Philanthropy

Require Nonprofits to Disclose Their Foreign Grantmaking

Contemplating a framework for Schedule F that would default to full disclosure of all foreign grant recipients, but also provide an exception allowing for redaction when there is a genuine safety threat.

The House Ways and Means Committee recently announced an examination of, among other things, “whether foreign sources of funding are being funneled through [nonprofit] organizations to influence America’s elections.” That is a worthy investigation to perform, but there is another major transparency black hole involving funds flowing the opposite direction: from American nonprofits to foreign groups.

Currently, nonprofits are required to publicly identify their domestic grant recipients, but not their foreign ones. This should not be the case—all grantees should be disclosed—but the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has indicated that the particulars of requiring this would probably necessitate new statutory authority. Congress should work with the IRS and other interested parties to devise legislation allowing the agency to request this information from nonprofits on Form 990 and disclose it publicly, while also providing an exception in those cases where disclosure would create a genuine security threat.

Grant Disclosure on Form 990

Most nonprofits organized under § 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code are required to file Form 990 with the IRS every year. These are public documents, and they are generally considered to be the most-authoritative source of financial and other operational information about American nonprofits.

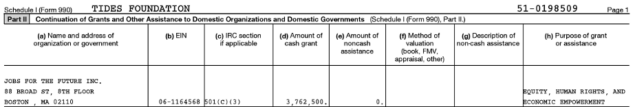

Depending on its activities, a nonprofit may be required to attach various schedules to its Form 990. One of these is Schedule I, wherein it lists all domestic organizations and governmental entities to which it gave more than $5,000 during the year. Each grant listed on Schedule I must include the grantee’s name, address, employer identification number (EIN), amount given, and the grant’s purpose.

Accordingly, there is usually little to no ambiguity as to the identity of each domestic grant recipient.

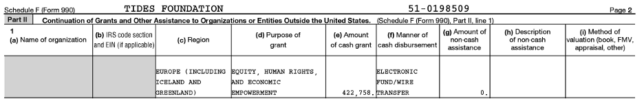

Nonprofits that make grants to foreign recipients report having done so on a separate schedule—Schedule F—under an entirely different disclosure framework. Crucially, the IRS instructs filers to omit the actual name of each foreign grantee, and disclose only the geographic region in which the grant was made (for example, Europe or South America), the amount and purpose of the grant (which is often very vague), and a handful of other minor bits of information. An example of a disclosure from the Tides Foundation’s 2021 Form 990 is illustrative:

Schedule I (domestic):

Schedule F (foreign):

The upshot is that it is impossible to identify a nonprofit’s foreign grant recipients using its Form 990. This is a rather significant transparency problem for the tax-exempt sector—one that is made even more conspicuous by the fact that Form 990-PF (used by private foundations) makes no such distinction between foreign and domestic grants. The Ford Foundation, for instance, discloses the names and addresses of its many foreign grantees right alongside those located in the United States.

Contrast that with the New Venture Fund, which is organized as an ordinary 501(c)(3) public charity. In 2021, it disclosed grants to more than 700 different domestic entities (mostly other nonprofits) on its Schedule I, all of which were specifically identified. It also listed over 200 grants to foreign recipients on its Schedule F, none of which was identified. With more than $1.1 billion in net assets and almost $330 million worth of grants paid in 2021, the New Venture Fund is the largest constituent member of the nonprofit network managed by Arabella Advisors—one of the most-important political and public-policy funding apparatuses in the country. Americans have every bit the interest in understanding its foreign grantmaking that they do in understanding its domestic.

Why No Disclosure of Foreign Grants?

Understanding why nonprofits do not identify their foreign grantees requires going back to the 2008 tax year, when the IRS implemented a package of revisions to Form 990. A background paper on the redesign explained that the agency had originally intended for the names of foreign grantees to be disclosed on Schedule F, but it had received numerous public comments from those who were concerned that making such information public could jeopardize the safety of individuals who worked with the nonprofit in dangerous foreign localities. Commentors suggested that the IRS should redact identifying information about foreign grant recipients, refrain from disclosing the information publicly, or not require reporting for every country.

The IRS responded by explaining that it “may not redact or withhold from public disclosure information reported on the Form 990 unless it is expressly authorized by statute.” Since it had been given no such authority for the information it was requesting on Schedule F, the agency decided simply not to request identifying information about a nonprofit’s foreign grantees. Notably, it clarified that “if redaction or withholding from public disclosure becomes feasible in the future, Schedule F will be modified to require reporting on a country-by-country basis, as well as more specific grantee information.”

Such safety concerns are valid, even if they represent a small minority of cases. There are certainly places in the world where grantees could be targeted for violence or harassment (from private parties or the government itself) simply because they received money from an American nonprofit. This is true even though private foundations freely disclose this information on Form 990-PF.

Improving Schedule F

So blanket nondisclosure is unacceptable because of the total lack of transparency, while blanket full disclosure is unacceptable because it could put people at risk. A compromise is necessary—a framework for Schedule F that would default to full disclosure of all foreign grant recipients, but also provide an exception allowing for redaction when there is a genuine safety threat. The IRS has indicated that something like this would require Congressional action, so Congress should give this issue its attention.

As for the specifics, it is impossible to imagine the IRS adjudicating each individual claim that a particular grantee’s identity must be withheld due to security concerns, so the judgment would almost certainly need to be left to the filing nonprofit’s discretion. Appropriate standards and safeguards against abuse would need to be developed to guide such a determination.

One approach could involve an affidavit or certification filed in conjunction with Schedule F, in which the filing nonprofit attests to having withheld identifying information about its foreign grantees for the sole purpose of protecting them (or others) from safety threats that it has a good-faith basis to believe exist. Congress or the IRS could conceivably produce a list of factors to be considered in this evaluation, potentially in conjunction with a list of “presumably unsafe” foreign localities. Disclosure of the country to which the grant was made could still be required, even when a grantee’s identity is redacted.

Whatever the particulars, the bottom line is that American nonprofits should be required to provide the same level of detail about their foreign grant recipients as they are currently required to provide about their domestic ones. Congress should devise a legislative solution that empowers the IRS to request this information on Schedule F and disclose it publicly, while also ensuring that nonprofits are able to adequately protect those associated with their work overseas from genuine threats of harm.

This article originally appeared in the Giving Review on September 5, 2023.