Labor Watch

The Turn at the Millennium: Why Big Labor Switched Sides on Immigration

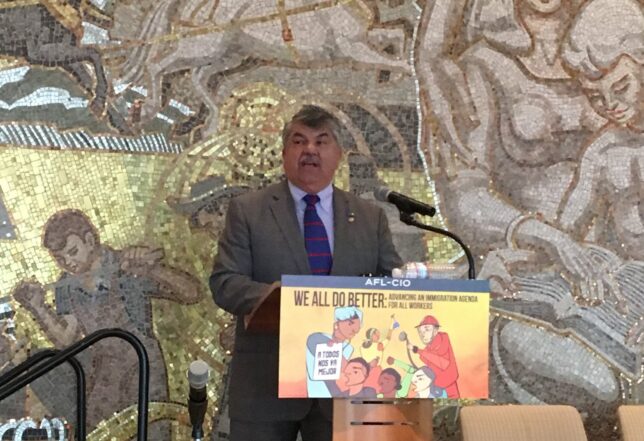

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka speaking at a pro-immigrant worker event in May 2018. Credit: AFL-CIO.

AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka speaking at a pro-immigrant worker event in May 2018. Credit: AFL-CIO.

In 2000, the executive council of the AFL-CIO made what union-activist publication Labor Notes called “a dramatic reversal of its past policy” on immigration. In Labor Notes’ words, the council called “for an immediate amnesty for undocumented immigrants, and an end to sanctions on employers who hire them.”

This statement represented a turn for American organized labor, which had mostly supported immigration control since its prehistory. In the ensuing two and a half decades, organized labor completed its flip-flop to support for a broad amnesty for illegal immigrants and liberal expansionist immigration reforms. Since the reversal, presaged by the federation’s resistance to strict immigration-restriction proposals in the 1990s, Big Labor has been a staunch ally of both Everything Leftist identity-based immigration activists and business lobbies like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. This raises the question: Why?

The Old Ways

Logically, one would think organized labor would make a simple labor market calculation. If labor supply is decreased, wages and fringe benefits should rise, and unions should have more cartel control of the labor supply. Unionism on the American model is based on union bosses holding cartel control of the labor supply, which is why, even in right-to-work states that forbid compulsory payment of union fees, unions seek to subject all workers to the union contract, a practice known as exclusive monopoly bargaining.

Until the 1990s, most prominent leaders in organized labor were united in making the labor-market calculation, though a minority of unionists pushed for cross-nationality solidarity. Some of the first “union labels” were promoted by “white labor leagues” in early California, which affirmed that the products had not been made by Asian immigrants (mostly from China). Legendary American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers, himself an immigrant to the United States, was skeptical if conflicted on the issue of European immigration and adamantly opposed (often in plainly racist terms) to Asian immigration. His AFL backed the harshly restrictionist Immigration Act of 1924, which closed the “Golden Door” from Europe and affirmed closure of migration to Asians for the next four decades.

Gompers was hardly alone. A. Philip Randolph, head of the Pullman porters’ union and the most prominent Black trade unionist of the early 20th century, wrote an editorial in a Black community newspaper calling for an immigration moratorium amid debate over the 1924 Act. Cesar Chavez, the farm labor organizer who founded the United Farm Workers of America, was a militant opponent of illegal immigration.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, while the labor movement backed the ending of national origin quotas under the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, unions still sought some method to enforce immigration laws against employers. Employer-based enforcement appealed to labor-liberals of the late 20th century, since it was thought that the pain of raids would fall on the business community and ethnic minority civil rights would be better protected than under a regime of enforcement against individual illegal immigrants. In 1986, the Simpson-Mazzoli Act enacted an employer-level enforcement regime in exchange for granting legal status to millions of previously illegal immigrants, moves that organized labor supported.

Behind the Turn

Simpson-Mazzoli was not successful in deterring or restraining illegal border crossing. By the 1990s, Congress had convened a bipartisan commission to study potential immigration policy changes. The commission recommended tightening caps on immigrant admissions, a reorganization of immigration enforcement in the federal government, and a substantial program of “Americanization” to promote shared values. The AFL-CIO opposed the legislative package that sought to codify the commission’s restrictionist recommendations in law, part of a trend through the 1990s that the late Cornell Industrial and Labor Relations School professor Vernon Briggs, a trade union-friendly academic who sat on the board of the ideologically heterodox, single-issue immigration-restrictionist Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), identified as marking the transition that would lead to the full turn at the millennium.

