Green Watch

Zoned For Homelessness

Without "Upzoning" Seattle's Head Tax will Fall Flat

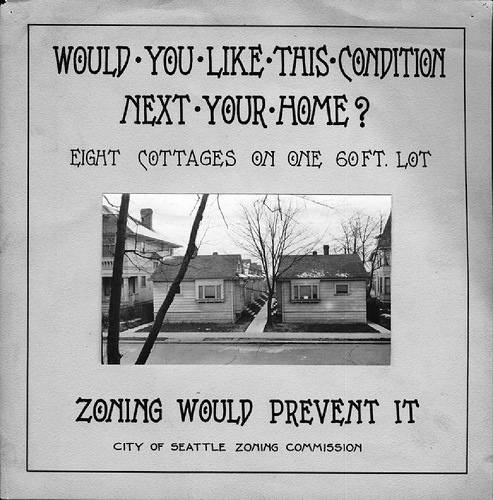

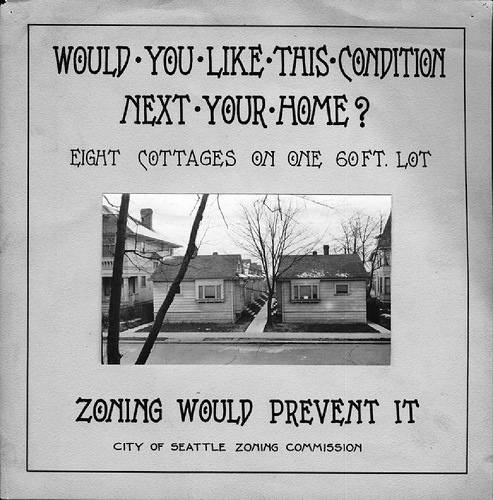

1922 Seattle Zoning Commission Poster from Seattle Archives

1922 Seattle Zoning Commission Poster from Seattle Archives

Even though Seattle passed a head tax—literally a tax on employees—on the top 3 percent of companies in the Emerald City, unions and activists think Amazon needs to be punished more. Working Washington, a collation of pro-labor groups funded by SEIU Local 775NW which argues in favor of unionizing the gig economy and recently won a victory for a $15 minimum wage, wrote to Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson, arguing that Amazon committed a felony by “intimidating a public servant.”

In case you missed it, after Seattle’s City Council proposed the tax, Amazon took action. It paused planning and construction on a new building, citing the tax as a reason for the online retailer to reconsider its future in the city. Predictably, it sent ripples throughout the country, especially for regions bidding to host Amazon’s new headquarters, HQ2.

It’s indicative of the debate that a company pausing to consider how to operate in the best interest of its employees and customers is viewed as “intimidating a public servant.” The proposed tax was originally estimated to bring in $75 million—the bulk of which would be siphoned from Amazon. The reduced tax will still bring in an extra $20 million. Don’t expect that companies like Amazon (or less controversial at the moment, Microsoft) will just absorb a loss of that magnitude. They will pass on such expenses to customers, who may choose to take their business elsewhere. It’s natural that Amazon would weigh the costs and benefits of continuing to operate in a city that’s become increasingly hostile to business.

Advocates of the tax note the importance of generating more revenue to address homelessness, a crisis which lawmakers declared a state of emergency in 2015. The city already earmarked $50 million to dedicate to homelessness. Despite this effort, homelessness is increasing, largely due to the city’s highly competitive housing market. Simply put, the rent is too damn high.

Homelessness and Affordable Housing

With the money it expropriates from its large employers, Seattle’s city government hopes to build more affordable housing. However, the city’s existing housing policies create a number of roadblocks that make both market-rate and subsidized housing construction inordinately difficult.

Since we’re talking about land, it’s worth considering the first axiom of real estate: location, location, location. Where will this new housing be built? Seattle has a number of neighborhoods zoned for only single-family homes, which take up more than half of the city’s land. Even if the city raises enough cash through the head tax to build the affordable housing it needs—far from a guarantee—it already is running out of locations to build that housing.

