Labor Watch

Big Labor’s Decline and Left Turn: A New Power Rises

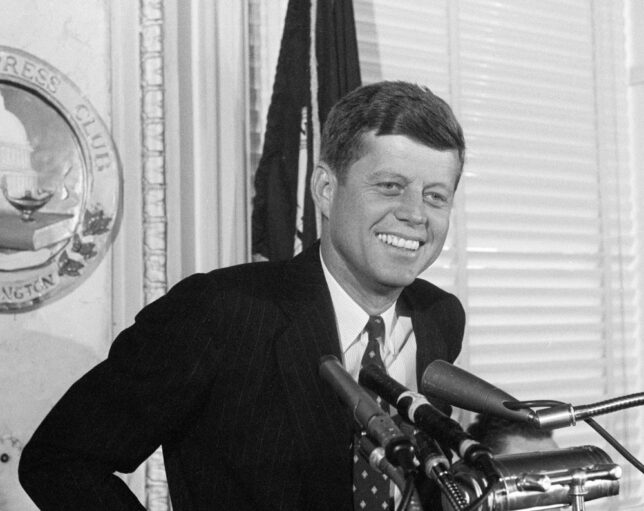

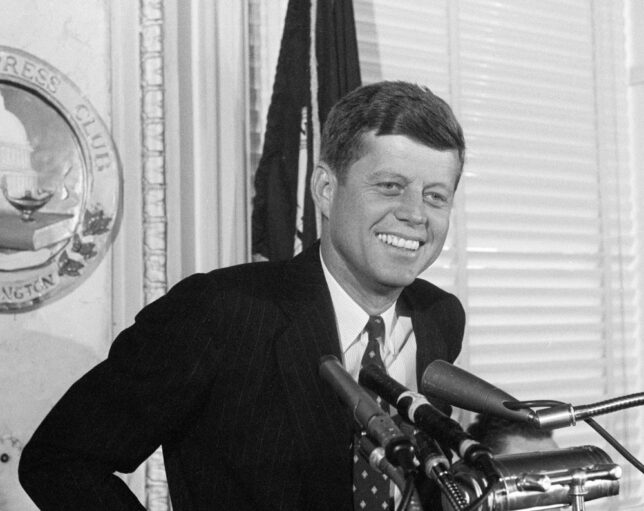

January 20, 1961, was a good day to be an American liberal. John F. Kennedy was taking the oath of office as president of the United States, and Democrats held commanding majorities in both houses of Congress. Public domain.

January 20, 1961, was a good day to be an American liberal. John F. Kennedy was taking the oath of office as president of the United States, and Democrats held commanding majorities in both houses of Congress. Public domain.

Big Labor’s Decline and Left Turn: The Government Workers Rise and Labor’s Center Falls (full series)

A New Power Rises | Labor’s Private-Sector Left | Causes of the Long Decline

A Trade Unionist in the White House | Membership Decline

Summary: As President John F. Kennedy took office in January 1961, organized labor looked ahead toward a future of ever-increasing power and influence. States had begun to advance laws requiring themselves and local governments to bargain with labor unions of government workers. President Kennedy would shortly issue an executive order to bargain with unions in the federal government workforce. The new administration advanced its New Frontier anti-poverty and entitlements-expansion policies that would be expanded after Kennedy’s death by his successor, President Lyndon Johnson, as the War on Poverty and Great Society. And social liberalism supported by organized labor would see advances, especially in civil rights.

American liberalism was at its zenith, and the labor movement was one of its pillars. The AFL-CIO’s George Meany closely aligned with President Johnson. The United Auto Workers’ Walter Reuther became a famed crusader for social democracy and civil rights. But organized labor was already beginning to lose its position in the private-sector workforce, and the changes unleased by the 1960s social-liberal Left would engender a conservative response not seen since Warren Harding’s election on a “return to normalcy” after the Progressive activism of Woodrow Wilson. The changes in organized labor’s composition and the rise of the Sixties Radicals in left-wing activism would fundamentally change the American union movement in the succeeding era and contribute to the coming Long Decline in organized labor’s membership position and political influence.

By the 1980s, conservatives were in the political ascendancy, and the center-left New Deal-Cold War consensus among labor unionists was on its way out. Lane Kirkland, Meany’s successor at the AFL-CIO, led its last stand, fighting against the Reagan administration’s domestic policies while supporting the anti-Soviet free trade unions of Eastern Europe like Poland’s Solidarność. When the Eastern Europeans prevailed and the Soviet Bloc fell, New Deal–era American trade unionism fell with it. In its place would rise today’s contemporary woke-socialist labor movement focused on government workers and led by a card-carrying Democratic Socialist.

January 20, 1961, was a good day to be an American liberal. John F. Kennedy was taking the oath of office as president of the United States, and Democrats held commanding majorities in both houses of Congress. For organized labor, a key pillar of the mid-century liberal-Democratic coalition, the union-skeptical Eisenhower administration was out, and a friendly Kennedy administration was in. Big Labor even dared to hope that the Kennedy administration would end the 14-year Taft-Hartley experiment of subjecting its operations to government scrutiny and regulation.

Kennedy’s administration and the administration of his successor Lyndon Johnson would be the apogee of 20th-century liberalism. Major legislation promoting Black Americans’ civil and voting rights, expanding government provision of health care, regulating air quality, and commissioning numerous other expansions of the national government in what would come to be known as the Great Society and the War on Poverty advanced, most with the backing of Big Labor. At all levels of government, collective bargaining was expanded to more government workers, building up the numbers of labor unionists.

