Special Report

Radical Lives Matter

An Old, Old Story

Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong. Credit: RootOfAllLight. License: Wikimedia.

Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong. Credit: RootOfAllLight. License: Wikimedia.

[ Intro | Organizational History | Intellectual History | BLM’s Place | Notes | Video: The Left’s Cult Leaders ]

There is nothing new under the sun.

Ecclesiastes 1:9

Are you surprised that as anarchists loot, a mainstream publisher issues, and National Public Radio boosts, a book that justifies looting? Why? Property is theft, the anarchist Proudhon declared in the 1800s, echoing a sentiment of the Marquis de Sade from the 1700s.

Are you surprised Black Lives Matter leaders call for ending the nuclear family? Why? In 1848 Marx demanded Abolition of the family! in The Communist Manifesto.

Are you surprised the establishment press believes injuries in this year’s urban violence are always caused by “police brutality”? Why? As a Black Panther in 1968, Eldridge Cleaver invented a bogus martyrdom-by-police for his comrade Bobby Hutton and fed it into the media via a white radical who became a Los Angeles Times reporter.[1]

In short, the radical ideas and violence associated with the Black Lives Matter movement are simply the latest eruptions of a type of left-wing politics that goes back decades, at least. Indeed, current movement leaders are tied directly to radical leaders and groups from a half-century of failed movements like Occupy Wall Street, Black Liberation, the Weathermen, Students for a Democratic Society, and the Black Panther Party. This unsavory political current also encompasses still more disturbing cases of extremism, including the Charles Manson cult and the Peoples Temple led by Jim Jones, notorious for a mass suicide in Guyana that took over 900 lives with poisoned Kool-Aid.

Some, like Alexander Solzhenitsyn and his fellow Soviet dissident Igor Shafarevich, as well as the philosopher Eric Voegelin, would argue that this kind of fanaticism goes much further back, that it is rooted in a permanent temptation of the soul to rebel against the human condition.

If these claims seem far-fetched, let us test them against the youthful Black Lives Matter movement by considering first its organizational history, then the intellectual history of its most prominent leaders, and finally its place in the history of left-wing movements in America.

Several themes will recur in these interconnected stories: political extremism based on Manichaean dualisms (“No bad protestor, No good cop,” for instance); education in Marxist-Leninist theory and adoration of Marxist-Leninist tyrants around the world; hatred of law enforcement personnel and the country whose laws they enforce; non-traditional (to say the least) families and sexual lives; and a tendency to leap from one extreme to its opposite (from pacifism to murderous violence, for example).

I leave it for others, more knowledgeable, to parse the details of controversial, allegedly racist shootings and to discuss how best to improve American policing. I affirm that black lives matter, because as a Christian I believe all lives are infinitely precious. But I also distinguish between the sentiment that black lives matter and the leaders of the movement so named. As I will show, persons enthralled by radical ideology often harm lives and enslave those whose suffering they use for their political ends.

[Intro | Organizational History | Intellectual History | BLM’s Place | Notes | Video]

Organizational History

The spark that first fired the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement occurred in 2013, when George Zimmerman, a Hispanic community watchman, was acquitted of murdering Trayvon Martin, a black teenager. Three self-described “radical Black organizers” responded: Alicia Garza wrote a “love letter” to black people in which she coined the phrase; her friend Patrisse Cullors turned it into the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter; and Opal Tometi started organizing people online and building the BlackLivesMatter.com website.

The 2013 killing of Trayvon Martin, a black teenager, was the spark that first fired the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. George Zimmerman, a Hispanic community watchman, was acquitted of murdering him.

The hashtag appeared only occasionally before August 2014, when Michael Brown Jr., another black teen, was shot by a white policeman in Ferguson, Missouri. This altercation, resulting in repeated protests against police, fanned the BLM spark, and leaders like Garza and DeRay Mckesson began to become better known. Yet the movement had internal struggles. Mckesson was said to aim for gradual political victories, while Garza became “fiercely protective” of the BLM hashtag, as friends told Buzzfeed in 2017. Garza wanted to pursue a truly radical agenda far beyond police reform.

Movement for Black Lives. Sometime in 2015 Garza and Tometi had a falling out. That same year the first organizational structure for the diffuse movement appeared: Movement for Black Lives. Its birth occurred at a BLM protest at Cleveland State University that was part of a meeting of numerous left-of-center groups like Blackbird, Black Youth Project 100, Million Hoodies, and OBS: The Organization for Black Struggle.

Movement for Black Lives has become BLM’s umbrella group, something the political Left tends to create for its causes. It claims a coalition of over 50 groups, but it has never incorporated. Instead, it remains a fiscally sponsored project of the Alliance for Global Justice, a nonprofit that acts as a pass-through for numerous radical organizations such as the Antifa-adjacent group Refuse Fascism. The Alliance was the conduit for foundation money to the ill-fated Occupy Wall Street movement a decade ago. Other beneficiaries of its services include groups that despise Israel and admire the dictatorial regimes of Cuba and Venezuela. The Alliance itself sprang from allies of the far-left Sandinista regime in Nicaragua, and its most extreme case of admiring tyranny appears in its coziness with North Korea. Its grantee Refuse Fascism has defended that brutal regime’s nuclear weapons, and its own website republished a fawning interview with North Korean tour guides that originally appeared in Workers World, the organ of the Marxist-Leninist party of the same name.

Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation. In 2016 the other most important entity appeared, the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation. It, too, has never incorporated, which allows it to escape the transparency required of most nonprofits, who must file annually with the IRS and disclose salaries, expenses, vendors, board members, and the like. It was originally a fiscally sponsored project of Thousand Currents, a nonprofit pass-through for multiple groups.

Susan Rosenberg supported feminism, antiwar groups, the violent Weather Underground, the Black Liberation Army, and so on. Her own adventures stalled when she was arrested in 1984 with hundreds of pounds of stolen explosives and an extensive arsenal of weapons. Credit: Sky News Australia. License: https://bit.ly/3lDhS2w.

The board of Thousand Currents is co-chaired by Susan Rosenberg, whose own political history is dramatic. Her family was Jewish and middle-class, and she attended Barnard, becoming an all-purpose radical in the 1960s. That is, she supported feminism, antiwar groups, the violent Weather Underground, the Black Liberation Army, and so on. She was also one of the lesbian co-founders of America’s only woman-led terrorist group, the May 19th Communist Organization. Its history is well recounted in William Rosenau’s Tonight We Bombed the U.S. Capitol. The group’s name commemorated the shared birthday of black separatist Malcolm X and Vietnam dictator Ho Chi Minh. The group was notorious for its role in three policemen’s deaths in the 1981 Brinks robbery and for the jail-bust that freed the cop-killer Assata Shakur (aka, Joanne Chesimard), a member of the Black Liberation Army who fled to communist Cuba, where she remains today.

Susan Rosenberg’s adventures stalled when she was arrested in 1984 with hundreds of pounds of stolen explosives and an extensive arsenal of weapons. (The group had been spurred to new heights of intensity by its fear that a Republican President would be re-elected.) A court sentenced her to 58 years, but on his last day in office President Bill Clinton commuted her sentence. Rosenberg went on to be a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, to donate her papers to Smith College, and to pen a 2011 memoir, An American Radical: A Political Prisoner in My Own Country, in which she shows no remorse: “I pursued a path that seemed to me a logical step beyond legal protest: the use of political violence. Did that make me a terrorist? In my mind, then and now, the answer is no.”

Patrisse Cullor’s 2017 memoir When They Call You a Terrorist echoes these sentiments. Its opening epigraph comes from lines of Assata Shakur that echo Marx’s Communist Manifesto:

It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.

This July, the fiscal sponsorship of Black Lives Matter Global Network was transferred from Rosenberg’s Thousand Currents to the Tides Center, part of a $636 million-a-year network of left-of-center groups run from the Presidio in San Francisco. As of August 2020, the BLM Global Network’s site BlackLivesMatter.com lists 17 local chapters but claims dozens more. It is a member of Movement for Black Lives.

The BLM Global Network calls for defunding the police, an idea so radical that the race-baiting Al Sharpton, who came to prominence slandering policemen over a racial hoax, has disavowed it. The Network also brags it “disrupt[s] the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure requirement.”

The Movement for Black Lives is arguably more radical. It declares that “prisons, police and all other institutions that inflict violence on Black people must be abolished and replaced by institutions that value and affirm the flourishing of Black lives.” It adds that “Black people will never achieve liberation under the current global racialized capitalist system.” Using a term pioneered by the dictators Stalin and Mao, it has a “five-year plan” under which “We will establish self-determined Black communities where Black people are in governing power in at least 5–10 localities over the next five years.”

The Movement also wants taxes and welfare programs to achieve “a radical and sustainable redistribution of wealth,” the nationalization of natural resources, regulations to create a parallel black-controlled economy (black-owned banks, credit unions, etc.), the abolition of private education, and, until recently, divestment from Israel. On its website it explicitly links the BLM protests in Ferguson back to radical 1960s protests. Its 118-page Reparations Now Toolkit cites such 1960s groups as the Black Panthers, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Republic of New Afrika, and more. The same Toolkit declares, “we wholeheartedly endorse and support” N’COBRA (the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America), which last year gave its Reparations Lifetime Achievement Award to the anti-Semitic demagogue Louis Farrakhan.

Lesser groups are also involved in the movement. For instance, Black Lives Matter at School annually sponsors a weeklong protest and “educational” event held since 2017 in cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Textbooks and guides describe the country (“the American empire”) and its schools as systematically racist, and the National Education Association teachers’ union supplies major support. Its website has the same Communist Manifesto–echoing poem from Assata Shakur that opens Patrisse Cullors’s memoir.

Funding is not likely a worry for these organizations. This year has seen an explosion of support from Fortune 500 corporations and philanthropies like George Soros’s Open Society Foundations, which recently pledged $220 million. Already the major BLM groups have been receiving millions from the Ford Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, the NoVo Foundation (created by Peter Buffett, son of billionaire Warren Buffett), and other megadonors. Total “commitments from foundations to combat systemic racism have topped $1 billion” just since May, the Chronicle of Philanthropy reported in August. Corporate Goliaths like Amazon, Microsoft, Fitbit, and Cisco promise millions more. The Democracy Alliance, a donor cabal co-founded by Soros to push America leftward, was an early adopter of this strategy. Politico reported that as early as 2015, the Alliance’s wealthy members were encouraged to give significant support to BLM.

[Intro | Organizational History | Intellectual History | BLM’s Place | Notes | Video]

The Leaders’ Intellectual History

Now let us see what is in the minds of the BLM leaders who will spend these millions.

