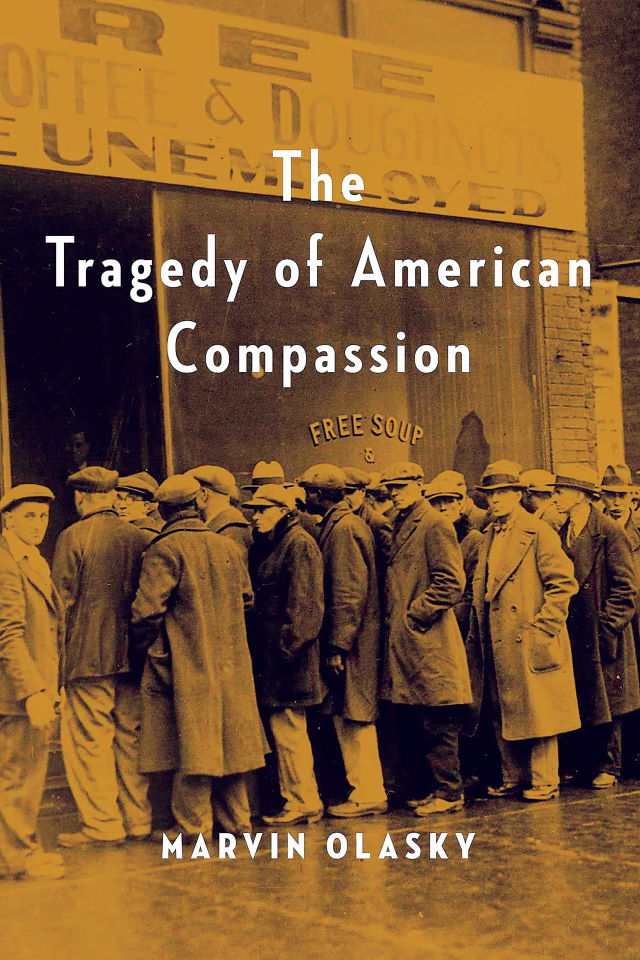

Book Profile

The Tragedy of American Compassion: Pilgrim Beginnings

Marvin Olasky is one of the conservative movement’s sharpest thinkers and most prolific writers. Credit: C-SPAN. License: https://bit.ly/3iydJAr.

Marvin Olasky is one of the conservative movement’s sharpest thinkers and most prolific writers. Credit: C-SPAN. License: https://bit.ly/3iydJAr.

Book Review: The Tragedy of American Compassion (full series)

Pilgrim Beginnings | Government “Compassion”

Marvin Olasky’s The Tragedy of American Compassion (Regnery, 2022) turned 30 last year. Three decades later it still stands as one of the most important books challenging modern America’s enormous welfare state, warranting an anniversary reprint and a fresh look by a new generation.

Olasky is one of the conservative movement’s sharpest thinkers and most prolific writers. Born to a Russian Jewish family in 1950, he converted first to Marxism in college, then the Communist Party in the early 1970s, and finally to Christianity in 1976, later becoming an elder in the Presbyterian Church in America. Olasky might be best known for his decades-long work at the Evangelical magazine World, which he left in January 2022 to become a senior fellow for the Discovery Institute, a think tank best known for its work on intelligent design theory.

At its core, Tragedy rejects the old liberal idea that poverty is the root of all social ills. Americans have spent countless trillions of dollars in government aid, only to find our cities are brimming with more indigence and addiction than ever.

Olasky recasts the tenets of welfare from “entitlement, bureaucracy, and secularism” (EBS) to “challenging, personal, and spiritual help” (CPS) rooted in the Bible’s understanding of charity. It launched a new era of books, articles, and fiery debate over the role of the government—and its oft-competitor, the church—in charity.

The first edition of Tragedy proved influential to the passage of bipartisan welfare reform legislation in 1996 and propelled Olasky into what he (almost bashfully) calls “an informal, occasional” advisory role for then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush (R).

