Labor Watch

Big Labor’s Decline and Left Turn: A Trade Unionist in the White House

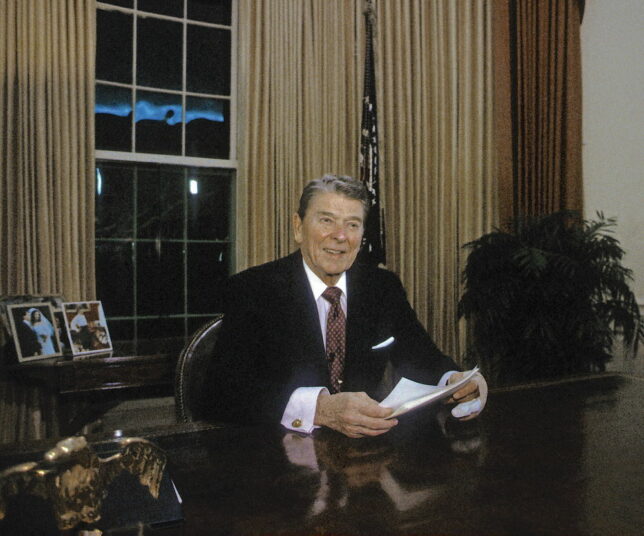

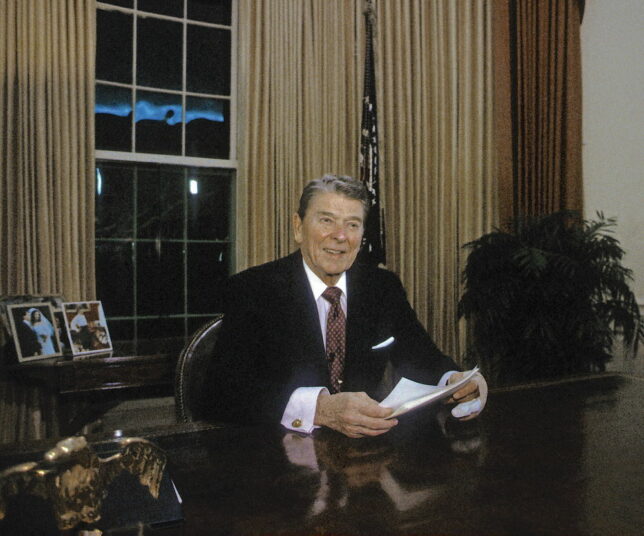

On August 3, 1981, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization precipitated a national crisis. In violation of federal law and the controllers’ employment oaths, the union went on strike, threatening the ability of the civil air transportation system to function. Ronald Reagan’s response would enrage labor unionists, enthrall free-market conservatives, and set the tone for his administration. Credit: mark reinstein. License: Shutterstock.

On August 3, 1981, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization precipitated a national crisis. In violation of federal law and the controllers’ employment oaths, the union went on strike, threatening the ability of the civil air transportation system to function. Ronald Reagan’s response would enrage labor unionists, enthrall free-market conservatives, and set the tone for his administration. Credit: mark reinstein. License: Shutterstock.

Big Labor’s Decline and Left Turn: The Government Workers Rise and Labor’s Center Falls (full series)

A New Power Rises | Labor’s Private-Sector Left | Causes of the Long Decline

A Trade Unionist in the White House | Membership Decline

A Trade Unionist in the White House

Precisely one former national labor union president has been elected to the presidency of the United States. Before his political career, he was already a notable figure, perhaps most notably as the leading actor in the “Brass Bancroft” series of prewar low-budget adventure films and for a supporting role in Knute Rockne: All American. By the late 1940s, he had been elected to lead the Screen Actors Guild (the film-actor predecessor to today’s SAG-AFTRA) and was testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee on his and the union’s efforts to keep the movie industry free from Soviet-aligned Communist control. When his acting career faltered, he became an increasingly prominent and increasingly Republican-aligned political activist, culminating in A Time for Choosing, a speech promoting the doomed 1964 presidential candidacy of Sen. Barry Goldwater (R-AZ).

By 1966, he was a Republican candidate for governor of his home state of California. He would defeat embattled Democratic incumbent Pat Brown by 15 points. In Sacramento, Governor Ronald Reagan was something of a moderate by today’s issue matrix and ideological standards: He signed gun control legislation in response to the Black Panthers’ habit of openly carrying firearms at demonstrations, legislation liberalizing abortion access, and legislation granting certain government worker unions the power to bargain collectively.

By 1976, former Governor Reagan was the standard-bearer for the conservative wing of the national Republican Party, challenging then-President Gerald Ford for the party’s nomination. In 1980, he would win it and ride a national wave to unseat President Jimmy Carter (alongside a GOP majority in the Senate and a “conservative coalition” balance of power in the House) and consolidate the post-Sixties conservative reaction.

Among the organizations that had endorsed Reagan’s presidential campaign was the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO), the labor union for air traffic controllers employed by the Federal Aviation Administration. Upon President Reagan taking office, PATCO expected the usual rewards from government worker collective bargaining; it had, after all, helped elect the boss. Duly enough, President Reagan’s administration offered a substantial pay increase. While Democrats claimed it was a payoff, PATCO demanded more.