Opal Tometi. Of the three black radical women said to have founded the movement, Opal Tometi is the least well known and least currently active. In June 2017, Tometi explained, “I have not been involved in the day-to-day organizational and fiscal management of [BLM] since December 2015.”

After the shooting of Trayvon Martin and subsequent acquittal of George Zimmerman, Opal Tometi, a self-described “radical Black organizer,” responded by organizing people online and building the BlackLivesMatter.com website. Credit: TED Conference. License: https://bit.ly/36CXgkA.

She was raised in Phoenix, the daughter of Nigerian immigrants, and attended the University of Arizona, where she earned her bachelor’s in history (focusing on black history) and her master’s in communication and advocacy. Before BLM, she was executive director at the Black Alliance for Just Immigration for eight years.

She says her family suffered “injustices,” such as her mother and aunts having workplace troubles and her father being pulled over “for driving while black.” She also “had extended family members who were in immigration detention and an aunt who was deported.” In her collegiate studies of black history, she “soon realized” she had been wrong to think “Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X and Rosa Parks and all these great leaders I’d read had accomplished the dream or had got us closer.”

Currently living in “the Republic of Brooklyn,” her BlackLivesMatter.com biography says, “She is a student of liberation theology and her practice is in the tradition of Ella Baker, informed by Stuart Hall, bell hooks and Black Feminist thinkers.” As “a transnational feminist, Opal supports and helps shape the strategic work of Pan African Network in Defense of Migrant Rights, and the Black Immigration Network (BIN) international and national formations respectively, dedicated to people of African descent.”

Patrisse Cullors. Patrisse Cullors, by contrast, has deeper ties to this country. She was born in Van Nuys, California, and raised in the San Fernando Valley in a mostly Hispanic neighborhood. Her life story is told in her memoir, and it is not simple or without pain. Her mother became pregnant at 15 and was thrown out of the house by her Jehovah’s Witnesses family. Forbidden to speak to her family or anyone at the Witnesses’ Kingdom Hall except the Elders, her mother spent years trying to rejoin the congregation, finally achieving that when Cullors was a teenager.

Patrisse Cullors asked Angela Davis to write the foreword to her memoir. Davis applauds the way Black Lives Matter “has encouraged us to question the capacity of logic—Western logic—to undo the forces of history, especially the history of colonialism and slavery.” Credit: Laura Flanders Show. License: https://bit.ly/2K1s2vG.

Her mother had more children, and their father, who worked at a GM plant, was able to support them until the plant closed. This caused parental turmoil, and when Cullors was six, he ceased to live with the family, though he didn’t “disappear entirely from our lives.” Then when she was 12, Cullors the middle child was told that, actually, that man isn’t her father. “Alton is not your father, [mother] says. He’s Paul’s and Monte’s and Jasmine’s. But in between Monte and Jasmine, we broke up and I fell in love with Gabriel and we had you.”

Patrisse had never seen this man, but her mother offered to take her to him. He turned out to be from a Catholic family with roots in Louisiana. They were far less emotionally repressed than Patrisse’s family, and unlike Witnesses, they celebrate Christmas, Thanksgiving, and birthdays. She liked this large but poor family (her father had nine siblings) and soon learns her father is graduating from a Salvation Army drug and alcohol treatment program. He had long suffered from drug addiction and been jailed for that and for his small-time drug-dealing. Looking back now, Cullors wasn’t keen on the Army’s stress on individual responsibility, but she sees it did much to help her father.

In a few years, however, Cullors is crushed again when her father returns to prison, once again on drug charges. Around this time, her brother Monte begins to have serious drug problems, going first to juvenile hall, then to prison. He is diagnosed with a schizophrenic condition. Cullors herself was arrested at the age of 12 because she had been smoking marijuana in school.

In high school, she was in a magnet program with a humanities curriculum “rooted in social justice”: “We study apartheid and communism in China. We study Emma Goldman and read bell hooks, Audre Lorde. . . . We are encouraged to challenge racism, sexism, classism and heteronormativity.” She began to question “the Jehovah’s Witnesses world I had come up in.” The final straw was watching the Witnesses “reinstate” her mother.

“I always knew I wasn’t heterosexual,” she writes, and she “came out” in high school. By senior year, she and a friend “are completely on our own, couch surfing” or sleeping in cars. After graduation, an art teacher lets the girls live with her and teaches them Transcendental Meditation. This experience spurs her ideas about “intentional families,” as opposed to biological ones.

In her senior year of high school, though she “had never in my life been attracted to a heterosexual, cisgender man,” a young man in the grade below changes that. “He is super attractive: tall and fair-skinned and with the greenest eyes I’ve ever seen.” He was a man “named Mark Anthony, a brother who would become my first husband.”

She earned her bachelor’s in religion and philosophy from UCLA and an MFA from USC’s Roski School of Art and Design. She describes how she and Mark Anthony read together: “bell hooks continues to be a North Star but Cornel West’s work, as well, takes center stage.” They also “love” the feminist anarchist Emma Goldman. Cullors especially admired how the Russian émigré was the first American to defend homosexuality publicly, and quotes Goldman’s disdain for monogamy.

In her memoir, written with asha bandele (sic), the acknowledgments praise other thought leaders, most on the radical left:

We do this work today because on another day work was done by Assata Shakur, Angela Davis, Miss Major, the Black Panther Party, the members of the Black Arts Movement, SNCC, the RNA [Republic of New Afrika, a black separatist group with ties to Susan Rosenberg’s May 19th Communist Organization], Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Ella Baker, and so many others.

