Labor Watch

Creation of the Labor-Progressive Alliance: Why Unions Came to Be

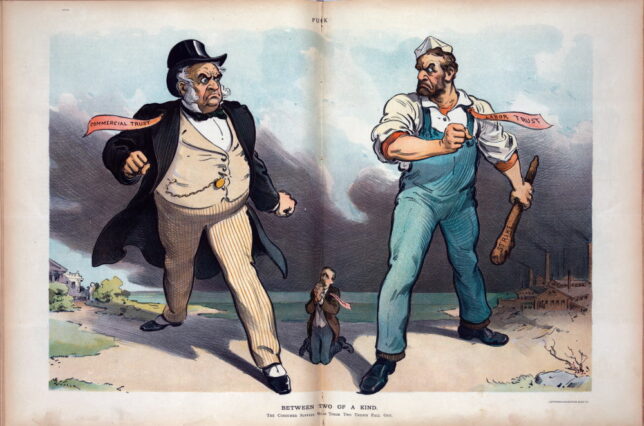

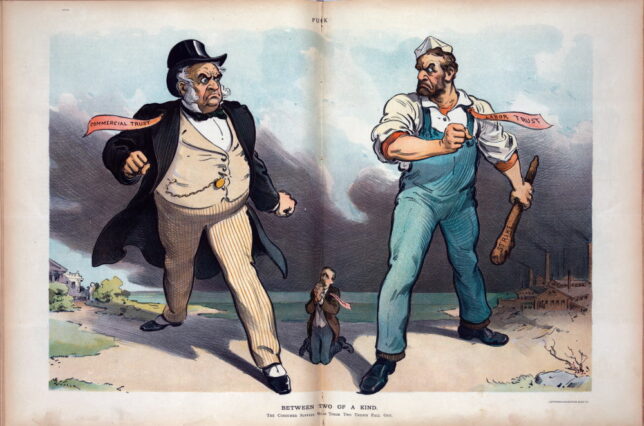

The largest and most influential, such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, became known as “trusts,” combining and colluding to make their owners fantastically wealthy during what became known as the Gilded Age. Smaller industrial firms such as coal mines and garment factories were embroiled in constant competition, while at the mercy of trusts that supplied their raw materials or hauled their products. Credit: Udo J. Keppler. License: https://bit.ly/40zodQp.

The largest and most influential, such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, became known as “trusts,” combining and colluding to make their owners fantastically wealthy during what became known as the Gilded Age. Smaller industrial firms such as coal mines and garment factories were embroiled in constant competition, while at the mercy of trusts that supplied their raw materials or hauled their products. Credit: Udo J. Keppler. License: https://bit.ly/40zodQp.

Creation of the Labor-Progressive Alliance (full series)

Industrialization and Labor Unionism | Why Unions Came to Be

Defining the Workforce | Never Let a Crisis Go to Waste

Why Unions Came to Be: The Condition of American Workers in the Late 19th Century

Labor organization before the Civil War was typically local, short term, and haphazard. Mass industrialization that took off following the end of the conflict drew millions out of farm work and into cities to work in factories and on railroads and to build industrial America.

Those workers found difficult conditions waiting for them. Pay and opportunities to work were inconsistent, surging and falling with the business cycle, with recessionary periods frequent. The 1873–1879 “Long Depression” was the longest recession in post–Civil War history identified by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Daily work hours when work was available were often long, with 12-hour workdays not unthinkable. Economic research suggests 10-hour days were standard by 1880. Industrial accidents causing injury or death were common, and insurance for injured or killed workers was often not available. Child labor and racial discrimination were common. While economic research has cast doubt on the harshest claims of de facto indenture to the “company store,” living and provisioning arrangements run by employers never sat well with a public or workers seeking small-r-republican independence.

Given these difficulties, it is not surprising that working men sought to band together to improve their pay, shorten their hours of work, and ameliorate harsh conditions of labor. In 1869, a secret society of workers known as the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor and modeled on the Freemasons was created. By the early 1880s, in part to satisfy the objections of Roman Catholic clergy who distrusted secret societies, the Knights of Labor lifted their veil of secrecy and became the most prominent labor movement of the age. Led after 1879 by former machinist Terence Powderly, the Knights of Labor had an estimated 700,000 members at its height in 1886.