Four major undercurrents were driving organized labor’s turn from restrictionist (or moderate) on immigration to effectively anti-anti-open borders. By 2013, the left-wing magazine The New Republic wrote that “No group in America, aside from Latino activists, is a more steadfast champion of generous immigration reform than organized labor.”

First, there was a subtle change in the dominant ideology within organized labor from mid-century liberalism toward contemporary Everything Leftism. The Cold Warriors and crooks who led Big Labor when Big Labor was at its biggest were on their way out by the 1990s. The new breed of senior union organizer got their starts in Students for a Democratic Society and other 1960s-radical organizations. Many would later work diligently in Alinsky-style community organizing through groups like ACORN and People Organized to Win Employment Rights. As those groups matured, these activists saw the organizing group absorbed into a conventional union or found themselves taking jobs in traditional Big Labor.

By the mid-1990s, these activists were reaching the top of Big Labor’s greasy pole and looking to shift the declining labor movement to the left by making alliances with environmentalist, racial and ethnic-interest, and socially liberal groups. Social justice unionism overcame the simple labor-market calculations and cartel-organizing logic of their predecessors when Big Labor sided with the ethnic-interest Left for expansionist immigration.

Second, immigrant workers both legally present and illegally present provided organizing opportunities for the Alinskyite community and ethnic-interest groups and their labor union allies. The old union organizer’s proverb goes, “The best union organizer is a bad boss,” and a common feature of underground illegal-immigrant employment is callous disregard for labor laws. Biden Acting Labor Secretary Julie Su won a fellowship from the left-wing MacArthur Foundation for her work organizing immigrant workers enduring highly unpleasant conditions in the garment industry in Los Angeles.

This served the ideological interests of the new labor activists as well. As Su’s writings on critical race theory demonstrate, exploited illegal-immigrant (or mixed-status immigrant) workers were to the broader Left a rich vein of potential union members whom unions led by radical cadres could turn into activists for broader left-wing interests.

Third, and prominently stated at the time the turn happened, was dissatisfaction with the implementation of Simpson-Mazzoli’s employer sanctions. Union officials alleged that employers were using the threat of handing immigrant (especially illegal-immigrant) workers over to immigration authorities as a stick to hold workers in substandard conditions in line. Tom Palley, an AFL-CIO economist, said in a 2001 debate with CIS’s Briggs:

We need to take away employers’ ability to exploit this pool of workers. That involves, among other things, legalization, possibly trying to give safe harbor to undocumented workers where they are employed in for employer violations of labor law. So if you’re trying to form a union and the employer brings up the INS and says, you’re an undocumented worker, you’ve got to give that undocumented worker safe harbor. That is the type of thinking that is behind the AFL-CIO’s policy.

If concerns about enforcement burdens were the stated reason for the shift in Big Labor’s immigration program, the unstated reason came out in book form two years later from two labor-friendly but not union-affiliated commentators. The Emerging Democratic Majority, written by John Judis, then of The New Republic, and Ruy Teixeira, then of the Century Foundation, proposed that politics in the first decades of the 21st century would be defined by a liberal coalition of working-class voters, single women, urban professionals, and immigrant communities.

For a labor union movement declining in power and prestige from economic forces and workers’ choices as the conservative Taft-Hartley consensus grew in authority, liberal politicians riding immigrants’ votes and the votes of sympathetic urban professionals to power could drive the policy changes that could “RETVRN” American labor-employment relations to the 1940s. That these political incentives aligned with Big Labor’s rising ideological tendencies was simply a bonus.

Consequences of the Turn

The consequences of the turn are far greater than just a trail of befuddled populist-nationalists and their allies in the ideologically heterodox world of specialized anti-immigration groups (like CIS) who cannot understand why organized labor rejected its historic labor-market-based analysis of the immigration issue. Leftist organizing groups with ties to immigrant communities gained influence within and alongside Big Labor. Within Big Labor itself, the unions most interested in liberalizing immigration like the SEIU, the United Food and Commercial Workers, and Unite Here gained influence.

Taken in the broader context, Big Labor’s turn at the millennium on immigration is an important marker of the rise of social justice unionism, perhaps as important as the election of John Sweeney, who midwifed the turn, as president of the AFL-CIO. Likewise, the shift and the way it is remembered on the left, as a triumph of progressive mutual interest over mere “business unionism” and self-interest, reveals the extent to which even radical leftism is baked within organized labor’s story of itself.