Angela Davis is so important to Cullors that she asked Davis to write the memoir’s foreword, where Davis sneers at the fact “Assata Shakur was designated by the FBI one of the world’s ten most dangerous terrorists.” Davis applauds the way Black Lives Matter “has encouraged us to question the capacity of logic—Western logic—to undo the forces of history, especially the history of colonialism and slavery.” Davis, who twice ran for vice president on the Communist Party USA ticket during the days it was controlled by the Soviet Union and who has never expressed remorse for her card-carrying days, uses the communist term “comrades” to describe Cullors’s colleagues in the movement. Their “approaches . . . represent the best possibilities for the future of our planet.” In the memoir itself, Cullors lauds Davis’s short book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, which predates BLM’s founding by over a decade.

Angela Davis, who twice ran for vice president on the Communist Party USA ticket during the days it was controlled by the Soviet Union and who has never expressed remorse for her card-carrying days.

More recently, Davis capitalized on the movement with another brief tome, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. It features a foreword by Cornel West and a blurb from Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Black Panther imprisoned in 1981 after he first shot a police officer in the back as the officer was arresting a third man, and then shot the officer four more times. Radicals have long insisted on Abu-Jamal’s innocence, despite the multiple eyewitnesses who saw the shooting, three more eyewitnesses who heard Abu-Jamal admit in the hospital that he had shot the officer and hoped the man would die, and the ballistics evidence that showed the lethal bullets had been fired from his gun. Abu-Jamal’s blurb for Davis’s book confirms that BLM is just another expression of the radicalism in which Davis has labored for so long (she turned 72 the year it was published): “This is vintage Angela: insightful, curious, observant, and brilliant, asking and answering questions about events in this new century that look surprisingly similar to the last century.”

Angela Davis’s own great antecedent is Herbert Marcuse, as Roger Kimball explains in The Long March: How the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s Changed America. Kimball notes Marcuse was Davis’s mentor and called her the best student he ever taught. Kimball’s summary of the German thinker neatly fits Cullors, the radical performance artist, organizer, and “queer” activist promising followers freedom: “Marcuse blends Marx and Freud to produce an emancipatory vision based on polymorphous, narcissistic sexuality, antibourgeois animus, and quasi-mystical theories about art, redemption, and the abolition of repression.”[2]

One more radical theorist of importance to Cullors is Frantz Fanon, a thinker from Martinique known for praising the use of violence to throw off colonial rule. A Pan-Africanist, he also taught that truth is whatever serves the revolution: “Truth is that which protects the natives and destroys foreigners.”

Cullors praises Fanon in an article for the Harvard Law Review, which raises the issue of her own privilege. Few non-lawyers receive space in such elite pages. Similarly, her memoir was published because, after she spoke on a panel on Martha’s Vineyard with Hollywood stars Danny Glover and Issa Rae, a book editor from St. Martin’s asked her to write it. Cullors has also received numerous honors, including a Fulbright Scholarship, Glamour magazine Woman of the Year, an honorary doctorate from Clarkson University, and been named one of the World’s Greatest Leaders by Fortune.

A final major influence on Cullors reinforces her powerful ties to aging left-wing movements. After high school, her art teacher friend sends her to a “social justice camp,” which deepens her belief that the world is filled with deep “hatred” for the victim groups with which she associates herself. There she was enchanted by an activist group, Strategy Center, and went for a year’s training as an “organizer.” “I read, I study, adding Mao, Marx and Lenin to my knowledge of hooks, Lorde and [Alice] Walker.” Most importantly, the Center’s founder, Eric Mann, “[took] me under his wing.” She mentions him only once in the book, and tells none of his long radical history, but elsewhere she calls the Center “my first political home,” which shaped her for more than a decade.

Mann was no mere organizer. Half a century ago, he served on what was essentially the central committee of the violent Weather Underground, alongside such infamous terrorists as Bill Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn. During those years he was arrested for many violent offenses, and though he was often released by authorities he did spend 18 months in prison. His punishment stemmed from a 1969 shooting at a police building, for which he was charged on four counts: conspiracy to commit murder, assault with intent to commit murder, promotion of anarchy, and threatening. Afterwards—one is tempted to say, “naturally”—he became a journalist, penning a Boston Globe column with radical historian Howard Zinn.

Mike Gonzalez of the Heritage Foundation reports that Mann remains a radical who calls America “the most dictatorial country in the world,” describes his work as training “young people who want to be revolutionaries,” and reminds his students that unless you’re an organizer, “your life is meaningless” and you risk becoming a “bourgeois pig.” In a nod to the socialist dictatorship of Venezuela, Mann calls his Strategy Center, “the University of Caracas Revolutionary Graduate School,” and he lauds universities’ role in radicalizing students. “The university,” he explains “is the place where Mao Zedong was radicalized, where Lenin and Fidel were radicalized, where Che was radicalized.” His goal for students is to “take this country away from the white settler state” and have an “anti-racist, anti-imperialist, anti-fascist revolution.”

Alicia Garza. Alicia Garza, the third of BLM’s founders, may be the starkest in her radicalism. When Verso (Latin for Left) Books decided to publish a third edition of Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao, and Che, they asked Garza to write the foreword. She brings to the new edition not only BLM chic but also years of engagement with its content. She read the book “as a young organizer” but couldn’t properly grasp it: “I hadn’t yet studied much of the origins of the Marxist-Leninist tradition that I was loosely trained in.” Now “after nearly 20 years of organizing and building a movement,” she finds it invaluable. We’ll see why when we consider where BLM fits in the history of left-wing politics.

