and taking industrial action together?

Craft unions typically arose among skilled workers seeking to protect and enhance the position their specialized training provided. These workers gained bargaining power from their trade knowledge, limiting the ability of employers to replace unionists and strengthening the ability of workers to move from similar job to similar job. Craft unions were often organized on lines of so-called “business unionism,” which accepted the existence of private property and the capitalist system rather than committing to class warfare, seeking instead to redistribute the gains from capitalism from employers to tradesmen in the form of higher pay, shorter hours, and better conditions. Business unionism practiced by craft or hybrid-craft unions became the basis of the Gompers-era AFL.

Organized labor’s alternative to craft unionism was industrial unionism, under which entire firm’s or local industry’s workforces would organize in a single unit to conduct bargaining and industrial actions such as strikes or boycotts. In its widest form, an industrial union could organize the entire working class against the employing class in “one big union.”

The breadth of industrial unions led their activists and leadership toward broader theories of class struggle, derived from if not necessarily explicitly aligned with those of Karl Marx. This developed into a different characterization of union aims from the workplace focus of business unionism. “Uplift unionism” was the more moderate set of aims, seeking in the words of an early 20th century scholar “to elevate the moral, intellectual, and social life of the worker, to improve the conditions under which he works, to raise his material standards of living, give him a sense of personal worth and dignity, secure for him the leisure for culture, and insure him and his family against the loss of a decent livelihood by reason of unemployment, accident, disease, or old age.” As American labor history proceeded, industrial uplift unionism would come to be more explicitly political and activist than craft-business unionism, leaving its mark less in workplace organizing than on Big Labor’s self-conception as a constituent of a broader liberal-left-progressive movement.

Gompers’s Radical Rivals

Beyond uplift lay “revolutionary unionism,” which sought to mobilize the working class to overthrow the capitalist system to replace it either with socialism or with anarchy. The period from 1890 through 1920 may have seen the strongest position for radical-left politics and activism in the history of the United States, with the Socialist Party and labor organizations associated with Eugene Debs and the later Industrial Workers of the World led by William “Big Bill” Haywood leaving a major mark on American trade unionism, especially the folk memory Big Labor would have of its own history.

Eugene V. Debs began his working life as a railroad worker rising to locomotive fireman in Indiana, but he lost his job in 1874 as the Long Recession of 1873–1879 hit the region. Debs later took a job as a grocery clerk and then was elected an officer in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen. After a rapid rise through the union ranks, Debs began a career in politics, winning election as a Democrat to city office in Terre Haute and to the Indiana state legislature.

After he returned to labor organizing, unsuccessful strikes against the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad in 1888 and against the Pullman Company in 1894 would come to define Debs’s increasingly radical politics. The use of legal injunctions against strikers led Debs to the conclusion that only an industrial union aligned with socialist class struggle could advance workers’ interests. Debs would join the Socialist Party of the United States, standing as its candidate for president multiple times.

In 1905, Debs and other socialist activists thought they had created “one big union” that would organize the working class for struggle to overthrow capitalism. With assistance from the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), a radical labor organization that had helped form previous national unions on the industrial-union model, they formed the Industrial Workers of the World. The WFM had a history of industrial violence—its activists were implicated, though acquitted, in the assassination of a former governor of Idaho—and WFM alumnus William “Big Bill” Haywood would carry that ethic into the IWW, even as Debs departed IWW and organized Haywood’s ouster from the Socialist Party executive.

Haywood and the IWW would, like the Knights of Labor before them, enjoy a meteoric rise and cataclysmic fall. When World War I broke out in 1914, the immediate effects on the U.S. economy led to favorable organizing conditions, including in work the AFL did not think organizable. The IWW’s membership surged into the estimated six figures; radicalism was on the rise.

But when the United States entered the war in April 1917, the “Wobblies” membership of radical rabble-rousers proved its own undoing. Despite Haywood, who was himself opposed to the war on international class-solidarity grounds, seeking to avoid confrontation with a Woodrow Wilson administration extraordinarily hostile to civil liberties, IWW members struck copper mines in the western states leading to confrontations with local authorities. The disputes (and, one must presume, Haywood’s well-known if quietly expressed antiwar sentiments) led to raids on the IWW’s offices and the charging of Haywood and other IWW officials under the constitutionally suspect Espionage Act of 1917. Haywood and his fellows fought the charges and lost. Facing 20 years in federal prison, Haywood defected to the Soviet Union, where he would die in 1928.

Debs too faced Wilson administration persecution during the First World War. Charged and convicted under the Espionage Act, Debs ran his last presidential campaign in 1920 from federal prison. He received over 900,000 popular votes, about 3 percent of total votes cast. In 1921, the new Republican President, Warren Harding, commuted Debs’s sentence to time served and received him at the White House. In ill health, Debs effectively retired from politics and died in 1926.

In the next installment, organized labor overreaches in 1946, and Congress limits union power.