Labor Watch

In Defense of Taft-Hartley: Why Taft-Hartley Came to Be

While strikes and lockouts from the 1940s through the 1970s often took over 1 million Americans out of work, the 21st century has not yet seen a year with half a million idled and the attendant fallouts in the broader economy. Credit: Amber Loera. License: Shutterstock.

While strikes and lockouts from the 1940s through the 1970s often took over 1 million Americans out of work, the 21st century has not yet seen a year with half a million idled and the attendant fallouts in the broader economy. Credit: Amber Loera. License: Shutterstock.

In Defense of Taft-Hartley (full series)

Why Taft-Hartley Came to Be | The Taft-Hartley Consensus

Advancing Voluntarism | Protecting the Public

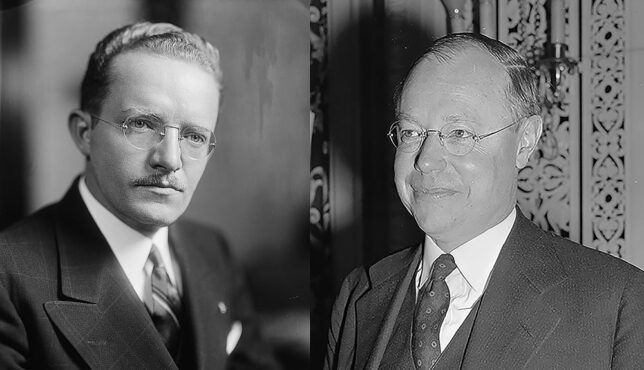

In 1947, organized labor reaped the whirlwind from the massive disruptions it inflicted on the American economy in 1945–46. Sen. Robert A. Taft (R-OH) shepherded passage of the Labor Management Relations Act, which curtailed many of the powers given to Big Labor by the National Labor Relations Act. The Labor Management Relations Act, better known as the “Taft-Hartley Act” after its sponsors, Sen. Taft and U.S. Rep. Fred Hartley (R-NJ), advanced three principles that have come to define the conservative approach to labor relations in the decades since: voluntarism in union membership and activities, government scrutiny of labor union operations, and protection of the public from the fallout from labor disputes. Advancing those principles has aided the American economy and the conservative political movement, to the point that some believe they can be laid aside. A close examination, however, demonstrates clearly that continuing on the Taft-Hartley-inspired course is the prudent course and that expanding union power in the name of conservatism would be a political and economic blunder.

Seventy-six years ago, the most effective federal conservative legislator of the 20th century achieved his greatest victory. Sen. Robert A. Taft (R-OH) is better known in presidential folk-history memory as the noninterventionist primary opponent to President Dwight Eisenhower in 1952. But five years earlier, Taft led the Republican legislative majorities that swept to power in the 1946 midterm landslide to pass the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 over President Harry Truman’s veto. The act significantly curtailed union power in response to union abuses in the immediate post–World War II period.

Since then, the principles underlying what is widely known as the Taft-Hartley Act (after “Mr. Republican” and his House co-sponsor, Rep. Fred Hartley (R-NJ)) have animated a consensus for conservative labor-relations policy. Operating within the framework established by New Deal liberals during the Depression, Taft-Hartley conservatives pushed to restore voluntarism to union membership and union activities, to subject union activities to government scrutiny warranted by the special powers that the federal government had given organized labor, and to protect consumers and the broader economy from the fallout from labor disputes.

Seven and a half decades later, rising factions of intellectual conservatives propose to throw out these consensus principles. Whether inspired by left-wing foundation money or by spelunking in 19th-century Catholicism, these “new right” thinkers propose empowering coercion by organized labor, enabling unions to harvest dues from more unwilling “members” and to subject more unwilling workers to their social and economic agendas in the workplace. This would also leave consumers and the public at the mercy of activist groups that form a foundational pillar of the left-wing infrastructure.

That such a faction could rise is a testament to the Taft-Hartley consensus: It achieved its goals so thoroughly that conservatives themselves forgot why they need it. Especially after the Janus v. AFSCME decision made the entire government sector functionally right-to-work, fewer conservatives than ever are compelled to pay union fees to hold their jobs. Since the George W. Bush administration expanded union disclosures, organized labor’s spending on political agendas and official perks have faced the public scrutiny they deserve. With rare exceptions that illustrate the need for further Taft-Hartley consensus policies, the public can go through life blissfully unaware of and unaffected by the private disputes of other people’s employers and employees.

