Green Watch

America’s Rare Earth Ultimatum: A National Policy of Vertical Integration

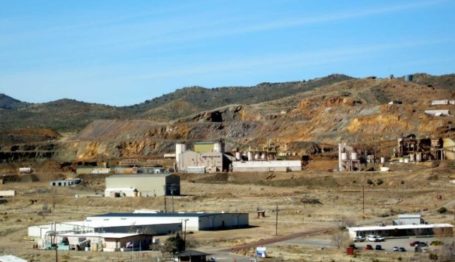

An aerial photograph of a Chinese rare earth mining operation.

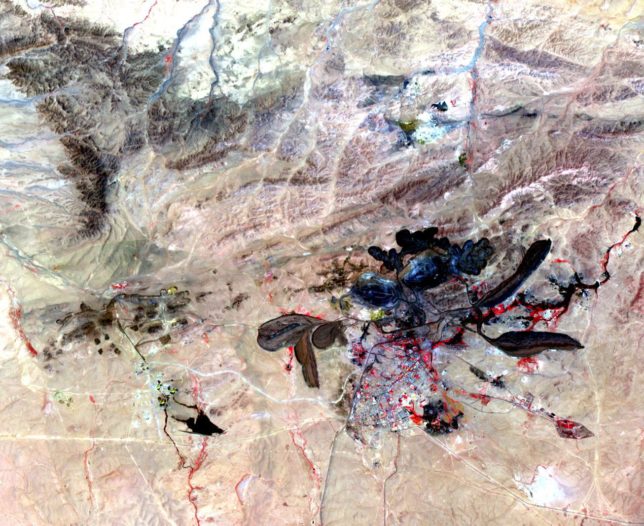

An aerial photograph of a Chinese rare earth mining operation.

America’s Rare Earth Ultimatum (full series)

Rare Earths in High Demand | Made in China | A National Policy of Vertical Integration | A Solution to Rare Earth Market Failure

Summary: For the past decade, our dependence on rare earths has conjured up considerable attention, fascination, and concern regarding their importance. This has caused a cascading effect to create interest and investment in other rare metals, critical minerals, ore deposits, mining, and the American mineral endowment—all related to with U.S. technology manufacturing, national security, military readiness, geopolitics, and trade, particularly with China. Rare earth elements have become the poster child for critical minerals, especially those for which we are 100 percent import dependent—the vast majority of which come from China.

What’s Really at Stake

The connection between rare earth elements, technology metals, and corresponding supply chains and the U.S. high-tech manufacturing sector, renewable energy, and military readiness is now very well-established. They all require rare earths in large quantities. For the world’s largest economy, largest energy renewables market, and most powerful military—the stakes cannot be higher.

Yet, the U.S. has not invested enough money or attention to guarantee an adequate supply of rare earth elements.

Despite the crisis of confidence occurring in the rare earth trade space outside of China, during the decade between 2008 and 2018 the U.S. government spent less than $25 million on solving what a GAO report referred to as a “bedrock national security issue.” Japan, having already been directly affected by a rare earth embargo, spent more than $1.5 billion, but was still just as dependent on China for rare earths as it was in 2010.

Since 2002, the key U.S. technology and defense sectors have been 100 percent reliant on China for all imported rare earth materials. Simply stated, for almost two decades the American “critical minerals credit card” has been maxed out with high-interest accruing yearly to China!

Because of American dependence on imported rare earths and the Chinese supply chain, the United States’ technology companies will need to continue moving to China—compromising the intellectual property of cutting-edge technology—fulfilling China’s well-earned reputation for violating intellectual property. Another significant reason that companies are moving is cost: foreign companies using Chinese rare earths to manufacture items in China for export are not hit with quotas or charged export or value-added taxes.

Perhaps the best example of the impact of China’s dominant position in rare earths has to do with the most ubiquitous of all manufactured products today—the smartphone. It certainly appears that Apple was forced to manufacture its iPhone and other electronic products in China in order to maintain access to a steady supply of rare earths.

As a consequence, China copies and reproduces Apple’s products on an industrial scale. China, in the fourth quarter of 2015, sold more of its iPhone knock-offs worldwide than Apple sold iPhones. By September 2017, Apple had experienced declining sales for six months in a row in China, the world’s largest mobile-phone market. Chinese phone makers are making headway in and out of China, and they account for roughly half of the global market.

This trend could continue because there is no other supply chain to challenge or stop it. China’s growing expertise in manufacturing their own brand of high-quality products (near-perfect copies of the market leaders’ brands, after all) and lower costs could eventually displace Apple and others on a global basis. How much is mega-brand loyalty worth? We may soon find out.

