Foundation Watch

Milton’s Bittersweet Legacy: Too Much Money?

Milton’s Bittersweet Legacy (Full Series)

Too Much Money? | Unsavory Scandals

A Lawsuit Round Robin | Correcting the Course?

Summary: In this expansion of a March 2003 article, Martin Morse Wooster updates the complicated history of the Hershey Trust which runs and funds the Milton Hershey School. The 109-year-old organization, originally founded to provide aid and comfort to young orphans at the turn of the century, controls two profit-making enterprises, a unique situation in the foundation world. Not only does this tale offer a case study on how best to retain donor intent, it also portrays the sad decline of a great institution, presenting a record of recent scandal, financial impropriety, and sexual misconduct that has tarnished one of the most famous names in American philanthropy—and candy making.

In August 2016, Mondeléz International, a global snack-foods maker that owns Nabisco and other notable brands, called off an attempt to take over the Hershey Company. The companies Mondeléz and Hershey were uniquely compatible: Mondeléz makes Cadbury chocolates in every country except the U.S., where Hershey makes Cadbury bars under license.

The merger was rejected even though Mondeléz—a $30 billion-a-year enterprise compared to the Hershey Company’s $7 billion annual revenues—promised a signal act of self-abnegation: The combined company would be named “Hershey” would make its corporate home in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

The collapse of the merger, noted Wall Street Journal reporters Annie Gasparro and Dana Cimullca, “will likely reinforce the notion among analysts and investors that Hershey is unattainable as an acquisition in light of its majority ownership by a trust that for years has been reluctant to sell.”

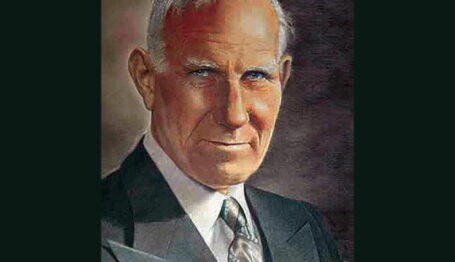

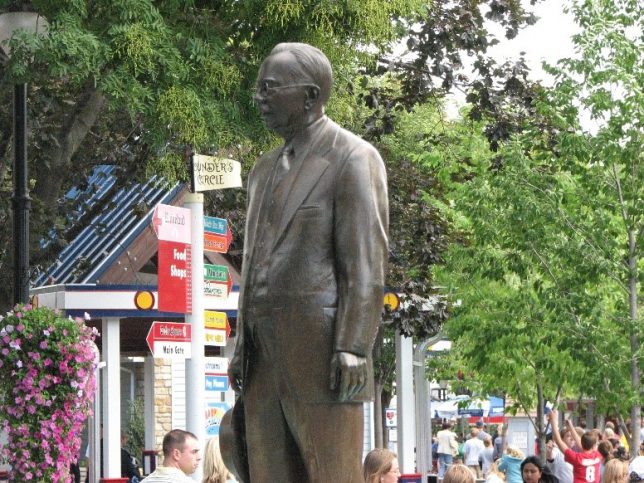

The organization controlling the Hershey Company is the Hershey Trust, devoted to protecting the interests of the Milton Hershey School, founded as an orphanage in 1909 by Milton Hershey. (Today, the school is a cost-free boarding school for children from lower income families.) With an endowment of over $12 billion, the Milton Hershey School is wealthier than any secondary school in the U.S. If the Milton Hershey School were a foundation, its endowment would make it the third largest in the U.S., with its endowment of $12.2 billion slightly less than the Ford Foundation’s $12.4 billion endowment.

The Hershey Trust currently controls 81 percent of the voting shares of the Hershey Company and completely controls Hershey Resorts and Entertainment, which owns a lot of property in Hershey, Pa., including the Hersheypark amusement park.

This unusual arrangement means that the Hershey Company might well be the only Fortune 500 company (it’s currently ranked #369) controlled by a charity. The Hershey Company is almost certainly the only major American company where a state attorney general, as the chief regulator of charities in Pennsylvania, has veto power over any potential merger.

