Organization Trends

The Thesis That Drove American Politics Crazy: The Emerging Democratic Majority

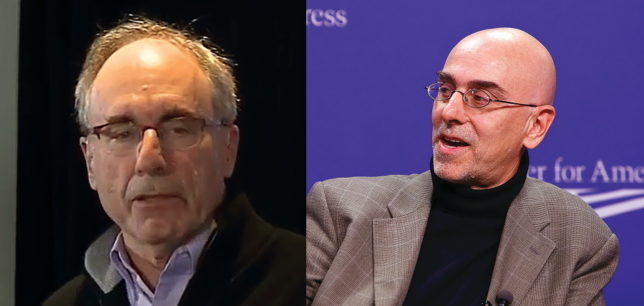

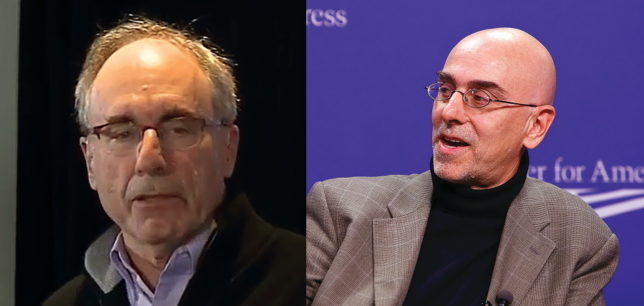

In their imaginatively named The Emerging Democratic Majority, John Judis (left) and Ruy Teixeira (right) argued that the country was on the cusp of transition from an industrial economy focused on suburban-urban and black-white divides with residual Protestant values to a postindustrial economy focused on “ideopolises” with secular-progressive values and a commitment to racial equality. (Judis) Credit: C-SPAN. License: https://bit.ly/3A9YxiX. (Teixeira) Credit: Center for American Progress. License: https://bit.ly/3Qfm0Vt.

In their imaginatively named The Emerging Democratic Majority, John Judis (left) and Ruy Teixeira (right) argued that the country was on the cusp of transition from an industrial economy focused on suburban-urban and black-white divides with residual Protestant values to a postindustrial economy focused on “ideopolises” with secular-progressive values and a commitment to racial equality. (Judis) Credit: C-SPAN. License: https://bit.ly/3A9YxiX. (Teixeira) Credit: Center for American Progress. License: https://bit.ly/3Qfm0Vt.

The Thesis That Drove American Politics Crazy (full series)

The Emerging Democratic Majority | A Prescription or a Prophecy?

From McConnell to Trump | Teixeira Exiled | Conclusion

In 2002, President George W. Bush stood astride the post–September 11 political world and Republicans looked poised to do the unthinkable and strengthen their positions in Congress in a midterm year. Yet liberal scholars John Judis and Ruy Teixeira published a provocative thesis: A new Democratic majority would “emerge” by the end of the decade. Traditional middle-class and working-class Democrats would be joined by growing ethnic minority populations, especially Asians and Hispanics; by working, single, and highly educated women voters; and by a growing share of the professional class, paving the way for a new majority. After President Barack Obama’s re-election in 2012, the thesis seemed airtight and its guidance likely to live long after the decadal horizon its authors had adopted. Except, just after the majority “emerged,” it started to crack. Judis observed surprising resilience in the Republican coalition and Republican strength with middle-class voters in the 2014 midterm elections, presaging the shocking election of President Donald Trump in 2016. By 2022, Judis and Teixeira’s “emerging majority” appears tottering, with Teixeira himself, a self-described “social democrat,” departing the Democratic establishment–aligned Center for American Progress for the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, in part because of institutional liberalism’s “relentless focus on race, gender, and identity.” But where stands The Emerging Democratic Majority at 20? How correct were its predictions, and can one find the seeds of the emerging majority’s demise in the book that declared it?

The year 2002 was not a good year to be a Democrat. George W. Bush had been elected president two years before and boasted stratospheric approval ratings thanks to the apparently successful military response to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Democrats had broken the Republican federal trifecta Bush carried into office—the first Republican federal trifecta since the Eisenhower administration—after the defection to the Democratic caucus of liberal ex-Republican Vermont Senator Jim Jeffords (I) but had to defend seats in states Bush had won. Making matters worse, charismatic left-progressive champion Sen. Paul Wellstone (D-MN) was killed in a plane crash while campaigning within two weeks of Election Day. And the midterm House elections were shaping up very differently than the usual midterms in which the president’s party typically loses seats: The GOP always looked likely to hold its majority with the potential to grow it.

These dynamics, and the hangover from their victory over Al Gore—popular President Bill Clinton’s Vice President—had Republicans and conservative commentators like Bush’s political consultant Karl Rove and Almanac of American Politics author Michael Barone speculating about the possibilities for a new, lasting Republican majority. Democrats had not won a majority of the national presidential vote since 1976, and in 1994, Republicans had broken the Democrats’ 40-year hammerlock on the U.S. House of Representatives. The Grand Old Party was riding high.