As companies are forced to move to China to gain access to rare earths in order to manufacture their products, this continual threat to intellectual property greatly diminishes American leadership positions in strategic industries. U.S. companies—Intematix, GE (Healthcare/MRI Division), Ford (Starter Motor Division), and Battery 1,2,3—have all added manufacturing capacity in China, and so has Japan’s Showa Denko, Santoku, and scores of other global electronics companies.

China is also the world’s leading producer of all renewable energy products, largely due to their control over rare earths. They dominate the solar panel and wind turbine markets. China leads the world in next-generation nuclear technology, with more experimental reactor programs than the rest of the world combined. They have publicly stated and demonstrated that they intend to lead the world in the design, production, and distribution of both carbon-free forms of energy—nuclear and renewables.

Similarly, most of the world’s green and automotive technologies use China’s rare earth-dependent “component capture” strategies. This means China also manufactures most or all of the products closely associated with rare earths, providing it with the world’s most fully integrated rare earth component supply chain monopoly.

The Congressional Research Service in 2013 published a well-received report on rare earths and their relationship to U.S. national defense. The report addressed the effect of Chinese rare earth materials policies as they affect U.S. companies this way:

The Chinese government has announced a number of initiatives over the past few years to further regulate the mining, processing, and exporting of rare earth elements, such as consolidating production among a few large state-owned enterprises and cracking down on illegal rare earth mining and exporting. The Chinese government contends that its goals are to better rationalize and manage its rare earth resources in order to slow their depletion, ensure adequate supplies and stable prices for domestic producers, obtain a more favorable return for exports, and reduce pollution. Critics of China’s rare earth policies contend that they are largely aimed at inducing foreign high-technology and green technology firms to move their production facilities to China in order to ensure their access to rare earth elements, and to provide preferential treatment to Chinese high-tech and green energy companies in order to boost their global competitiveness. Such critics contend that China’s restrictions of rare earth elements violate its obligations under the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Regarding national security and military readiness, the defense industry’s fear of rare earth supply disruption, and the desire to maintain and grow their businesses and other product lines through Chinese contracts, has given China tangible control over their financial fortunes. Most of the U.S.’s advanced weapon systems procurement (see Rare Earth Dual-Use Technology textbox above) depends entirely on China for advanced metallurgical materials. To punctuate that fact, a March 28, 2017, Senate Energy and Natural Resource Committee hearing on U.S. critical minerals supply concluded that the U.S. is not making headway and has actually increased its dependence on rare earths and other critical minerals from the previous year (2016).

The best-known GAO report on the subject of national security risks and rare earth materials described it this way:

The Department of Defense (DOD) depends on rare earth materials (rare earths) to provide functionality in weapon systems components. Many steps in the rare earths supply chain, such as mining and refining the ore, are primarily conducted outside the United States, which may pose risks to continued availability of these materials to DOD. For example, in our prior work conducted in 2010, we found that much of the rare earths processing is performed in China, giving it a dominant position that could affect worldwide supply and prices. U.S. industry previously performed all steps in the rare earths supply chain and produced the majority of the global supply but no longer has the capability.

This dependency could provide China with some influence, and possibly control, over the outcome of any future conflict with the U.S., according to GAO. However, the Defense Department has done little to address the rare earth supply chain issue for over 20 years—since the sale of Magnequench to China in 1995, and the initial closure of the Mountain Pass rare earth mine in 1998. The DOD’s Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) maintains very few rare earth elements on hand. The DLA in 2016 did award a contract for purchases of yttrium and dysprosium, but for the amounts of rare earth materials needed by defense contractors, stockpiling is not the answer.

Bottom line, there is little our military can do with stockpiles of minerals, especially rare earths, without a reliable processing and manufacturing supply chain to make the needed critical items. The meager stockpiles of rare earth materials maintained by DLA would still need to be shipped to China for processing into metals for use. However, an American firm holds six U.S. patents for a new rare earth processing technology to produce a pure form of rare earth concentrate with thorium removed. This could be one step in giving America a fighting chance to compete again in the rare earth trade space.

Rare Earth Monopoly—The Business Side

China’s monopoly of the global rare earth market should be no surprise–they are the pioneers of rare earth innovation and are the authors of rare earth development history as previously discussed. Today, China is by far the world’s leading researcher, producer, and exporter of rare earth minerals and metals.

According to production figures for rare earths in China obtained by USGS, officially-licensed Chinese mines churned out roughly 105,000 tons of rare earths, or approximately 85 percent of world output in 2016. However, in addition to government licensed mines, China has a huge thriving artisanal and illegal or black-market mining industry that has been largely overlooked by reporting agencies and organizations both domestic and worldwide.