And on August 3, 1981, PATCO precipitated a national crisis. In violation of federal law and the controllers’ employment oaths, the union went on strike, threatening the ability of the civil air transportation system to function. Reagan’s response would enrage labor unionists, enthrall free-market conservatives, and set the tone for his administration. Four hours after the strike began, Reagan issued an ultimatum, telling the press:

Let me make one thing plain. I respect the right of workers in the private sector to strike. Indeed, as president of my own union, I led the first strike ever called by that union. I guess I’m maybe the first one to ever hold this office who is a lifetime member of an AFL-CIO union. But we cannot compare labor-management relations in the private sector with government. Government cannot close down the assembly line. It has to provide without interruption the protective services which are government’s reason for being.

. . .

It is for this reason I must tell those who failed to report for duty this morning they are in violation of the law and if they do not report for work within 48 hours, they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated.

The Reagan administration mobilized military personnel, non-unionized supervisors, and strike defectors to keep planes in the air. On deadline day, AFL-CIO head Lane Kirkland joined the picket line. In his diary, President Reagan wrote, “How do they explain approving of law breaking—to say nothing of violation of an oath taken by each [air controller] that he or she would not strike.”

Often in government-worker labor relations both before and after 1981, legal prohibitions on government worker strikes prove toothless if unions test them. Even if government officials facing the strike are not union allies who have no interest in handing out penalties, the public is unlikely to support sanctions ranging from firing to arrest of teachers, cops, and firemen.

But the Reagan administration was prepared for the possibility of having to break a controllers’ strike in a way state governors during the COVID-19 school closures were not. Even before Reagan’s election, the military had begun making contingency plans to keep the civil air traffic network open using military air traffic controllers, nonunion supervisors, and picket-line crossers—one of whose comments was favorably relayed in Reagan’s speech issuing the ultimatum.

These contingency plans were put into effect even before the administration formally fired the strikers on August 5, 1981. That day, Reagan fired 11,000 strikers and laid a ban upon their holding any government job that was not lifted in full until the Clinton administration. The contingency plans worked. A contemporary analysis in the New York Times, published after the Federal Labor Relations Authority formally decertified PATCO, stated, “The controllers were unable to bring a significant halt in the nation’s air travel.”

Expanding on Taft-Hartley: State Laws and Court Cases

While Reagan’s victory had come against a government-worker union, leftists and left-leaning labor historians note the message it sent resounded into the private sector. It signaled that Big Labor was an increasingly paper tiger in the new conservative age, and that the Republican-backed Taft-Hartley Consensus, which focuses on promoting union voluntarism, regulating union conduct, and protecting consumers from labor-dispute fallout, would drive national policy.

Since its creation, the National Right to Work Committee has been the chief proponent of enforcing union voluntarism and protecting the Taft-Hartley Act from various Big Labor and Democratic-backed efforts to restore the full levels of coercion of the original Wagner Act. It survived its narrowest scrape in the mid-1960s, when Democratic supermajorities nearly passed legislation to repeal Section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley Act, the federal provision explicitly authorizing state-level “right to work” laws that forbid conditioning employment on the payment of union fees. A filibuster led by Senate Republican Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) blocked the legislation. The political changes following the failure of the Great Society put that matter to bed for the next half-century.

This win kept state-level right-to-work provisions in force where they could be enacted. As of the 1980s, there were essentially two classes of right-to-work states: the Old South, which adopted right-to-work laws in advance of Taft-Hartley when Florida and Arkansas adopted state constitutional provisions in 1944 and in its immediate aftermath, and right-wing Republican states in the Great Plains and Mountain West.

Beyond those regions, the policy struggled: An attempt to enact a right-to-work law by referendum in California in 1958 failed by a 60-40 margin. With the prospects for a national right-to-work law blocked by consistent Democratic strength in Congress, squeamishness toward the effort by Republicans from union-heavy states like New York and Pennsylvania, and expanding state-level right-to-work beyond its southern heartland unlikely, the Taft-Hartley consensus’s offense moved to the courts and the related but independent National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation.

The foundation (and earlier litigation that was supported by the National Right to Work Committee) secured court precedents short of a national right-to-work principle but that nevertheless constrained Big Labor’s ability to coerce workers, especially for political advocacy purposes. Litigation confined compulsory unionism to the “financial core,” forbidding unions from compelling non-members to engage in union activities other than fee payment. Further litigation culminating in the 1988 Supreme Court decision Communications Workers of America v. Beck limited the amount of compulsory fees to those “necessary to ‘performing the duties of an exclusive representative of the employees in dealing with the employer on labor-management issues.’” In other words, unions could not compel private-sector workers to pay for political advocacy, lobbying, or other expenses not related to collective bargaining.

Government workers won similar protections under the 1986 Chicago Teachers Union v. Hudson decision. Those protections would ultimately be made moot by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation’s win in the 2018 Janus v. AFSCME case, which made the entire government sector functionally right-to-work.

In the next installment, the AFL-CIO played a key role in defeating Soviet Communism, only to be taken over leftist faction in 1995.