Philanthropy

What We Owe the Dead: Defending Deceased Donors

This article originally appeared in RealClearBooks on August 24, 2018.

A provocative June article by Barry Lam on the always-interesting Aeon website wonders whether it is moral to respect the wishes of the dead over those of the living in the management and distribution of their wealth after death. It’s a question well worth pondering and trying to answer. Respect for the wishes of the dead is a central assumption in philanthropy, and elsewhere, and Lam’s article prods us to think about why so many see it as such a sound one.

“There is a huge industry dedicated to executing the wishes of human beings after their death,” Lam, an associate professor of philosophy at Vassar College, correctly notes. This “industry,” like many others, is contingent on policies enshrined in law. “Through endowments, charitable trusts, dynasty trusts, and inheritance law,” he writes, “trillions of dollars in the US economy and many legal institutions at all levels are tied up in executing the wishes of wealthy people who died long ago.”

After providing some examples of particular expressions of these wishes — “donor intent,” as it would be called in the context of grantmaking — and how they can be legally effectuated, Lam concludes, “These practices are, on reflection, quite puzzling.”

Both attacks on and appeals to donor intent are not new, and will continue. Earlier this year, for example, a Massachusetts state court allowed the struggling nonprofit Berkshire Museum to sell art donated to it for purposes of display there.

Joel L. Fleishman’s recent book “Putting Wealth to Work: Philanthropy for Today or Investing for Tomorrow?” describes the ways in which many establishment philanthropies have wrestled with donor intent. He accuses conservatives of exaggerating the degree to which donor intent is violated by American philanthropic pillars, including the Ford Foundation. Martin Morse Wooster’s “How Great Philanthropists Failed & You Can Succeed at Protecting Your Legacy,” new from the Capital Research Center (where I work), profiles donor-intent violations, including Ford’s, and offers advice about how to better honor donor intent.

A Foundational Attack on Donor Intent

Lam presents a more foundational attack on donor intent than most people, who, even in violating it, usually maintain a pretense of adhering to it. One of the things that puzzles Lam about donor intent is that the principle behind it is not equivalently applied in other contexts. In legal matters, for instance, dead people can’t vote, prevent their surviving spouses from remarrying, or run their companies anymore.

Lam does acknowledge that, even if only as a moral matter, a dying person can make his or her wishes regarding a spouse’s remarriage after his or her own death known to that spouse. “A promise itself holds some moral weight,” he says, “but not overriding moral weight.”

Whether asked in a legal or a moral context, Lam’s larger question is a good and challenging one: Why this beneficial deal for the dead when it comes to their wishes regarding their wealth? Why place the past above the present?

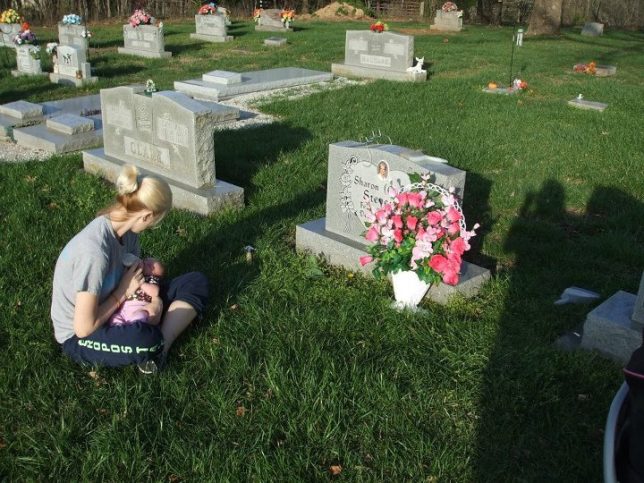

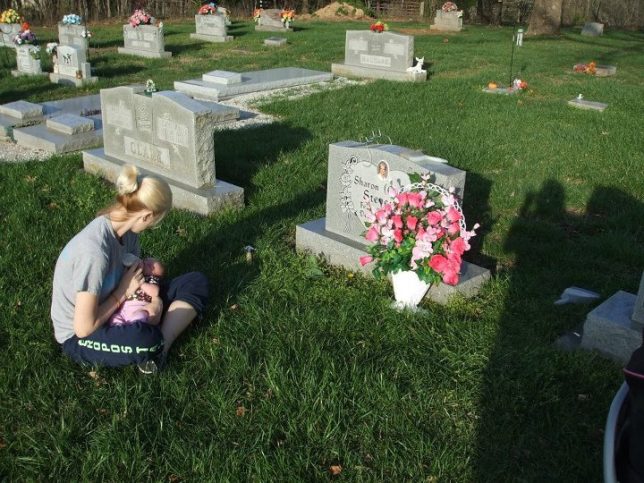

Whether you’re rich or not, morally or ethically, what do you think you owe your dead grandparents?

The Perils of Presentism

In answering his larger question, Lam touches on several arguments, many often made or invoked elsewhere by less bold skeptics of donor intent. However, his concluding reason we protect donor intent:

is that we have a self-interested desire that our own interests and values be preserved by future people after our own death, on pain that we disappear from the world without any legacy of influence. This existential fear we overcome by permitting institutions to honour the wishes of the dead in order to guarantee a place for our wishes in the future. But it is time to recognise the vanity and narcissism of the practice, and do what is actually best for the living, which is to have the living determine it for themselves.

Lam is willing here to allow “vanity and narcissism” to be meaningful measures of the morality of picking the past over the present, and he should, but this measure is equally applicable to the present. There might be some vanity and narcissism in us here arrogantly wanting “to guarantee a place for our wishes in the future,” but there is much more arrogance in automatically thinking we know better than the dead.

Presentism is bad enough when it prevents us, the living, from learning from about our own past, whether as individual donors or philanthropic institutions. It lessens or outright eliminates the benefit of accumulated knowledge and wisdom, which is worth something. In the context of philanthropy, while perhaps not strictly speaking arrogant, presentism risks inefficient and often ineffective grantmaking.

In terms of donor intent, the perils are even worse. In addition to inefficiency and ineffectiveness, there’s an additional moral risk that’s incurred: namely, breaking the cross-generational promise to the now-dead. This is also worth something, even to Lam. He just doesn’t think this promise has “overriding moral weight.” But, since we’re motivated by selfishness, there is outright arrogance in our breaking this promise — maybe vanity and narcissism, even.

We do not necessarily know better than our forebears, and we should not think so. We are certainly not better human beings by virtue of the mere passage of time. We might, I suppose, think we have more evidence to bring to bear on our judgments, but why on earth would we think we have more wisdom?

Our forebears — part of what some traditions would consider the “communion of saints” or the “democracy of the dead” — have some standing, to use a legal word, to complain if and when an important moral obligation like this is forsaken. They have an interest, and it should not go unrepresented. This is the reason for the existence of the “industry” Lam laments.

Those interests — donors’ intent — should not just arrogantly, cavalierly, and nearsightedly be overridden by us.