But the winds of change would not be in Big Labor’s favor for long. Alongside the apogee of mainline liberalism came the genesis of a radical New Left—a genesis Big Labor midwifed.

Walter Reuther, the United Auto Workers leader who personified Kennedy-Johnson era liberalism, provided financial support to the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) from his union. SDS generated the Port Huron Statement, a declaration of left-wing principles and programs credited with launching the New Left. Over the decade, SDS would evolve from a left-wing, pro-union student activism center into a radical-left, arguably outright Communist faction that would devolve into the Weather Underground, a radical-left terrorist faction, by the 1970s.

The rise of the New Left and its radical positions on foreign affairs (affirming neutrality when not openly siding with Soviet Communism) and social policy (best summarized as “acid, amnesty, and abortion”—a liberal’s description of Sen. George McGovern’s 1972 presidential platform) provoked first right-populist and later conservative reactions. This curtailed Big Labor’s political ascendancy, which had seen efforts to repeal the Taft-Hartley Act’s authorization of state right-to-work laws fall to a Senate filibuster in 1965.

Changes in the world and national economies also ended Big Labor’s economic ascendancy. Abroad, the revitalization of the Western European and Japanese economies as they rebuilt from World War II generated international competition that challenged sclerotic, unionized American companies such as the Detroit Three automakers. Domestically, air conditioning, which became widespread in the 1960s and 1970s, made living and working in the right-to-work South more bearable. Legislation endorsed by Big Labor, on issues from civil rights to Social Security to the standard eight-hour workday, also reduced the demand for private-sector union membership. And the damage done to Big Labor’s standing by labor racketeers and Communist domination cannot be overstated.

Thus, as the era proceeded, labor’s left wing was strengthened by the rise of government worker unionism, but the labor movement itself fell into its long decline. While Lane Kirkland, who succeeded George Meany as head of the AFL-CIO in 1979, spent heavily on foreign labor movements opposed to Communism, socialism rose in his own movement. After the Berlin Wall fell, it would strike, empowered not only by foreign affairs but also by a shifting balance of power in Big Labor itself.

At the outset of Kirkland’s tenure, the proportion of private-sector workers who were union members was slightly more than one in five. By the time he left office as Big Labor’s left turn was about to begin in 1995, the proportion was less than one in nine. Meanwhile, government worker unionism remained strong, with a consistent four in eleven government workers being union members throughout the period. This relative ascendancy of government unions against private-sector unions would culminate in the rise of a man reported to carry a membership card in the Democratic Socialists of America to Meany’s old office, ushering in the contemporary era of full-spectrum-leftist Big Labor.

A New Power Rises: Government Worker Bargaining

Prior to the late 1950s, the concept of collective bargaining among government workers was extremely controversial. In 1919, conservative Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge (R) had risen to national prominence by cracking down on a strike by Boston policemen. He wrote a telegram to Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor (which had chartered the Boston Police Union), stating, “The right of the police of Boston to affiliate has always been questioned, never granted, is now prohibited.” Governor Coolidge further wrote, “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.” President Woodrow Wilson, a staunch progressive who had helped bind organized labor to his Democratic Party, also denounced the strike, saying, “I want to say this, that the strike of policemen of a great city, leaving that city at the mercy of an army of thugs, is a crime against civilization.”

Even through the Depression era and the expansions of organized labor’s power that were enacted in that period, political figures supportive of private-sector organizing expressed skepticism that collective bargaining was appropriate for civil servants. President Franklin Roosevelt, who had signed the Wagner Act that established the private-sector labor-relations regime, wrote to the National Federation of Federal Employees:

All Government employees should realize that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service. It has its distinct and insurmountable limitations when applied to public personnel management. The very nature and purposes of Government make it impossible for administrative officials to represent fully or to bind the employer in mutual discussions with Government employee organizations. The employer is the whole people, who speak by means of laws enacted by their representatives in Congress.

Even as late as 1959, the AFL-CIO executive council resolved that “government workers have no right [to collectively bargain] beyond the authority to petition Congress—a right available to every citizen.” But even as that resolution was adopted, the landscape of government worker associations was changing. New York City and the state of Wisconsin were granting government worker unions collective bargaining powers, and President Kennedy would extend limited collective bargaining to the federal sector in 1962 under Executive Order 10988. By the end of the decade, many more states had extended collective bargaining powers to their government worker unions; this list notably included California, in which Governor Ronald Reagan (R) had signed the Meyers-Milias-Brown Act that gave unions and local governments power “to reach binding agreements on wages, hours, and working conditions.”

As the 1970s concluded, approximately 37 percent of government workers were union members, and a further 8 percent were covered by union contracts (with many of those “covered” workers required to pay compulsory union fees as a condition of their employment), according to the historical Union Membership and Coverage Database published by Barry Hirsch, David Macpherson, and William Even. As the government worker unions grew and the private-sector unions shrank relative to one another, the power balance in the labor movement shifted from the New Deal/Great Society welfare statism of the private-sector unionists to the often-explicit socialism of workers who relied on Big Government for their paychecks and the former Sixties Radical activists who led them.

In the next installment, in the 1960s the strength of the union Left was in the private sector.