Philanthropy

Ideas Cost More Than They Used To. How Will Policy Donors React?

This article originally appeared in RealClearPolicy, April 20, 2018.

I recently saw a billboard in Milwaukee that asked, “What idea is worth $10,000?” It urged its viewers to watch Channel 12 on Saturday to see who would win the money for an entrepreneurial idea, as part of something called Project Pitch It. Like other nationally televised shows, the effort is meant to entertain and to encourage entrepreneurialism.

Policy donors, of course, offer financing for ideas as well: how to nationalize health care, for example, or deregulate the airlines, or protect privacy from Big Tech. Both in these realms and in entrepreneurship, a good idea usually costs well north of $10,000. And there’s good reason to think that these kinds of ideas are getting even more expensive, requiring investors and policy-oriented givers to act judiciously and intelligently.

Last September, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) released an interesting working paper by four academic economists, “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?” They summarize it in this article. Citing figures about the decades-long overall economic slowdown in America and Europe, they ask, “Will this slowdown in growth persist, or is a ‘fourth industrial revolution’ about to begin, possibly encouraged by breakthroughs in computing, robotics, and artificial intelligence?”

As the authors, Nicholas Bloom, Chad Jones, Michael Webb, and John Van Reenen, write in the article, “This debate has morphed into an argument about how many innovations are out there to discover.” But they find this “single-minded focus on the quantity of undiscovered ideas” misguided:

It is not just how many ideas for productivity growth are left, but what it would cost to get them out of the ground — and, crucially, how much we’re prepared to spend to do it. … Just as newer oil sources are increasingly costly to extract, coming up with new ideas is getting more expensive.

While the target audience of the NBER paper is essentially economists, those investing in policy programs can gain insight from the study as well.

The authors show that “the costs of extracting ideas have increased sharply over time.” Specifically, they attempt to measure declining “research productivity” in industries, products, and firms where they felt they could fairly, accurately, and numerically determine inputs and outputs.

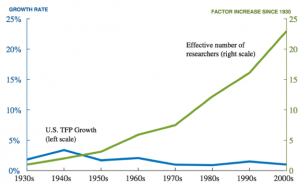

To measure the rate of growth in the output of economy-wide research, they use U.S. “total factor productivity” growth: “the part of output growth left after accounting for inputs of labour [sic], capital and other factors.” As illustrated by the left scale in their figure (below), the rate has declined over time since the 1940s. To measure research input, they simply use the number of researchers in the economy. As shown by the figure’s right scale, it increases more than 20 fold. The authors conclude: “So, more than 20 times as many researchers are needed today to generate about the same amount of productivity growth as 80 years ago.” More than 18 times as many are needed than in the 1970s.

Policy outputs are obviously more difficult to measure than the economic growth rate, since more policy is not always good policy, especially for those favoring limited government.

Policy inputs are difficult to fairly measure, too, though one can try. A February study by my Capital Research Center colleague Michael Watson and me examines the publicly available revenue figures in 2006 and 2014 for nonprofit policy and advocacy organizations that received financial support from top conservative and liberal philanthropies. The more than 1,400 groups studied do more than just produce ideas — they disseminate, promote, and sometimes help implement them — but they are, for the most part, in the “ideas business.”

In 2006, these organizations’ revenues together totaled just over $6.2 billion. In 2014, they were $9.6 billion — an almost 55 percent increase in a mere eight years. This 2014 figure is consistent with an estimate by David Callahan in his book “The Givers,” where he writes “We’re probably talking about a sum in the low billions, less than $10 billion.”

In the context of economic growth, the economists suggest that “research is like any other input — there are likely to be diminishing returns.” New results require more education, more specialization, more researchers — and, hence, more money. The same seems to be true in policy investment. Once more invoking the oil metaphor, they conclude:

We are digging deeper into a trickier part of the rock. Of course, we could be wrong and humanity may have just have been chipping away at a particularly hard point that will soon give way, creating decades of cheap ideas. This is the hope of those who emphasise [sic] the revolutionary power of artificial intelligence. … Although we all enjoy science fiction, history books are usually a safer guide to the future. In this case, history suggests that large increases in research effort are needed to offset its declining productivity.

In the policy context, a continued increase of funding for ideas may be difficult for givers to maintain, though many may consider such an increase more important than ever. Whether they can and will give more, as the Project Pitch It billboard in Milwaukee said, “Watch to find out.”