Organization Trends

The Need for Foreign Grant Disclosure by Nonprofits

IRS Form, Schedule F. Credit: Buy this Image Now. License: Shutterstock.

IRS Form, Schedule F. Credit: Buy this Image Now. License: Shutterstock.

The nonprofit sector has a major transparency problem—one that is aptly illustrated through the network of foundations and other nonprofits linked to pro-China megadonor Neville Roy Singham and his wife Jodie Evans. They reportedly used American tax-exempt entities to support Chinese propaganda efforts worldwide, according to an August 2023 New York Times exposé. However, current grant disclosure requirements make it impossible to identify many of the actual foreign recipients being funded through this network.

In December 2023, the Oversight Subcommittee of the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means held a hearing on the “Growth of the Tax-Exempt Sector and the Impact on the American Political Landscape.” Capital Research Center (CRC) president Scott Walter was invited to testify.

Committee members expressed interest in the nearly total lack of disclosure required of American nonprofits that make grants to foreign recipients—an issue on which CRC has previously written. Specifically, the Form 990 most nonprofits must file with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) each year requires them to identify their domestic grantees, but not their foreign ones.

Congress should work with the IRS and other interested parties to revise the Form 990 so that nonprofits are generally required to publicly disclose the same level of detail about their foreign grants as they are currently required to disclose about their domestic grants. Limited exceptions could apply in situations where disclosure would create a genuine security risk.

Grant Disclosure on the Form 990

First, a brief background on nonprofit grant disclosure.

Most nonprofits are required to file an annual return with the IRS called Form 990, which is also made available to the public. These forms are generally the most authoritative source of information about a given nonprofit’s financials, leadership, operations, and more. They are crucial to understanding how a nonprofit is fulfilling its tax-exempt purpose. Ordinary nonprofits such as 501(c)(3) public charities and 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations file the standard Form 990, while 501(c)(3) private foundations file the substantively different Form 990-PF.

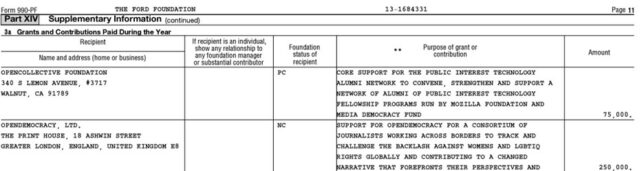

One of the most important pieces of information disclosed on both forms is grants paid during the year. Private foundations that file Form 990-PF must disclose the names and addresses of their domestic grantees alongside their foreign ones, meaning that there is typically little-to-no ambiguity about the recipient’s identity. For example, see this excerpt from the Form 990-PF filed by the Ford Foundation in 2022:

Ford Foundation, 2022 Form 990-PF

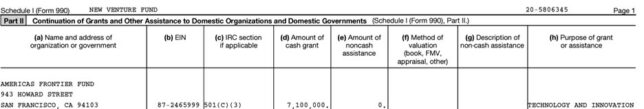

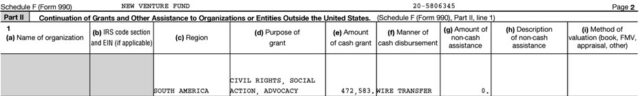

However, the standard Form 990 used by other nonprofits is considerably different. It splits domestic and foreign grants into two separate attachments (Schedule I and Schedule F, respectively) and requires disclosure of the names and addresses of domestic grantees. No such identifying information about foreign grantees is required on Schedule F, and the filing nonprofit need only disclose the amount of the grant, its purpose (which is often very vague), and the geographic region in which the recipient is located. Contrast the Ford Foundation’s disclosures with those of the New Venture Fund on its 2022 Form 990:

Schedule I (Domestic)

Schedule F (Foreign)

The bottom line is that nonprofits can make grants to foreign recipients with functional anonymity, and there is no way for the IRS or the public to see where the money is going. This is a major transparency problem in the tax-exempt sector—one that could be exploited.

Illustrating the Foreign Grantmaking Black Hole

To illustrate how this can all work in practice, consider the following example:

In 2017, the IRS granted tax-exempt status to a 501(c)(3) private foundation called the People’s Support Foundation. That same year, the foundation received a $160.2 million contribution from a mysterious entity called Mutod LLC. On its first Form 990-PF covering 2017, the People’s Support Foundation reported paying out a little over $3.2 million in grants, all of which went to specifically identified foreign recipients in countries such as South Africa, Brazil, and Zambia. So far, so good.

Over time, however, the ultimate recipients of funding from the People’s Support Foundation were effectively obscured by routing the money through nonprofit intermediaries that file the standard Form 990 and are thus not required to disclose their foreign grants.