Official Chinese government rare earth production for 2016 is set at 105,000 tons. However, knowledgeable experts have recently estimated that black-market rare earth production in China was 150 percent higher during the same period, or roughly 157,000 tons. In other words, the total rare earth production of China is on the order of 260,000 tons—not surprisingly approaching 95 percent of global output.

In response, China’s central government ordered hundreds of rare earth mining and processing facilities consolidated under just six major companies, presumably with the goal of maintaining concentrated oversight and control.

The higher production figures suggest that Western estimates consistently underreport Chinese rare earth production on the order of 150 percent annually. This solidifies the importance of Chinese illegal production as an unknown quantity or “wild card” that handily contributes to price fluctuations on the world market. Fluctuations, or even price fixing, serve as a tool for China to further undercut U.S. or others’ investment in rare earth development by keeping the price low enough to deter new players in the marketplace, helping the Chinese maintain their global rare earth monopoly.

As further evidence, the output of illegal production for 2017 appears to be even higher than 2016. And in 2018, the Chinese Ministry of Industry increased China’s rare earth production quota (the allowable amount of rare earth mining output) by a whopping 40 percent over 2017 to at least be comparable to black market production.

The Chinese government has a system to handle supposed “illegal” rare earth production. When discovered, if the mine operators are willing to pay taxes, penalties, and conform to new environmental standards, these “artisanal” or “mom and pop” mines” are allowed to continue production. Despite China’s enormous rare earth mining output, it is still not enough to satisfy demand.

Not only is the world utilization of rare earths climbing, but China’s domestic requirements for rare earths is exploding along with their ever-increasing middle class and demand for cleaner energy. China’s population currently consumes nearly 70 percent of the world’s rare earth output, much of which is converted in their manufacturing facilities into LED lighting, iPhones, and PCs which are then purchased by consumers around the world.

China in 2018 imported an all-time high quantity of rare earth elements produced elsewhere. Their rare earth imports are up 167 percent year over year, while simultaneously minimizing their rare earth mine depletion. The 2018 Chinese rare earth import volumes are ten times higher than 2015 figures, suggesting that government crackdown on “illegal” domestic production may be at least partially responsible for the surge in recent rare earth imports into China.

Today, China is simultaneously the world’s largest exporter and importer of rare earths. For now their position as the world’s rare earth leader is extremely enviable, but a tipping point may have been reached, at least regarding their domestic production and resources. For example, China has 30 percent of the world’s rare earths reserves and probably no more, and may need to begin cutting, rather than increasing national mining quotas, despite their domestic rare earth demand.

But the Chinese appear to have a backup plan to obtain additional rare earth supplies. Using their global reach of resources, the Chinese are tapping into major rare earth deposits and mining projects elsewhere, such as in Greenland, Canada, Australia, and Burundi (neighboring the war-torn African countries of Rwanda and the Congo). All of these projects will have China as a major customer, as minerals and metals mined almost anywhere outside China find their way back there for processing, because China’s leaders spent the past 60 years designing the world’s most sophisticated rare earth supply chain network.

The key to China’s real monopoly power stems from their ability to couple rare earth reserves and mining output worldwide, with the uniquely Chinese rare earth value-added supply chain that churns out metals, alloys, and a long list of technology products beginning with the all-important high-strength rare earth magnet.

From the beginning of its rare earth industry until now, China steadily has increased its dominance to perhaps as high as 95 percent of the market. Their global control means they are in a position to leverage the combination of overproduction and price manipulation to bankrupt global rare earth competitors, if and when they choose to do so for political, economic, or military advantage.

Unfortunately, Western scientific and technical efforts have thus far failed to develop new reliable, cost-effective rare earth substitutes—thereby maintaining China’s monopoly. American universities have slowly stopped offering course studies and advanced degrees in materials science, metallurgy, mineral industry, and mining engineering, forcing bright minds to seek internships and jobs off-shore rather than contributing to the U.S. economy.

Even academic and scientific conferences are now dominated by China’s restrictive media and educational policies, instead of open forums to discuss issues of importance to the entire world, this despite the Department of Energy’s push to create the Critical Minerals Institute in 2013 at various National Labs around the country.

An important lesson to our elected officials may be that it was the Western nation’s penchant for regulations that inadvertently helped establish the foundation for China’s nearly perfect rare earth monopoly.

In the next installment of America’s Rare Earth Ultimatum, learn how a combination of regulations paved the way for Chinese dominance in rare earth mining, processing, and manufacturing.