Labor Watch

Big Labor’s Golden State: Rise of Industrial California

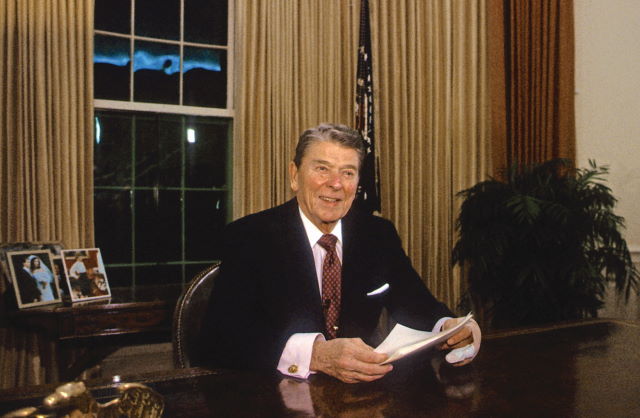

Ronald Reagan's battles with the Conference of Studio Unions, a militant labor organization that Reagan believed was Communist-influenced, triggered the political awakening that moved Reagan from the New Deal mainstream Left to the conservative Right that he would lead in the 1980s. License: Shutterstock.

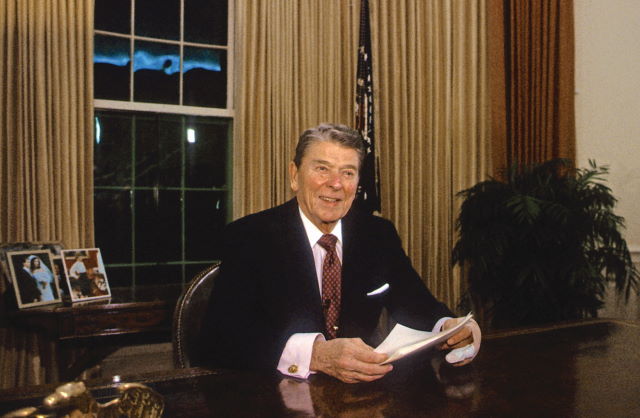

Ronald Reagan's battles with the Conference of Studio Unions, a militant labor organization that Reagan believed was Communist-influenced, triggered the political awakening that moved Reagan from the New Deal mainstream Left to the conservative Right that he would lead in the 1980s. License: Shutterstock.

Big Labor’s Golden State (full series)

A Tale of Two Cities | Rise of Industrial California

California’s Union Labor Machine | Ballot Power

World War II and the Rise of Industrial California

Labor relations nationwide were transformed by the New Deal, especially the passage of the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) in 1935. The law abolished the strong form of the open shop, requiring union monopoly bargaining where majority status was formally recognized, and effectively authorized various forms of the “closed shop” in which a contract could mandate union membership or payment of fees.

Oil was discovered in southern California in the 1910s. In the pre-Depression years the region had also developed the beginnings of an aeronautics industry. Both industries proved amenable to union organizing. Harvey Fremming, leader of the oil workers union, would become involved with John L. Lewis, head of the United Mine Workers, in the creation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) as a more radical alternative to the AFL. Aided by the NLRA’s aggressive support for union organizers, the aircraft plants in southern California buried the region’s historic antipathy to organized labor.

Anti-Chinese sentiment within organized labor continued to create headaches for organizing in San Francisco, ending only after a successful strike by Chinese-American workers backed by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in the late 1930s. Segregated locals in the AFL were common, notably the Boilermakers, which had a strong position in the shipbuilding trades. In 1945, state courts ordered the Boilermakers to integrate.

World War II brought a massive expansion in the defense industries that would persist to some degree until the end of the Cold War in 1991. With wartime “labor peace” rules came expanded union membership and organizing.

During the 1940s, widespread Communist infiltration of the California labor movement was alleged. Even sympathetic scholars have acknowledged that at that time “the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) was the largest organization on the political left and became an influential force in a number of unions.” Among the figures who rose to prominence combating that influence was Ronald Reagan, a film actor, anticommunist activist, and head of the Screen Actors Guild labor union. His battles with the Conference of Studio Unions, a militant labor organization that Reagan believed was Communist-influenced, triggered the political awakening that moved Reagan from the New Deal mainstream Left to the conservative Right that he would lead in the 1980s.

The longshoremen’s union, known as the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) after it split from the AFL-aligned International Longshoremen’s Association, was probably the most successful of the radical-left labor unions. While it was expelled from the CIO for the alleged Communist sympathies of its leader Harry Bridges, the union maintained its membership and grip on the West Coast ports, which it maintains to this day.

Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers

The National Labor Relations Act did not address farm worker organizing, in part to secure the support of Southern Democrats from segregationist states with large populations of black sharecroppers. While states have essentially no control over nonagricultural private-sector union-management relations (right-to-work laws being the principal exception), this leaves regulation of farmworker organizing under state control. California has among the most pro-union organizing rules in its large agricultural sector, codified as the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA), state legislation modeled on the federal NLRA.

The activism that led to the passage of the ALRA culminated in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the United Farm Workers led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta conducted organizing among the mostly migrant farmworkers throughout California. The most notable action was a boycott campaign against producers of table grapes that led to a series of UFW contract negotiations.

During the UFW organizing effort, growers aligned with the Teamsters Union, then deep in its Mob-influenced period, to secure contracts more favorable than those offered by the UFW. The growers and supporters of the Teamsters alleged the UFW was too radical. The UFW charged that the Teamsters engaged in a campaign of intimidation against UFW supporters.

In 1975, then-newly elected Governor Jerry Brown (D) would sign the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA), legislation that translated much of the National Labor Relations Act framework into California state law. The law created organizing procedures, mandated bargaining and in limited cases could dictate arbitrated contracts. And it established an Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) modeled on the NLRA’s National Labor Relations Board to administer the law.

Only one year into the ALRA system and amid disputes in the legislature about the ALRB’s funding and that led to a brief closure of the agency, Chavez and the UFW sought to enshrine the law in the state constitution through a ballot measure while also expanding UFW organizers’ power to enter growers’ lands. A spirited campaign against the measure from California Women for Agriculture saw the UFW’s ballot measure, titled Proposition 14, fail by a margin of two-to-one.

Placing Proposition 14 on the 1976 election ballot may have marked the height of Chavez’s and the UFW’s power. In the ensuing decades, especially since Chavez’s death in 1993, the UFW’s boycott and organizing power have crumbled, with the union reporting only 5,512 members in 2021. Left-of-center commentators have charged that the decline may have related to the staunch opposition to illegal immigration espoused by the Arizona-born Chavez, and the UFW’s unwillingness to organize illegal immigrant farmhands during his leadership.

In the next installment, government worker labor unions became the center of labor organizing in California.