Alicia Garza, the third of BLM’s founders, may be the starkest in her radicalism. Her summer with SOUL (School of Unity and Liberation) in Oakland taught her community organizing but also, she added, “analysis around capitalism and imperialism and white supremacy and patriarchy and heteronormativity.” Credit: Citizen University. License: https://bit.ly/3lADuME.

SFWeekly reports that Garza grew up in San Rafael, California, and attended “an almost all black and brown elementary school.” Then her parents moved to “Tiburon, a tiny and tony Marin County town” whose median household income more than doubled the state’s average. It is also “one of the whitest places in the Bay Area.” Her mother and stepfather were antiques dealers, but her classmates assumed she lived in subsidized housing because of her color. She became an activist in middle school, fighting abstinence-only education. She tells the reporter her parents are “solid liberals” who aren’t especially political, yet her mother inspired this first activist venture.

Like Cullors, Garza identifies as queer and was deeply shaped by a far-left “training program for social justice organizers” she attended after college, as she explained to SFWeekly:

When I trained in sociology, we would read Marx, and we would read de Tocqueville, and we would read all these economic theorists, but in a void,” she says. “It never got mentioned in those classes that social movements all over the world have used Marx and Lenin as a foundation to interrupt these systems that are really negatively impacting the majority of people.”

Her summer with SOUL (School of Unity and Liberation) in Oakland taught her community organizing but also, she added, “analysis around capitalism and imperialism and white supremacy and patriarchy and heteronormativity.” Next Garza worked for PUEBLO (People United for a Better Life in Oakland), fighting a proposed Walmart. She didn’t care that poor black residents actually wanted the Walmart, nor that the local labor council supported the new store, which did open. She also had organizing jobs at places like the UC Student Association and POWER (People Organized to Win Employment Rights). A top POWER campaign fought against development in Bayview, a predominantly black community, with help from local clergy, the Sierra Club, and especially the Nation of Islam, which sent members to stand on every floor of City Hall.

After POWER, Garza was hired in 2014 by the National Domestic Workers Alliance, a left-leaning union front group underwritten by political powerhouses like the SEIU (Service Employees International Union) and billionaire-sized philanthropies like the Ford, MacArthur, and Open Society Foundations. The Alliance wanted Garza to boost its organizing of black domestic workers, especially in the South. They sent her to Ferguson after the Michael Brown shooting, which led BLM to “the next step in its transformation from a hashtag to an organization by mobilizing 600 black activists from around the country to embark on ‘freedom rides’ to Ferguson for a weekend of protests,” SFWeekly observes.

But even this heightened activism and reach did not satisfy Garza. She told the reporter she wants to ensure “Black Lives Matter doesn’t get co-opted by the Democratic Party or by black activists who want to reform policing but balk at more radical action.” This leads us to the question of where BLM fits in the history of left-wing politics.

[Intro | Organizational History | Intellectual History | BLM’s Place | Notes | Video]

BLM’s Place in the Left’s History

Although BLM leaders occasionally give brief nods to Martin Luther King Jr., they put far greater emphasis on radical black leaders of the 1960s and 1970s, especially the violent Black Panthers. Cullors’s memoir, for example, lauds the Panthers four times, describing them as “another group of young Black activists,” like BLM, “who had come together around police violence.”

It’s debatable how radical King’s own critique of America was, compared to that of the Panthers and other extremists. It is not debatable that he rejected the violence of radicals like the Panthers and Stokely Carmichael. Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton coined the term “institutional racism” in Black Power: The Roots of Liberation (1967), which is the origin of today’s more popular equivalent, “systemic racism.” (Wikipedia redirects searches for systemic racism to its page on institutional racism.)

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton coined the term “institutional racism” in Black Power: The Roots of Liberation (1967), which is the origin of today’s more popular equivalent, “systemic racism.” Credit: KBOO. License: https://bit.ly/3f6HNgn.

Besides the question of violence, the other great source of the dichotomy between King and the radicals was separatism, or “ethno-statism” as we would say now. Carmichael was such a separatist that he broke with the Panthers because they refused to exclude white people from their group. This prophet of “systemic racism” then moved to Africa and changed his name to Kwame Ture to honor two African tyrants, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, a megalomaniac who hoped to create a Union of African Socialist Republics, and Ahmed Touré, who killed tens of thousands of his fellow Guineans.

David Horowitz, then a fellow radical working with Panthers like Huey Newton, reports the contempt radicals felt for King and his philosophy of nonviolence and Christian love. Horowitz’s attachment to radicalism began to fade after the Panthers killed a female accountant friend he had encouraged to work for them. His essay “Black Murder, Inc.” catalogs many other crimes, most also never dealt with by police, including embezzlement (the Panthers liked “fancy cars and clothes”), drug dealing that often ended in violence, arson, beatings, and extortion. Panthers even used bull whips, “the very symbol of the slave past,” Horowitz notes, on their brothers and sisters. They tended to recruit members from street gangs, including Elaine Brown, whose own memoir recorded a Panther leader telling her, “Other than making love to a Sister, downing a pig [i.e., a cop] is the greatest feeling in the world.”[3]

Horowitz wonders how the Black Panthers, including Brown, could justify their actions as responses to anti-black racism by the police, even as the police didn’t enforce the law against them in so many cases, including the murder of his white accountant friend. He finds the answer in Brown’s memoir. She explains how she accepted Huey Newton’s bloody brutality to his colleagues: “Faith is all there was. If I did not believe in the ultimate rightness of our goals and our party, then what we did, what Huey was doing, what he was, what I was, was horrible.”[4]

Horrible as the Panthers were, worse was possible. Some Panther members, concerned Newton wasn’t violent enough, split off and formed the loosely organized Black Liberation Army, including Assata Shakur, who along with Angela Davis tops the pantheon honored by BLM leaders. Susan Rosenberg also moved in these still-more-radical circles, as did Eric Mann’s Weather Underground, which had split from the less violent Students for a Democratic Society.