A 501(c)(4) nonprofit called the People’s Welfare Association received its tax-exempt status from the IRS effective May 1, 2019. Tax filings covering that date through April 30, 2022 (three full fiscal years) show that the People’s Welfare Association brought in a grand total of $52,749,927 in revenue. While the fiscal years don’t align exactly, further tax filings covering January 1, 2019, through December 31, 2021, show that the People’s Support Foundation gave the People’s Welfare Association a total of $27,179,500. In 2020 and 2021, a full 99 percent of the People’s Support Foundation’s entire $24,887,500 total grantmaking went to the People’s Welfare Association. A separate group called the Justice and Education Fund gave the People’s Welfare Association an additional $8,148,000 from 2019 through 2021.

This is where the grant trail effectively ends. The People’s Welfare Association makes grants exclusively to recipients in foreign countries—totaling $50,888,520 from May 2019 through April 2022. As a 501(c)(4) nonprofit that files the standard Form 990, the People’s Welfare Association has never been required to disclose on its Schedule F the identities of the groups that received this money. If the People’s Support Foundation had made grants directly to foreign recipients (as it did in 2017, for instance), it would have been required to disclose them on its Form 990-PF. By routing the money through the People’s Welfare Association, the People’s Support Foundation effectively concealed its grantees.

There is a final wrinkle to all of this. The People’s Support Foundation is a 501(c)(3) private foundation, and the People’s Welfare Association is a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization. While a private foundation may give money to a 501(c)(4)—provided the funds are used consistently with its charitable purpose—it is very unusual for a private foundation to almost exclusively fund a 501(c)(4), particularly one that in turn passes the money to undisclosed foreign recipients.

American Nonprofits for Chinese Propaganda

These are not randomly selected examples. The People’s Support Foundation’s president is Jodie Evans, co-founder of the far-left agitation group Code Pink. Her husband is Thoughtworks founder Neville Roy Singham, and the People’s Support Foundation’s endowment was capitalized with proceeds from the sale of Thoughtworks to a private equity firm in 2017, reportedly for hundreds of millions of dollars.

Singham and Evans were the subjects of an August 2023 New York Times exposé detailing a “lavishly funded influence campaign that defends China and pushes its propaganda” centered around a number of U.S.-based nonprofits, one of which the Times identified as the People’s Support Foundation. According to the report, Singham was working “closely with the Chinese government media machine” and “financing its propaganda worldwide” by using “American nonprofits to push Chinese talking points.”

The Times reported on Singham’s connections to the Chinese Communist Party and his personal admiration of Maoism. It likewise noted that Evans is also a strong supporter of China and that she recently expressed a total inability to come up with a single negative thing to say about the communist country—save a minor gripe with its electronic payment applications. While the Times made clear that Singham was closely linked to all the American nonprofits in question and provided several examples of how their activities were aligned with Chinese government interests, it also observed that he appeared to have “sent his money through a system that concealed his giving.”

An earlier report by New Lines Magazine also explored Singham and his network in detail, noting that “in five years a web of organizations and individuals that promote apologetics for Beijing has emerged around Singham, and it all started with his sale of Thoughtworks in 2017.” Observing that Singham had “long held an ideological affinity with the Chinese Communist Party,” the magazine singled out the People’s Support Foundation for its “unmistakable bias in favor of the Chinese government.” The New Lines investigation into the foundation’s activities covered only through 2019, prior to its nearly total shift to funding the People’s Welfare Association and the People’s Welfare Association’s anonymous foreign grantmaking.

The main point is that this is not a hypothetical concern: Tax exempt groups located in the United States can be used to bankroll foreign organizations whose interests and activities are aligned with those of America’s geopolitical rivals. And most importantly, they can do so without any oversight or scrutiny.

The Next Steps

This simply should not be the case. The Form 990 should be revised so that American nonprofits are generally required to publicly disclose the identities of all their grantees—foreign and domestic. The IRS considered doing this back in 2007, but ultimately declined to move forward after receiving numerous public comments expressing concern that such disclosure could jeopardize the safety of those associated with a nonprofit’s work in dangerous foreign locations. Certainly, one can conceive of circumstances under which such concerns would seem plausible.

Commenters suggested that the IRS could instead redact identifying information about foreign grantees or not require reporting for every country, but the IRS responded that it “may not redact or withhold from public disclosure information reported on the Form 990 unless it is expressly authorized by statute.” Since it had been given no such authority regarding foreign grants, the agency decided to simply not request the information at all. Notably, the IRS also wrote that “if redaction or withholding from public disclosure becomes feasible in the future, Schedule F will be modified to require reporting on a country-by-country basis, as well as more specific grantee information.”

This should be an invitation for Congress to take up the issue, in consultation with the IRS and those with security concerns about disclosing the identities of their foreign grantees. Lawmakers could then craft a new disclosure framework for Schedule F that adequately addresses any legitimate safety concerns—perhaps through exempting certain “presumably unsafe” countries from detailed disclosure, or by allowing for a good-faith affidavit to be filed under defined circumstances that might permit limited redactions. At minimum, nondisclosure should be the conspicuous exception rather than the rule. This would go a long way toward shining a light into what is presently almost total darkness.