But with the Biden administration committed to advancing social justice unionism as part of a broad left-wing front, the Taft-Hartley right-of-center policy consensus may be more necessary today than it has been in decades. Abandoning it for nothing would be foolish.

The principles underlying what is widely known as the Taft-Hartley Act (named after Sen. Robert A. Taft [R-OH] and his House co-sponsor, Rep. Fred Hartley [R-NJ]) have animated a consensus for conservative labor-relations policy. Credit: Harris & Ewing. License: loc.gov.

Before assessing the success and continued benefits of the Taft-Hartley approach, it is worth exploring the history of how the Taft-Hartley Act and the right-of-center policy consensus it fostered came to be.

Some reasons date to long before the New Deal and the progressive-left political-economic regime it created. Consider the long-standing political orientation of organized labor itself. While Republicans such as Sen. Mark Hanna (R-OH), a close ally of President William McKinley, made some efforts to court craft unions around the turn of the 20th century, unions found more receptive ears among populist-progressive Democrats, who commanded blocs of class-conscious urban immigrant and second-generation voters, than Republicans aligned with and funded by the rising industrialist class and backed by entrepreneurial-minded homesteaders.

The courtship between Big Labor and Big Government advanced through the passage of legislation during the Woodrow Wilson administration that exempted organized labor from antitrust laws. The passage of the Wagner Act in 1935—which compelled businesses to bargain with majority unions on the basis of one majority union solely empowered to establish a contract for all workers—consummated the marriage. Much of the subsequent New Deal legislation simply nationalized long-standing union aims as government policy, including old-age pensions, a standard eight-hour workday, and a national minimum wage. The third of the Three Bigs, Big Business, largely conceded to Big Labor and Big Government in this era.

But the imbalance of power the Wagner Act created between Big Labor and other economic actors would not be made apparent until after the Second World War. With the major industrial organization campaigns—most prominently the United Auto Workers’ campaigns to unionize the Big Three Detroit automakers—essentially completed and the wartime pacts to prevent disruptions to war production from labor disputes lapsed, whether the Wagner Act had brought “labor peace” was put to the test in 1945 and 1946.

It hadn’t. Instead, with war’s end came the end of labor peace: the largest strike wave in American history. Almost 10 percent of the workforce (4.6 million workers then, equivalent to 16 million people today) went on strike. The economic and social damage got so bad that even New Dealers had enough. President Truman, responding to a strike by railway men, denounced the act in a national radio address in no uncertain terms: “I come before the American people tonight at a time of great crisis. The crisis of Pearl Harbor was the result of action by a foreign enemy. The crisis tonight is caused by a group of men within our own country who place their private interests above the welfare of the nation.”

President Truman continued, describing the damage the strike was doing to the country:

The effects of the rail tie-up were felt immediately by industry. Lack of fuel, raw materials and shipping is bringing about the shutdown of hundreds of factories. Lack of transportation facilities will bring chaos to food distribution.

Farmers cannot move food to markets. All of you will see your food supplies dwindle, your health and safety endangered, your streets darkened, your transportation facilities broken down.

The housing program is being given a severe setback by the interruption of shipment of materials.

Utilities must begin conservation of fuel immediately.

Returning veterans will not be able to get home.

Millions of workers will be thrown out of their jobs.

And then, the self-proclaimed “friend of labor” issued an ultimatum:

If sufficient workers to operate the trains have not returned by 4 p.m. tomorrow, as head of your government I have no alternative but to operate the trains by using every means within my power. I shall call upon the Army to assist the Office of Defense Transportation in operating the trains and I shall ask our armed forces to furnish protection to every man who heeds the call of his country in this hour of need.

The striking unions capitulated to Truman the following day, even as Truman was addressing Congress on the strike. The railroad strike was merely the most disruptive of the disputes that exacerbated economic strife from demobilization. The economic and social consequences led to a Republican sweep in the 1946 midterm elections.

Job one for the new Republican majorities was passing legislation to ensure the 1945–46 economic and social disruption would never happen again and to achieve the objective of “labor peace” the Wagner Act had set for itself and failed to bring. They would receive cross-party backing from southern Democrats more skeptical of organized labor than their Yankee co-partisans, which gave the “conservative coalition” the numbers to override President Truman’s cynical veto.

In the next installment, the Taft-Hartley conservative consensus rest on three principles.