Many of us today think that these groups from the 1960s and 1970s were mainly fired by opposition to the Vietnam War and President Nixon. We forget that race and hatred of police formed powerful parts of their creeds. Then, as now with BLM’s leadership, the agenda is driven by many issues, all involving revulsion against current conditions, a revulsion that can become overpowering.

For example, we forget that obsession with race drove groups like Charles Manson’s commune “The Family,” whose members were recruited in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury during the “Summer of Love.” Manson taught them that race war was imminent, with outraged blacks soon to massacre whites. He hoped to spark the war with violence like his gang’s notorious murder of pregnant actress Sharon Tate in Beverly Hills. In response to Tate’s death, Eric Mann’s fellow Weatherman Bernadine Dohrn exulted at a “war council”: “Dig It. First they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them. They even shoved a fork into a victim’s stomach! Wild!”[5] As she ranted, psychedelic posters of Castro, Lenin, Mao, Malcolm X, and Black Panthers looked down. The same meeting featured, one repentant participant recalls, “crazy discussions” of whether “killing white babies was inherently revolutionary, since all white people are the enemy.” (Of course, most of the Weathermen were privileged white youths.)

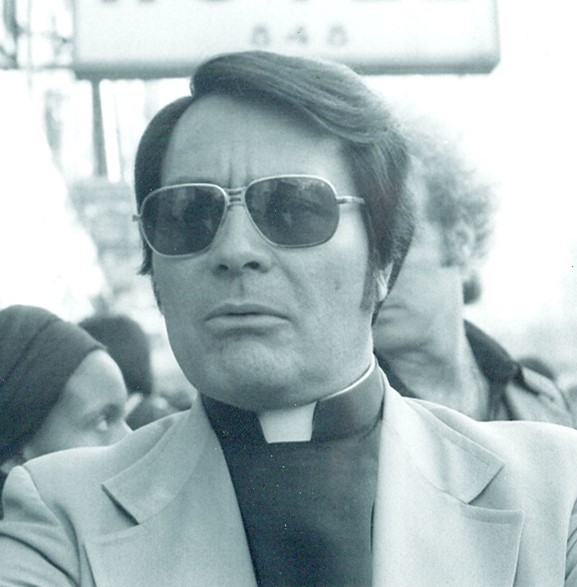

Admittedly, Manson was far from sane and in recent decades has appeared fond of the Nazi version of totalitarian socialism, but another notorious killer from this era was less obviously insane and far, far more lauded by the radicals of that day, including Angela Davis: the Rev. Jim Jones, the founder of the Peoples Temple who presided over one of the largest mass suicides in modern history.

Rev. Jim Jones, the founder of the Peoples Temple, presided over one of the largest mass suicides in modern history.

When college age, Jones attended Stalin-era Communist Party meetings. He had the savvy insight that straightforward preaching of communism draws few to it, but Christian tropes could draw far more. By the time the Peoples Temple had moved from Indiana to San Francisco and become better known, Jones was much blunter about his preference for Marx and Mao over Christianity, though in addition to being the reincarnation of Lenin, Father Devine, and Gandhi, Jones said he was also the reincarnation of Jesus.

Jones only fled to Guyana in his last year, fearing the law. In his San Francisco days he recruited followers with help from Black Panthers and other left-wing groups, and he was lauded by both the Left and the Democratic Party, including Gov. Jerry Brown and a rising state legislator, Willie Brown, who would go on to become mayor as well as speaker of the California Assembly (and mentor/lover of Kamala Harris). “San Francisco should have ten more Jim Joneses,” Brown declared, and he savored how Jones turned out hundreds of volunteers to campaign through poor black neighborhoods to help elect Democrats.[6] Later, Brown would help Jones visit communist Cuba, writing Castro that Jones was a “close personal friend and a highly trusted brother in the struggle for liberation.”[7]

On that trip, Jones visited one of his heroes, Huey Newton, then hiding out in Cuba from murder and assault charges. In his invaluable study of Jones, Cult City, Daniel J. Flynn explains how Jones and Newton discussed the latter’s book Revolutionary Suicide on the trip. While Newton’s work had “a different vision” from Jones’s eventual Kool-Aid massacre, the Panther’s book preached a left-wing fanaticism that was a step on the way to the horror in Jonestown, which occurred a year later: “Chairman Mao says that death comes to all of us,” but while “to die for the reactionary is lighter than a feather,” to “die for the revolution is heavier than Mount Tai.”[8]

As reporters and lawmen began uncovering Jones’s various abuses and crimes, he urged his mostly black followers ever more strenuously to resist his enemies. Newton and Angela Davis stuck by this avowed anti-Christian Marxist, going so far as to let Jones call them from Guyana so they could exhort his communards over the loudspeakers that harangued the captives for hours a day. As Flynn writes, Angela Davis “fed Jonestown paranoia by telling residents of ‘a very profound conspiracy’ against Peoples Temple.”[9]

