Philanthropy

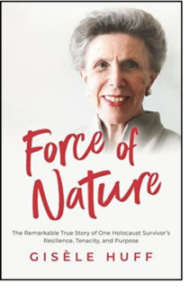

A conversation with Force of Nature author Gisèle Huff (Part 2 of 2)

As her memoir is released, the Holocaust survivor and philanthropy professional talks to Daniel P. Schmidt and Michael E. Hartmann about philanthropy and education reform, the need for reform of philanthropy itself, and the benefits of a universal basic income.

Gisèle Huff

Gisèle Huff

Gisèle Huff was 11 years old, on a ship arriving in New York Harbor at the end of a long trip from her native France, and—with tears of joy in her eyes—she looked up and saw the Statue of Liberty, a gift from France to the United States. In the decades since disembarking from that ship in 1947, her love for America has only grown—but she has great concerns about the country and its future. She’s also got some plans and proposals.

In her newly released memoir Force of Nature: The Remarkable True Story of One Holocaust Survivor’s Resilience, Tenacity, and Purpose, Huff compellingly describes that which preceded her trip to and those decades since her arrival in America, as well as that love for and those concerns about it.

Huff is president of the Gerald Huff Fund for Humanity, which studies and educates policymakers and the public about the benefits of a universal basic income. She founded the Gerald Huff Fund for Humanity after being executive director of the Jaquelin Hume Foundation, which had a strong program interest in education reform and is how we first met her. Earlier in her life, among so many other things, she ran for Congress and served in a development role for a private high school.

Few so well combine the warmth of spirit and cold analytic ability of Huff. She is fun and smart, passionate and principled, the “life of the party” and the spark of many debates.

She was kind enough to join us for a conversation last week. In the first of two parts of our discussion, which is here, we talk about her family history, education, and the American dream.

In the second part—the 20-minute video below—we discuss philanthropy and education reform, the need for reform of philanthropy itself, and the benefits of a universal basic income.

Schmidt and Hartmann (top row) and Huff (bottom)

After Huff moved to San Francisco, her first husband died of pancreatic cancer when he was 54 years old. “After that, I remarried and retired from my job as the director of development at a private high school,” she tells us.

“I was very bored,” Huff continues, and “I realized I was represented by Lynn Woolsey, whom I felt was much dumber than I am. Plato says we can’t be represented, governed by people who are dumber than you. So I decided to run for Congress just like that, and I was defeated in the primary.”

Huff learned that her friend Jerry Hume was looking for an executive director of the Jaquelin Hume Foundation. She was hired. During her 22-year tenure at the Hume Foundation, it pursued education reform, in the forms of both vouchers and charter schools, among other things.

“I got very frustrated, because it was glacially slow,” according to Huff. “I mean, the math didn’t work. We could be doing this for 100 years and we still wouldn’t have made a dent. And what was happening to children every day in America?”

Huff worked closely with Clayton Christensen as he formulated his thoughts about, researched, and wrote 2008’s Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns with Michael B. Horn and Curtis W. Johnson.

“Education in the 21st century is not the transfer of knowledge. The transfer of knowledge is in that little thing that I carry in my purse,” says Huff, pointing to her cell phone, “that has more knowledge than all of the teachers in America put together, where I can learn anything I want if I want to learn something.”

Governance mechanisms and curriculum content are not worth all the time, attention, and resources they attract, she believes. “There has to be a complete transformation of education,” she says.

Could philanthropy perhaps help fund that transformation? Philanthropy “is the ability to take lots of money out of the circulation of the economy and sheltered from taxes, and then spend it any old way you want, with a requirement that you spend five percent of the corpus yearly,” Huff tells us,

but the five percent includes expenses. So it could include a retreat for their staff to Cabo San Lucas, maybe two, maybe three, right? It means building what Gates has built—an entire complex of buildings. And that’s all included in the five percent … Building buildings is not a philanthropic activity.

***

Foundations are supposed to use this money for good purposes for the commonweal. That’s why they’re excused for not participating monetarily in the economy, right? … They don’t do anything innovative, ever. Ever.

She urges, “We have to make the payout 10% without expenses being allowed,” and “the foundation should sunset. There’s no reason why they should go on in perpetuity.”

After Huff’s son Gerald died in 2018—also of pancreatic cancer at the age of 54, as his father did—Huff founded the Gerald Huff Fund for Humanity to promote a universal basic income (UBI). A forward-looking technologist, Gerald Huff saw—and Gisèle Huff and the Huff Fund see—a UBI as a transitional solution to the existential threat of unemployment caused by technological advances.

Given the proposal’s universality, “everybody gets it and that’s the beauty of it,” Huff says. “That’s the sort of philosophical strength of this idea. Everyone is the same in the eyes of the consumer society …. It’s essentially saving capitalism. Capitalism depends on the flow, the circulation of money,” and a UBI would enable and continually facilitate that flow.

“When you look at the profits that are being posted this week by the huge corporations that are out of control, wild inflation is raging, and people can’t buy a dozen eggs,” she says, something is wrong with that picture. It’s an untenable situation.”

This article first appeared in the Giving Review on August 3, 2022.