Labor Watch

Core Issues in Labor Policy: Independent Contracting

Legendary socialist labor leader Walter Reuther struck against General Motors for control of car prices (control he did not get). Credit: CriticalPast. License: https://bit.ly/3u81FXx.

Legendary socialist labor leader Walter Reuther struck against General Motors for control of car prices (control he did not get). Credit: CriticalPast. License: https://bit.ly/3u81FXx.

Core Issues in Labor Policy (full series)

Every Job a Factory Job | Independent Contracting

Mandating the Closed Shop | Social Justice Unionism

Independent Contracting

Workers are typically classified as one of two types: An independent contractor or an employee.

How Independent Contracting Has Worked. As a general rule, employees have more rights enforceable against the person signing their paycheck than a contractor, but their employers have more power over their work processes and work product. Independent contractors are treated like, well, independent small businesspeople in business for themselves who offer their services to customers who will pay.

Independent contractors, on the other hand, have much more power to direct their own work processes and work product, but they accept more exposure to market forces. As part of that exposure to market forces, they are often free to seek work from multiple work sources at the same time or in rapid succession. They are also not subject to mandatory unionization and collective bargaining.

The common-law test for independent contracting that prevailed nationwide until recently was whether the worker was “free from control and direction in connection with the performance of the service, both under the contract for the performance of service and in fact.”

How Big Labor Wants It to Work. As independent contracting through internet applications (the “gig economy”) has grown in prominence, organized labor has sought to apply its Three-Bigs model to this 21st century work model. And for this, the common-law test is a problem. Application-based workers often contribute their own capital (like a contractor), set their own hours (like a contractor), and work for multiple application platforms, including those in direct competition (like a contractor).

This hurts Big Labor in two ways: First, the application platforms compete with old, Three Bigs–model unionized businesses. This is most visibly the case with rideshare platforms like Uber and Lyft against the unionized taxicabs. Second, contractor status means that application-platform workers cannot be forced to join unions or pay dues, and platforms cannot be compelled to bargain.

So, Big Labor and its allies have devised a way to evade this common-law distinction: The “A-B-C test.” It was most notably enacted through California’s (now substantially revised) AB 5 law. The A-B-C test adds two extra tests to the common-law test, all of which must be satisfied to consider a worker a contractor. They are “the service is performed outside the usual course of the business of the employer,” and the worker “is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, profession, or business of the same nature as that involved in the service.”

The upshot of the A-B-C test is that any contractor using a platform would have to be classified as an employee of the platform because at the very least the platform’s “usual course of the business” is whatever work the worker is using it to facilitate. And once the worker is classified as an employee, he or she is subject to unionization—including by a card-check agreement—with the attendant monopoly bargaining and union dues obligation.

Consequences. After AB 5’s enactment, the repercussions came swiftly: Journalism outlets that had supported AB 5’s adoption cut their California-based paid freelancers. Uber and Lyft announced that without court relief they would have to cease operating in the state.

Fortunately for California workers, legislative relief came: The state’s ruling Democratic Party passed a bill with carve-outs from AB 5 rules for politically connected industries, including freelance journalism, the music industry, and other performing arts. The ridesharing companies pushed a ballot measure, Proposition 22, to comprehensively supersede AB 5’s rules in their industry.

The Biden administration and Congressional Democrats’ PRO Act would explicitly overturn Proposition 22, likely killing application-based work platforms nationwide, putting workers out of work, and taking options from customers. Politically connected industries would clamor for carve-outs, and they would likely get them.

Make Strikes Destructive Again: Undoing 70 Years of Worker and Consumer Protections

In 1945–46, organized labor was at its peak power. The unions had agreed to suspend organized strike action during the Second World War and had (with wildcat exceptions) largely abided by that agreement. But once the war ended, the unions sought to use the extraordinary powers given them by the New Deal.

Empowered by the National Labor Relations Act to compel bargaining, secure that the permanent Democratic majorities that had been elected since 1932 were loyal to them, and lacking any “unfair labor practices” enforceable against them, Big Labor launched the largest wave of industrial action in American history. It sent 10 percent of the workforce (4.6 million workers then, equivalent to 16 million workers now) out on strike. Legendary socialist labor leader Walter Reuther struck against General Motors for control of car prices (control he did not get). Multiple cities were gridlocked by “general strikes” called by labor councils.

The consequences were clear: A recession, always a likely consequence of demobilization, was made worse. Strikes proved so destructive that President Harry Truman—a hardcore union man and New Dealer—had to threaten railroad unions with conscription into the Army if they carried out their threat to strike.

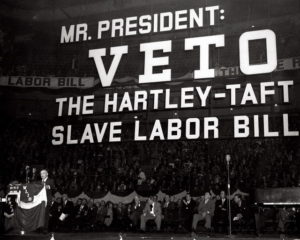

The Taft-Hartley Act placed limits on unions’ strike objectives, established a set of rules that violations of which would be unfair labor practices by unions, and allowed states to ban “closed shops” that required employees to pay dues to a union or lose their jobs. Credit: Kheel Center. License: https://bit.ly/3atLY5j.

The public response was wrath. For the first time since the Great Depression, Republicans took control of both Houses of Congress. With their southern Democratic allies in the “conservative coalition,” the new GOP majorities passed (over Truman’s veto) legislation to curtail the powers organized labor had just shown that it would abuse. The Taft-Hartley Act placed limits on unions’ strike objectives, established a set of rules that violations of which would be unfair labor practices by unions, and allowed states to ban “closed shops” that required employees to pay dues to a union or lose their jobs.

From the moment the bill was enacted, organized labor has sought its repeal, deriding it as the “slave labor law” because it limited organized labor’s legal privileges. And the PRO Act would override two crucial limitations on union power in the law: It would mandate closed shops and the attendant forced dues nationwide, and it would legalize “secondary boycotts,” directly authorizing 1946-style disruptions of national life.

In the next installment, examine the PRO Act’s frontal assault on the right to work.