Again, few now have an accurate understanding of Jim Jones’s project. We assume he was some religious crank; his Wikipedia tagline is “American preacher.” Yet for decades he declared his contempt for Christianity and his devotion to Marx, communist dictators like Stalin[10] and Castro, and a radical political agenda. For example, he extolled Cuba in general, only complaining that it should be more zealous in its support of abortion and homosexuality. (Jones himself sexually abused both men and women, including at least one underage boy.)[11]

Jones especially traded on the politics of poverty and race. As he wrote to a San Francisco Chronicle reporter in his final year, “the society we are building in Guyana has given people who were considered the refuse of urban America a new sense of pride, self-worth, and dignity.”[12] Actually, Jones exploited his mostly black, working-class followers not only sexually but financially. The Peoples Temple largely lived off the Social Security checks of elderly black women members,[13] and low-income workers were expected to “contribute” up to 40 percent of their salaries.[14] Jones passed some of these expropriated funds to his political allies like Angela Davis.[15]

Meanwhile, notes Jones’s definitive biographer, mostly white church leaders routinely went to restaurants and movies, while “the rank and file—mostly poor and black—did without.”[16] In a final hypocrisy, white men were much more likely to escape death in the mass suicide than less favored demographics: White men were only 10 percent of Jonestown’s population but 19 percent of the survivors, while blacks of both sexes made up about 70 percent of both population and deaths. Black women likewise were about half the population and the deaths.[17]

One other notable hypocrisy: Jones and his left-wing admirers liked to claim the Peoples Temple supported Gandhian nonviolence, but some members were known “for enlivening the services by screaming, ‘Kill ’em all, kill ’em all!’”[18] Biographer Reiterman observes that Jones “through fear, violent rhetoric, and fakery,” both condemned “leftist and antiwar violence” and also “conditioned his people gradually to accept defensive violence” until he’d taught them: “attack at my command and in defense of principle—socialism—and of me.”[19]

In short, Jim Jones and Peoples Temple reveal how radical politics can exploit people’s suffering, even to the point of death. Jones’s confederate Mike Prokes wrote a reporter near the end, “we’ve found something to die for and it’s called . . . social justice.”[20] Two left-leaning professors explain how social justice ended up requiring death:

Temple members were encouraged, if not required, to participate in traditions of social and political activism beneficial to their own group and to the broader concerns of the progressive left in and around the San Francisco Bay area in the 1960s and 1970s. Such political participation . . . contributed to a powerful sense of collective destiny. This destiny called for making the ultimate self-sacrifice: dying together to protest the conditions of an inhumane world.[21]

In his last recorded words, Jones echoed his friend Huey Newton, “We didn’t commit suicide, we committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.”[22] One fears that kind of angst is not too far from Patrisse Cullors’s despair at her father’s funeral. She blames his death, not on drugs, but on this white supremacist country: “If my father could not be possible in this America, then how is it that such a thing as America can ever be possible?”[23]

But this bloody path is only one avenue down which radicalism travels. Call it the path of purity, for radicalism has historically thrashed back and forth between two poles: power and purity. On the one hand, the Left lusts desperately for power, which often requires winning elections, but on the other, the Left and its numerous factions distrust each other and condemn those who fail purity tests.

Recall how BLM disrupted Bernie Sanders on the campaign trail in 2016. Alicia Garza put him to a test and found him wanting. She complained he is only a “social democrat,” slightly left of the Democratic Party, who offers “not socialism” but only “democratic capitalism.” She wanted “more voices saying, ‘This is not actually socialism, and socialism is actually possible in our lifetime.’” So on some days, it appears that even if every law Bernie Sanders desires were enacted, it wouldn’t satisfy Garza or Angela Davis, or the utopian cravings of many left-wing eruptions through American history like the People’s Climate March, Occupy Wall Street, the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, the Black Panthers, the Vietnam War protests, and more.

But on other days, radicals like Garza aim for the opposite, practical pole of gaining power. In her foreword to the book on 1960s radicals turning to communism, she condemns unrealistic leftists who act as if “people don’t use elections as a vehicle” for “taking power.” The book’s author, Max Elbaum, rhapsodizes over Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign. Elbaum, a veteran of the “New Communist Movement,” explains how radicals should appreciate that political campaign: “The Jackson/Rainbow effort was not the ‘1917 to come’ that revolutionaries of the early 1970s expected. But it was definitely a large-scale flow of popular resistance.” He wishes it had combined multiple left-wing factions across races and issues, and also organized better. Note that BLM’s vanguard is now beginning to execute just such a strategy.

Anne Sorock of the Frontier Center spoke to dozens of BLM enthusiasts at all levels in 2016 and found them jubilant so many left-wing strands were coalescing and enjoying more success in affecting the culture than any time since the 1960s. And that was well before the outpouring of foundation and corporate millions into their coffers, the protests and riots of 2020, and the sycophancy of so many Fortune 500 corporations. But though a 1960s-level success would have significant consequences for America, the movement is still doomed to fizzle out as utopian demands meet reality.

Some activists will “sell out.” Recall how many “tuned in, turned on, dropped out” hippies ended up enjoying a cozy corporate life. One black revolutionary who publicly threatened professor Walter Berns as he led faculty opposition to the radical take-over of Cornell in 1969 later became CEO of the financial giant TIAA-CREF and signed Berns’s pension checks.