Three decades later, Olasky has a few ideas of where to improve upon his original thesis. Nineteenth-century terms like “worthy poor,” which merely describe a biblical willingness to work, offended more often than edified. The collapse of American manufacturing, too, discouraged countless workers and amplified drug addiction across the Rust Belt.

Yet its central warning remains the same: All the money in the world cannot lift men out of the gutter. Reducing national poverty takes more than cold hearts and soft heads. Fortunately, Americans have an excellent model in our own country’s history.

Pilgrim Beginnings

The lesson begins in colonial America with William Bradford, head of Massachusetts’ tiny Plymouth Colony founded in 1620, who wrote of the Pilgrims’ tender care toward their sick and dying. Later, ministers across the 13 colonies made hospitality, discipline for children, and self-sacrifice central to their sermons. That sometimes meant withholding charity from those unwilling to work—not out of malice, as is often criticized today, but to correct sinful idleness. The goal was edification: turning the downtrodden into productive, Godfearing churchgoers.

This system worked because it emphasized personal responsibility, treated the family (rather than the individual) as the basic unit of society, and was rooted in the commandments and examples set by a holy, gracious God. It wasn’t perfect. But early America’s Christian—and particularly Calvinist—convictions made the nation famous for caring for its poor and “distressed” through hospitals, poorhouses, and schools.

Nationalizing Poverty

The incredible growth of American cities and immigration in the 19th century changed that. Observers pined for that old philanthropic spirit that had inexplicably dried up. Others petitioned the federal government to establish asylums for the mentally ill, the beginning of its long slide into welfare programs.

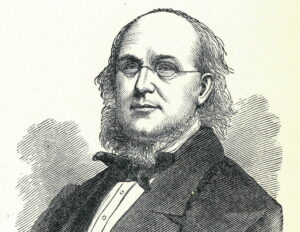

Universalist preachers such as Horace Greeley—better known today as a radical abolitionist—denied the doctrine of innate human sinfulness taught by their (orthodox) predecessors and began to advocate charity for even the able-bodied poor who refused to work. Across America, liberal and radical theologians founded communes free from private property and other “obsolete” assumptions. Civilization, not sin, was proclaimed the cause of all poverty. Men were naturally good but corrupted by bad institutions. They called their message the “Social Gospel.”

Universalist preachers such as Horace Greeley began to advocate charity for even the able-bodied poor who refused to work. Credit: Political Graveyard. License: https://bit.ly/3GVgR2x.

Socialism and Darwinism hit 19th century America hard. Socialism, a revolutionary import from Germany, threatened social cohesion and turned the problem of poverty into a class struggle to the death between rich and poor. The idea that wealth was not created, only stolen, burst violently into American cities and never left.

Many elites found validation of their own supposed superiority in Charles Darwin’s theory of human evolution—their success was unquestionably a product of natural selection, not chance or God’s providence. Who could argue with nature?

In the 1870s, New York City was crime-ridden to the extreme. Alcoholism, muggings, murder, and drug abuse—exacerbated by overcrowding in filthy slums—made the country’s cities practically unlivable. Even Horace Greeley complained in 1869 that “the beggars of New York are at once very numerous and remarkably impudent,” deciding that their only hope was to reform themselves or die.

“Social Darwinism” became the new religion of America’s aristocracy; eugenics—improving the populace through selective breeding—its sacrament. Social Darwinists blamed the rampant crime and mental illness in equal measure on biologically “unfit” immigrants and naïve Christians, who aimed to stave off welfare dependency by establishing thousands of new charities nationwide. And both Protestant and Roman Catholic missions answered the call—saving countless thousands from addiction, abuse, and damnation. Evangelicals founded the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and Salvation Army to encourage a strong work ethic based on biblical principles.

Yet the notion that the government should save the destitute through YMCA-style anti-poverty programs also spread rapidly. Professional social workers and federal regulations would do what volunteer Christians and heartfelt ministry did. Utopians even toyed with the idea of a “new man” perfected through scientific social engineering.

As Olasky puts it, “bad charity drove out good charity.”

In the next installment, the author explores the deadly effects of American “compassion.”