The most notable cause of early organized labor, including the Knights of Labor, was adoption of an eight-hour standard workday. National campaigns for an eight-hour standard or eight-hour legislation began in the 1860s and continued until the adoption of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938.

Labor struggles during the 19th century were often violent, with ruthlessness from strikers, employers, and the state alike. In May 1886, at least one striker against the McCormick Reaper Works was killed by police. A rally in response to the action and in support of the eight-hour day in Chicago’s Haymarket Square infamously turned violent when a bomb was thrown at police leading to indiscriminate gunfire; the event killed at least seven policemen and four others. The bomb thrower was never identified, but eight men associated with anarchist movements were convicted of murder in relation to the incident on dubious evidence, one of whom was associated with the Knights of Labor. The public relations damage the Haymarket riot did to the Knights proved unsurvivable, and the order declined in influence thereafter.

“Pure and Simple Unionism”: The American Federation of Labor

After the decline of the Knights of Labor in the wake of the Haymarket riot, the leadership of American trade unionism moved to the American Federation of Labor, led for almost 40 years by Samuel Gompers. Born in England to Dutch-Jewish parents, Gompers began work as a boy, ultimately taking a job in a cigarmaker’s shop. In 1863, the family emigrated to the United States, arriving in New York City, where Gompers continued in the cigar-making trade.

Biographers of Gompers dispute how much the budding trade unionist was influenced by Karl Marx and the socialist First International organized in the mid-1860s. Gompers denied having joined the First International, but John H.M. Laslett, a scholar of socialist influences in the early labor movement, noted that Gompers wrote that he read the German socialists including Marx and Friedrich Engels extensively and initially took a broad, proto-industrial-unionist view of organizing the working classes for Marxist class struggle. But while he was influenced by the European socialists, Gompers had little time for theoretical debate or analysis. He focused on establishing trade unions as “purely industrial or economical class organizations with less hours and more wages for their motto” and committing to raising funds to effectively organize strikes and pay members a death benefit.

The American Federation of Labor was organized at a convention of trades unions convened in December 1886. Gompers, then an official in the Cigar Makers International Union, was elected the federation’s president. At the AFL’s founding, he was the union federation’s only full-time officer. Gompers’ authority was quite limited: The AFL’s affiliated unions retained autonomy over their internal operations and organizing, leading one labor historian to write, “His [Gompers’s] position was in modern terms more like that of the Secretary-General of the United Nations than that of the President of the United States.”

In AFL’s early years, socialist movements retained substantial influence, with the Socialist Labor Party–influenced Central Labor Federation in New York City being especially notable. For his part Gompers was involved personally in radical politics, supporting Greenback-Labor presidential candidates in 1876 and 1880 and land-tax advocate Henry George for New York City mayor in 1886. All lost. But by 1893, when Thomas Morgan presented an 11-point socialist program at the AFL convention that included a call for “the collective ownership by the people of all means of production and distribution,” Gompers found himself on the opposite side of the radicals. In 1894, socialist agitation within the union cost Gompers his office for a single one-year term.

Gompers’s leadership and influence over AFL member union was constrained by the federation’s structure. While Gompers insisted that AFL member unions admit Black workers, his ability to enforce his desire was limited. The railroad unions were largely excluded from the AFL on this basis, and the International Association of Machinists was only admitted after it agreed to allow Blacks to join the national membership. However, Gompers was unable to fully integrate the AFL, with some AFL unions (including the Machinists) maintaining segregation in their local unions. By the turn of the 20th century the AFL was chartering segregated city-level labor federations.

Politically, Gompers sought to keep the AFL neutral in partisan terms for much of his leadership of the federation. Yet by the early 20th century his issue-and-politician-specific approach to political intervention, which had been institutionalized in the National Civic Federation aided by U.S. Senator Mark Hanna (R-OH), had given way to alignment with the Democratic Party of President Woodrow Wilson. This alignment was especially clear after the Clayton Antitrust Act formally exempted labor organizations from antitrust laws, which (in theory) limited the use of injunctions to end strikes.

In the next installment, industrial unionism becomes dominant in labor organizing.