These zoning regulations don’t only hit the homeless and others at the bottom of the income and wealth bracket. Restricted housing supply also hurts taxpaying, working people (especially millennials) because the rules prohibit the construction of multi-family housing options (apartments and rowhouses) that young people often need as they move into cities and begin their careers. Younger people in Seattle want to see reforms to the zoning code that would allow for greater density—more multi-family options—in desirable areas, but incumbent interests oppose these “upzoning” efforts. In a nutshell, the housing market can’t solve the problem because demand is up and supply is kept artificially low.

The problem is exacerbated when you consider the homeless, who may struggle with a number of other issues including mental illness and addiction, a criminal record, chronic unemployment, or physical disabilities. If working millennials can’t convince Seattle neighborhoods to compromise on zoning, then how will the most vulnerable be welcomed in some of the Emerald City’s most desirable and least dense neighborhoods?

NIMBYs Resist Helping the Homeless

In the Magnolia neighborhood of Seattle, the drama is ready to play out for a second time. The neighborhood sits adjacent to Discovery Park and what remains of Fort Lawton, an abandoned U.S. Army Base. Most of the 534 acres of the base became Discovery Park, but 34 acres remain, populated by empty buildings and paved lots. Because the land was formerly inhabited by the federal government, Seattle could get the parcel for free if the city uses the land to build affordable housing.

Before the Great Recession, Seattle planned to do just that by building a mixed-income development—affordable housing alongside market-rate housing. But a “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) coalition of Magnolia homeowners stymied the plan. Fears about property values, public safety, “community character,” and environmental concerns for Discovery Park all coalesced in 2008 to prevent the city from developing the land. The Magnolia NIMBYs sued the city and used bureaucratic tactics like demanding environmental impact statements to prevent the project from moving forward. By the time the dust settled in 2010, the Great Recession had indefinitely postponed the development plans. The city is prepared to take up the cause again, but it’s clear officials don’t want to anger the neighborhood. A new proposal for the Fort Lawton site has less than half the planned housing proposed in 2008. Still, the neighborhood plans to resist construction.

Granted, this 34-acre plot will not solve the housing crisis on its own, but with the third-largest homeless population in the country, Seattle should be taking even marginal gains seriously. Lest the reader assume it is profit-hungry Republicans who object to building housing because they are afraid of homeless people, remember that every single Seattle neighborhood voted for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. In Washington’s 7th District congressional election, only Democrats were on the ballot; Republicans failed to even make it out of the state’s top-two primaries because the district leans so heavily Democratic. One would think that a city so populated with liberals (who pride themselves on their compassionate governance) would have no objection to creating more affordable housing. Unfortunately, the city’s liberal neighborhoods are contributing to the problems plaguing working millennials and the homeless alike.

There is a possible rezoning option that might not agitate communities made up of single-family homes. Rezoning Seattle’s industrial areas could ease the strain. The city’s strictly zoned industrial areas are full of empty buildings. Instead of reserving these areas for last century’s heavy industry, Seattle could encourage its large population of tech companies to use this industrial space by changing the city’s definition of “industrial.” Better yet, it could rezone these areas for housing as well.

Rezoning Would Be a Less Costly Fix

Without opening up Seattle to denser development, any revenue generated by the head tax will not alleviate the crisis. Short-term solutions won’t help the homeless long term; they need stability to get themselves on their feet and back into the workforce.

Furthermore, the hidden costs of the head tax may only exacerbate unemployment. If Amazon decides that Seattle isn’t the best place to do business, it could relocate to its future headquarters taking taxpaying employees and its tax-generating revenue elsewhere. If it does, it could send shockwaves through Seattle’s local economy which will suffer from its own loss of revenue. Amazon employs 40,000 people and its new building is expected to house another 7,000 employees. If instead, Seattle scares away the online retailer, the loss of tax revenue and jobs may reduce demand for housing, but the city’s supply of taxpaying citizens will also decrease, along with their income. Seattle should reconsider this gambit. It would be cheaper and easier to rezone areas and allow the housing market to self-correct.