But amid this Republican ascendancy, two liberal scholars—New Republic editor John Judis and Century Foundation fellow Ruy Teixeira—published a provocative thesis backed by data: A new majority was on the cusp of power, but it would be Democratic, not Republican. In their imaginatively named The Emerging Democratic Majority, Judis and Teixeira argued that the country was on the cusp of transition from an industrial economy focused on suburban-urban and black-white divides with residual Protestant values to a postindustrial economy focused on “ideopolises” with secular-progressive values and a commitment to racial equality. That transition would grow the numbers of single women, immigrants, and professionals in the economy and, tantalizingly for the down-on-their-luck Democrats, the electorate would swing left. The old Democrats in organized labor, the white working classes, and African American communities would join with the “women’s movement,” immigrants, and professional workers to advance a new “progressive centrism” of secular values, abortion access, regulation of business, and a stronger welfare state.

While Bush’s Republicans won in 2002 (and 2004), the elections of 2006, 2008, and 2012 seemed to confirm Judis and Teixeira’s thesis in the main. Barack Obama’s Democrats dominated the Pacific Northwest, New England, the industrial Midwest, and the mid-Atlantic, as the “emerging majority” thesis predicted. Hispanic voters seemed to have moved Florida, Colorado, and Nevada firmly into the Democratic column while progressive professionals joined the traditional party base of liberal black Americans to turn Virginia blue and make North Carolina highly competitive.

While Texas, Arizona, and Georgia’s turns to the left were a bit beyond the decadal time horizon that The Emerging Democratic Majority took, liberal commentators could not help but note the same demographic dynamics that delivered Virginia and Colorado to the “rising American electorate” would deliver them to Obama’s successors. The GOP split harshly between a professional consultant-and-commentariat class that proposed liberal immigration reform as a desperate rearguard action to stem losses with Hispanic Americans and a populist activist-and-entertainer class that demanded the party double down on restrictionism. Liberals chortled at Republicans’ apparent no-win scenario, and the Democracy Alliance funded ethnicity-based and other identity-based outreach efforts to the New American Majority to whom the future belonged.

But even during the headiest days of the Obama era, there were skeptics of an emerging Democratic majority. Sean Trende, a political analyst with RealClearPolitics and the American Enterprise Institute, was perhaps the most prominent. His work, both at RCP and in his book The Lost Majority, questioned some of Judis and Teixeira’s key implicit and explicit assumptions like time-cyclical realignment theory, a high floor for Democrats with white voters, and the primacy of liberal immigration as a motivation issue for Latino and Asian voters. Most important for this counterthesis is the idea that American elections are driven by contingency—that is, in the possibly apocryphal words of British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, by “Events, my dear boy, events.”

By 2015, the results of the midterm elections of Obama’s presidency in 2010 and 2014 were impossible for Judis to ignore. Building off the unexpected election of Gov. Larry Hogan (R) in his home state of Maryland, he warned that, at least at the sub-presidential level, the “Democratic advantage of several years ago is gone.”

Two years later, the country inaugurated a Republican president who had done almost everything the emerging majority thesis, even as modified by Judis in his 2015 writing, would suggest was not how to win a presidential election. Donald Trump ran a campaign based on his belligerent persona, celebrity appeal to the white middle and working classes, and populist opposition to liberal trade agreements and illegal immigration. Trende would be left to write a post-mortem, deeming the emerging Democratic majority a liberal “God That Failed,” whose prescription of Clintonite progressive centrism had been superseded in political minds by a teleological assumption that capital-D Demographics would drive the Party of Jackson into near-permanent power.

In 2020, amid what may have been the worst political environment for an incumbent president since Herbert Hoover’s landslide loss in 1932, President Donald Trump lost the Electoral College by a combined 43,000 or so votes in three states. But even in defeat, Trump buried the emerging Democratic majority, perhaps to an even greater degree than he had in victory. Hispanics, especially in the overwhelmingly Mexican American Rio Grande Valley and the largely Cuban- and South American-descended portions of South Florida, swung firmly to the Party of Lincoln. Two Asian American Republicans joined Congress from districts in heavily Asian American Orange County, California. And the white working-class redoubt of Iowa, which Judis and Teixeira predicted would help anchor a Democratic majority, stayed staunchly Republican.

Whatever the new, likely fleeting, majority Joe Biden’s Democrats enjoy is, it is not the one that Judis and Teixeira predicted would “become the majority party of the early twenty-first century.” Emblematic of the Democratic Party’s departure from the “progressive centrism” the book espoused is Teixeira’s departure from the Democratic establishment–aligned Center for American Progress to the center-right American Enterprise Institute in July 2022 as he expressed increasing alarm at the Democratic Party’s deteriorating position with working-class and middle-class ethnic minorities.

Nothing in the rise and fall of the emerging Democratic majority suggests a Republican majority is inevitable: As anyone who lived through 2020 should know, events prevail over all political theories. But it is a warning against both hubris in the certainty of future victory and against despair at the prospect of future defeats. The political future, like the future of all things, remains unwritten.

In the next installment, Democrats interpret Barack Obama’s election as confirmation of the “emerging Democratic majority” thesis.