Other activists will cling tightly to purity and discover to their despair what Elbaum concedes: America is a “deeply conservative country,” which explains why his beloved New Communist Movement is “a once-dynamic but now all-but-disappeared political current.”[24] As I write, embarrassing polls show that black and Hispanic support for Donald Trump increased. In the New York Times, two Hispanic activists dolefully report that when they asked voters if they condemned “illegal immigration from places overrun with drugs and criminal gangs” and supported “fully funding the police, so our communities are not threatened by people who refuse to follow our laws,” three-fifths of blacks and whites agreed, while an even higher proportion of Hispanics agreed. This finding by no means guarantees the President’s re-election, but it does mean Marxist-Leninist revolution in the name of people of color faces mountainous odds.

Unfortunately, radical true believers rarely care that they cannot persuade most of those in whose name they claim to speak. Think of Alicia Garza fighting a Walmart that the local poor people of color wanted, or read her foreword to Elbaum’s book, where she laments that even members of radical organizations aren’t well-aligned with the “paid staff organizers” ruling over them.[25]

The greater misfortune is that we will always have with us the radicals’ roiling hatred of the world as it is. One could cite Saul Alinsky for this truth: in Rules for Radicals he praises “the very first radical . . . who rebelled against the establishment and did it so effectively that he at least won his own kingdom—Lucifer.”[26]

Or one could cite Solzhenitsyn, who observed that the socialist dream is millennia old. His friend Igor Shafarevich published a valuable study of radical utopianism over the last 2,000 years,[27] in which he observes that this permanent temptation of the soul is entwined with an obsession with death. Sartre, for example, quotes with approval his fellow radical Paul Nizan, who returned from the Soviet Union declaring, “A revolution that does not make us obsessed with death is no revolution.”[28] Shafarevich concludes that “Understanding socialism as one of the manifestations of the allure of death explains its hostility toward individuality, its desire to destroy those forces which support and strengthen human personality: religion, culture, family, individual property.” And the same hostility explains the radical “tendency to reduce man to the level of a cog in the state mechanism, as well as with the attempt to prove that man exists only as a manifestation of nonindividual features, such as production or class interest”—or race or gender expression, we must now add.[29]

Radicalism today may be doomed, but it can still be deadly. Garza certainly takes the life-and-death stakes seriously. SFWeekly reports she has six lines from June Jordan’s “Poem about My Rights”[30] tattooed on her chest. They end, “my resistance . . . may very well cost you your life.”

Scott Walter is president of the Capital Research Center, which operates InfluenceWatch.org, from whose research this article draws.

[Intro | Organizational History | Intellectual History | BLM’s Place | Notes | Video]

Notes

[1] David Horowitz, Hating Whitey, 213.

[2] Roger Kimball, The Long March: How the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s Changed America, 167.

[3] Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story, 140-41, quoted in Horowitz, Hating Whitey, 120.

[4] Horowitz, Hating Whitey, 122, quoting Brown, A Taste of Power, 353.

[5] Mark Rudd, Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen, 189. Years later, Dohrn began claiming her comment was an ironic joke.

[6] Tim Reiterman, Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People, 266-67.

[7] Daniel J. Flynn, Cult City: Jim Jones, Harvey Milk, and 10 Days That Shook San Francisco, 58.

[8] Huey Newton, Revolutionary Suicide, 6.

[9] Flynn, Cult City, 216.

[10] “You’re never gonna make me dislike that man,” Jones said of Stalin, “no matter how many tales you tell me.” Duchess Harris and Adam John Waterman, “To Die for the Peoples Temple,” in Moore, Pinn, and Sawyer, Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 117.

[11] Marshall Kilduff and Ron Javers, The Suicide Cult: The Inside Story of the Peoples Temple Sect and the Massacre in Guyana, 53-54. Kilduff and Javers were reporters who long covered Jones for the San Francisco Chronicle.

[12] Kilduff, The Suicide Cult, 199.

[13] See Rebecca Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” in Moore, Pinn, and Sawyer, Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America.

[14] Kilduff, The Suicide Cult, 82.

[15] Kilduff, The Suicide Cult, 46.

[16] Reiterman, Raven, 222.

[17] Rebecca Moore, “Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple,” in Moore, Pinn, and Sawyer, Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 64.

[18] Kilduff, The Suicide Cult, 184.

[19] Reiterman, Raven, 199.

[20] Kilduff, The Suicide Cult, 199-200; ellipsis in the original.

[21] Duchess Harris and Adam John Waterman, “To Die for the Peoples Temple,” in Moore, Pinn, and Sawyer, Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 120-21.

[22] Duchess Harris and Adam John Waterman, “To Die for the Peoples Temple,” in Moore, Pinn, and Sawyer, Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 103.

[23] Cullors, when they call you a terrorist, 108.

[24] Elbaum, Revolution in the Air, xvii.

[25] Garza, foreword to Elbaum, Revolution in the Air, ix.

[26] Alinsky, Rules for Radicals, ix.

[27] Igor Shafarevich, The Socialist Phenomenon (New York: Harper and Row, 1980).

[28] Quoted in Shafarevich, The Socialist Phenomenon, 285.

[29] Shafarevich, The Socialist Phenomenon, 293.

[30] “Poem about My Rights”by June Jordan

. . .

I am not wrong: Wrong is not my name

My name is my own my own my own

and I can’t tell you who the hell set things up like this

but I can tell you that from now on my resistance

my simple and daily and nightly self-determination

may very well cost you your life