Organization Trends

Colorado’s Big Blue Political Machine: Rise of the Machine

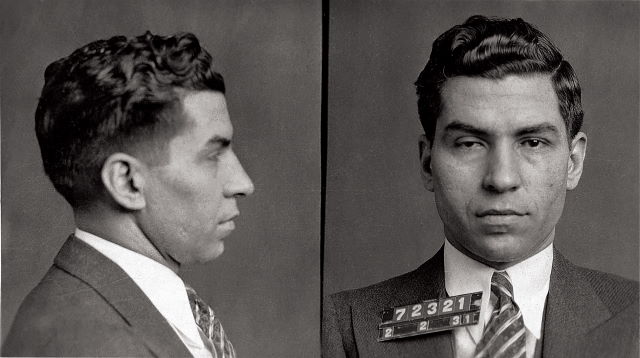

In a hotel suite at the Democratic National Convention, New York City crime boss Charlie “Lucky” Luciano, a provider of financial grease for Tammany, was working to engineer Smith’s nomination. Credit: NYPD. License: Public Domain.

In a hotel suite at the Democratic National Convention, New York City crime boss Charlie “Lucky” Luciano, a provider of financial grease for Tammany, was working to engineer Smith’s nomination. Credit: NYPD. License: Public Domain.

Colorado’s Big Blue Political Machine (full series)

Rise of the Machine | The Gang of Four

The Culture Wars | The Machine Attacks

Summary: In the summer of 2004 four left-leaning Colorado multimillionaires hatched a plot to do the Democrats’ job for them. By the November 2006 election the so-called Gang of Four and the “Roundtable” allies they brought into their orbit had flipped the trifecta to the Democrats and constructed a political infrastructure that has so far prevented Republicans from recovering. This Colorado machine was not in any fashion a direct descendant of the corrupt old political machines: It was not funded or influenced by gangsters or created to financially benefit its multimillionaire creators. In place of the drive for graft, the Colorado cabal pursued leftist ideological and policy goals instead.

Before he became the Democratic presidential nominee in 1932, New York Gov. Franklin Delano Roosevelt had to defeat Democratic rival Al Smith, a former New York governor and member of the notorious Tammany Hall political machine. In a hotel suite at the Democratic National Convention, New York City crime boss Charlie “Lucky” Luciano, a provider of financial grease for Tammany, was working to engineer Smith’s nomination. In another hotel suite, another Tammany delegation, led by yet another New York City underworld leader (Luciano ally Frank Costello) was working for the nomination of Roosevelt.

Traditional political machines such as Tammany were built to seize their corrupt slices of power before candidates were even selected, let alone elected. Real political competition from ambitious politicians was bad for business.

For example, Tammany’s side bet on FDR failed. As president the revered Democrat quickly snapped the party’s 100-plus-year-old connection to Tammany and set in motion the machine’s demise. He even nominally assisted an anti-Tammany Republican’s election as New York City mayor.

Before he became the Democratic presidential nominee in 1932, New York Gov. Franklin Delano Roosevelt had to defeat Democratic rival Al Smith, a former New York governor and member of the notorious Tammany Hall political machine. Credit: FDR Presidential Library & Museum. License: Public domain.

Political machines worked because they often exercised monopoly control over the machinery of government—including the politicians—and divvied up the spoils of that power to their members: contractors, government employees, connected businesses, organized crime, and so forth. Where ambitious politicians can fight among themselves to seize majority power, a political machine has either lost control or does not exist.

Heading into election night 2004, Colorado was a decisively Republican state, with a Republican governor and GOP majorities in both chambers of the legislature. Republican politicians were in control of a “trifecta” monopoly over the three policymaking centers of state government. The Republican monopoly had existed for four of the prior six years.

What happened next is chronicled in The Blueprint: How Democrats Won Colorado and Why Republicans Everywhere Should Care, a 2010 book written by Rob Witwer, a former Republican lawmaker from Colorado, and Adam Schrager, a local political reporter. Ten years later, the lessons from their book continue to be relevant well beyond Colorado.

In the summer of 2004 four left-leaning Colorado multimillionaires hatched a plot to do the Democrats’ job for them. By the November 2006 election the so-called Gang of Four and the “Roundtable” allies they brought into their orbit had flipped the trifecta to the Democrats and constructed a political infrastructure that has so far prevented Republicans from recovering.

When that infrastructure became fully operational in 2006, according to The Blueprint, it turned individual candidates into “simply bit players in their own campaigns” with little control over messages or strategies. Referencing both the victorious Democrat and her vanquished GOP rival in one hotly contested Colorado Senate race, the authors write the candidates “could have taken six-month vacations” and few voters would have noticed.

The politicians had ceased to matter. The Gang of Four had built a modern political machine.

The Rise of the Machine

Mark Twain is credited (though perhaps not accurately) with saying, “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.” The Colorado machine was not in any fashion a direct descendant of the corrupt old political machines: It was not funded or influenced by gangsters, and it was not created from a desire to financially benefit its multimillionaire creators. In place of the drive for graft, the Colorado cabal pursued leftist ideological and policy goals instead.

But while it was built to accomplish very different objectives, the Colorado machine’s biggest gears closely resembled the moving parts that kept old Tammany and its historical cousins in business.

It rhymed.

On election night 2004, slightly more than 1.1 million Colorado voters (almost 52 percent of them) gave the state’s nine electoral votes toward the reelection tally of President George W. Bush. On paper this day should not have marked the decisive beginning of 16 years (and counting) of sustained heartburn for Colorado Republicans.

The last Democratic majority to rule the Colorado House of Representatives had packed its bags 28 years earlier, back when President Jimmy Carter moved into the White House. With a 37-28 GOP majority going into the 2004 campaign, those not in the know could be forgiven for thinking the Republicans would cruise into 2005 still in control of the Colorado House.

But a slim and seemingly improbable 33-32 Democratic majority emerged. The narrow win betrayed what was to become a lasting reversal of fortune. For the next 16 years, through 2020, House Democrats would lose their majority for only two of them.

Similarly, in the Colorado Senate, Democrats had controlled the show for only two of the prior 52 years—dating all the way back to the Kennedy administration. But that rare Democratic majority had been recent, following the 2000 election. Even though Colorado staggers the election of its state senators so not all seats were in play in 2004, the Republicans held just an 18-17 majority.

That too was flipped to an 18-17 Democratic majority. As with the House, it presaged a radically altered future. Through 2020, Senate Republicans would claw back majority status for just four of 16 years.

Then came the gubernatorial election of 2006. Incumbent Republican Gov. Bill Owens could not run for reelection due to term limits. Owens had been reelected in 2002 with a commanding mandate of nearly 63 percent. Another total reversal of fortune ensued: Democrat Bill Ritter won with 57 percent.

The new Democratic governor swept into power with a 39-26 Democratic House majority and a 20-15 Democratic Senate majority.

So, Democrats began January 2007 with a monopoly on policymaking power they had not enjoyed since the Cuban Missile Crisis—and a total reversal of their status from just four years earlier.

But they weren’t running the machine that put them there.

In the next installment of “Colorado’s Big Blue Political Machine,” meet the Gang of Four who built the Colorado political machine.