Labor Watch

A Mandate for Labor Error: Coming to Policy at Last

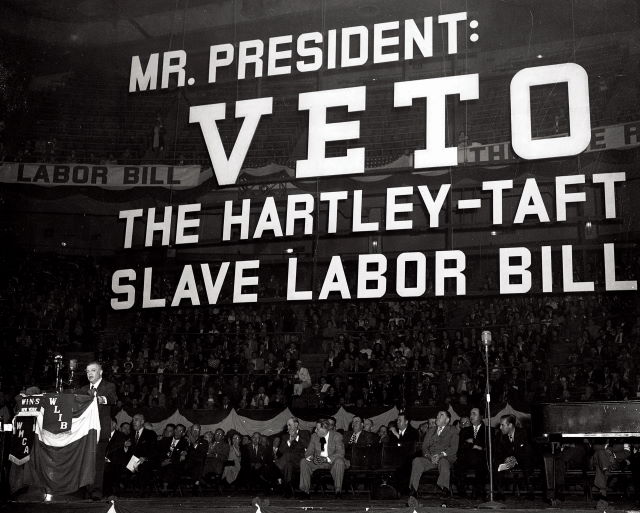

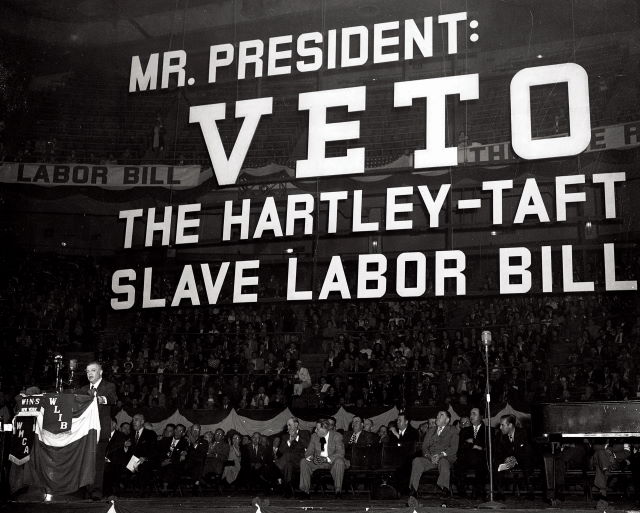

The Taft-Hartley Act placed limits on unions’ strike objectives, established a set of rules that violations of which would be unfair labor practices by unions, and allowed states to ban “closed shops” that required employees to pay dues to a union or lose their jobs. Credit: Kheel Center. License: https://bit.ly/3atLY5j.

The Taft-Hartley Act placed limits on unions’ strike objectives, established a set of rules that violations of which would be unfair labor practices by unions, and allowed states to ban “closed shops” that required employees to pay dues to a union or lose their jobs. Credit: Kheel Center. License: https://bit.ly/3atLY5j.

A Mandate for Labor Error

Statism from the Right | Big Labor Radicalizes

Strange Bedfellows | Coming to Policy at Last | Conclusion

Coming to Policy at Last

Having considered the history of conservative labor-relations policy, the Sirens calling some conservatives away from that historically grounded approach, and the strange bedfellows funding key contributors to Project 2025’s direction for labor policies, we now turn to the policies themselves.

Importantly, Project 2025 did not fully abandon the policies of the Taft-Hartley consensus. The document rejects the Biden administration–Big Labor approach to expanding union power and membership as espoused in the Richard L. Trumka Protecting the Right to Organize Act (H.R. 20/S. 567) and the administration’s regulatory program. For example, unions and their allies seek to redefine joint employment so as to make national branding companies (e.g., McDonald’s) liable for the mistakes of independent franchises, to restrict independent contracting relationships, and to greatly assist union organizing by allowing unions to bypass secret-ballot elections and substitute “card checks.” Card checks enable union organizers to pressure workers to sign cards of approval. All these tactics would make it easier for unions to involuntarily unionize larger portions of the American workforce.

In contrast, the Mandate’s recommendations reject these union-sought policies and uphold principles of voluntary union membership by preventing unions from coercing new workers into dues-paid membership.

The document also carries forward the Taft-Hartley consensus view of labor union supervision when it calls upon the next administration to adopt regulations that will expand required financial disclosures to include union-controlled “trusts” and intermediate bodies, as the Trump administration proposed.