The arrangement where a charity controls two profit-making enterprises would probably be illegal were it proposed today, because the Tax Reform Act of 1969 prohibits a charity from owning more than 20 percent of the shares of a corporation. Although the Hershey Trust now only controls 24 percent of Hershey common (including the non-voting shares) there has been no attempt to force the trust to give up control of the Hershey Company.

Unfortunately, in the past decade the Trust, has been rife with scandal, intrigue, and corruption. A seat on the trust’s board has proven quite lucrative, particularly for those members who simultaneously hold one of the three seats the trust maintains on the Hershey Company board. But the collapse of the Mondeléz deal should cast a strong light on the activities of the Hershey Trust, possibly leading to the conclusion that the current complicated relationship between the trust, the school, and the company is not the best way to preserve Milton Hershey’s charitable intentions.

Consequences of the Failed Wrigley Merger

The Hershey Trust and the Milton S. Hershey School’s problems are those of an organization that has far too much money for its intended purpose. Under the terms of the 1909 Deed of Trust, the Milton Hershey School is the sole beneficiary of Milton Hershey’s vast fortune. The courts have allowed one major deviation from the will, when in 1963 they permitted 25 percent of the Hershey School’s endowment to be used for the creation of a hospital now known as the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Center. Except for that deviation, courts have upheld Milton Hershey’s desire that the wealth created by the Hershey Company be used to support the school.

In its 2014 Form 990, the Milton Hershey School reported an endowment of $12.2 billion. Under the rule that states that foundations have to spend 5 percent of their endowment, this meant that if the school were a foundation, it would have to give at least $611 million in grants. However, the school’s annual budget is $259 million. The remaining $352 million sits in the Hershey School endowment.

In my March 2003 Foundation Watch, I explain the events leading up to a 2002 failed merger between the Hershey Company and the W.S. Wrigley Jr. Company. This merger was not only costly to the company and to the charitable sector in general,* it led to a protracted and costly legal battle.

For the opening salvo of the conflict, Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office launched an investigation of the Hershey Trust (paid for by the Milton S. Hershey Alumni Association, an independent nonprofit group of Milton Hershey School alumni that has no formal affiliation with the school). As a result of their investigation, the three entities—the association, the trust, and the attorney general’s office—entered into an agreement, which mandated the following:

- The overlap in the boards of the Hershey Trust, Hershey Foods, and Hershey Resorts and Entertainment would be eliminated, with no one being allowed to serve on more than one board.

- The school would stress the admission of needy children.

- The school would implement a foster care program.

- Academic standards for admissions and expulsions would be reformed.

- Land transfers and sales would be severely limited.

- The school would have to file biannual reports with Pennsylvania’s Attorney General.

But in 2003, the Attorney General’s office said that these clauses were tabled and would not be enforced. The Milton S. Hershey Alumni Association then sued the Milton Hershey School and the Hershey Trust to have the provisions of the agreement enforced. The resulting case, In re Milton Hershey School, took three painful years to work its way through Pennsylvania state courts. But in December 2006 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the case on a legal technicality, declaring that only the Pennsylvania Attorney General had standing to sue.

The alumni association, the court ruled, lacked standing because it was not created by Milton S. Hershey and therefore could not act as a check on the Hershey Trust’s power. “The Association’s intensity of concern is real and commendable, but it is not a substitute for an actual interest,” the court declared. “The Trust did not contemplate the Association, or anyone else, to be a ‘shadow board’ of graduates with standing to challenge actions the Board takes.”

In the next installment of Milton’s Bittersweet Legacy, we learn about the less savory scandals plaguing Hershey’s reputation.

* A 2008 analysis in the Columbia Law Review by University of Pennsylvania law professor Jonathan Klick and Florida State law professor Robert H. Sitkoff calculated that the Milton Hershey School’s endowment lost $2.7 billion by keeping the Hershey Foods shares rather than selling them.