But driven by ideological incoherence perhaps generated by the “help” of American Compass’s Cass, the chapter makes two grave errors. The first is a clear violation of the Taft-Hartley consensus principle of union voluntarism: The document fails to condemn “project labor agreements” or call for repeal of the federal Davis-Bacon Act, which largely requires them. Instead, it relegates criticism of project labor agreements to an “alternative view.” In a Twitter thread hailing his influence over what would be conservative labor policy, Cass praised the chapter’s defense of Davis-Bacon.

Project labor agreements grant privileges to unionized contractors in government projects by setting “prevailing wage” levels at the union rate. This disadvantages “merit shop” contractors who are non-union, even though the “merit shop” industry is a key supporter of the conservative movement and the Republican Party that gives it political force. Its leading trade group, the Associated Builders and Contractors, is almost exclusively a supporter of Republican candidates.

But the worst proposal in Mandate does not merely leave a bad policy alone. It recommends adopting a policy imported from the European social democracies that will, despite its being advertised as “non-union worker voice and representation,” empower the labor unions that fund Democratic campaigns and liberal advocacy.

Specifically, Project 2025 proposes adopting Sen. Rubio’s TEAM Act from the previous Congress. When it was introduced, I characterized the legislation as “a misguided Republican gift to Big Labor,” and so it remains. The TEAM Act would allow the creation of “employee involvement organizations” (EIOs) modeled on continental Europe’s works councils, which are collective forums that petition employers on working conditions, are informed of proposed changes to working procedures, and engage in formal labor-management dispute resolution.

While the TEAM Act’s organizations would start out as optional at the employer level (thus arguably not violating the Taft-Hartley consensus principle of voluntarism), it would be extraordinary if they stayed that way. Germany’s works council system may be the prototype works council system in the developed industrial world: Its councils, governed by the 1972 Works Constitution Act passed under the government of Social Democratic Chancellor Willy Brandt, are very much not voluntary. If workers petition for one, it must be created and administered pursuant to the act. Its membership is elected, and the trade unions that exist parallel to the works council have the right to nominate candidates for the council.

If the TEAM Act is adopted, it is easy to imagine a future administration that more openly supports Big Labor enacting German-style changes to increase the power of unions within the employee involvement organizations. On that day, a conservative writer who backed an EIO for protection from ideological censorship might find his works council governed by a majority from the NewsGuild, which has a history of campaigning for radical-left ideological purity in the workplace in the name of “safety.” The conservative would not be protected from woke ideological fads enforced by union activists.

The TEAM Act contains an even more troubling proposal than its works council provision. For years, liberal politicians have sought to meddle with the composition of corporate governing boards, usually on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) grounds. But some pols have endorsed another European import—the union representative on the corporate board. And so does the TEAM Act.

Of course, TEAM Act’s supporters don’t call it a “union” representative. Instead, they call it a “worker” representative chosen by the works council/employee involvement organization. But as with works councils themselves, a cursory review of the European experience shows that these representatives are frequently if not nearly exclusively union-affiliated. American labor observers should recall the United Auto Workers’ various unsuccessful campaigns to create a works council–inspired labor union arrangement with Volkswagen in Tennessee. What was a driving force behind the company’s self-emasculating neutrality toward those efforts to boost union power? IG Metall, the social-democratic German labor union allied with the American-liberal UAW, which holds a “worker” seat on Volkswagen’s board in Germany.

At non-union companies with an EIO, the offer of even a nonvoting board seat would create additional incentives for union “salting,” the practice of securing employment for union activists who then conduct organizing from within a company. When TEAM was first proposed, populist Washington Post columnist Henry Olsen praised the powers that even the nonvoting board representative would have:

Groups formed in larger businesses gain an additional advantage for their workers: a seat on the corporation’s board of directors. Although that worker-director would be nonvoting, the company would have to share with them all information provided to voting directors. Knowledge is power, and access to it would likely improve workers’ leverage within the corporate structure.

A union organizer would love to exploit that information to conduct both traditional shop-floor organizing and coercive “corporate campaigns” that target businesses’ names and public reputations. The TEAM Act would help the organizer obtain it. Thus, the TEAM Act could lead to more Republican workers forced to pay union dues to labor unions that fund transgender activism, abortion advocacy, and DEI programming.

The American Compass types who think that their views should control labor-relations policy in a future Republican presidency hope to fundamentally break the Taft-Hartley consensus. Ostensibly to empower workers, they would also break a corporate-management precedent that liberal activists across policy issues have sought to break, and in doing so they would almost certainly open the door to organized labor’s left-wing cadres, who will pay no heed to conservative workers’ views.

In the next installment, strengthening unions will not improve workers’ lot or protect them from woke fads.