Philanthropy

The Red Cross Isn’t Doing Its Job in Natural Disasters

Image via News West 9, goo.gl/DFK2GC

Image via News West 9, goo.gl/DFK2GC

As Meagan Flynn in the Houston Press notes, a Texas woman’s Facebook post went viral when she complained that the Red Cross near Beaumont refused to distribute 400 hamburgers that had been flown in from Arizona to Havey victims because, according to the Red Cross, the victims had eaten peanut butter and jelly sandwiches a few hours earlier and didn’t need to eat any more.

At a Houston city council meeting, Councilman Dave Martin urged Houstonians to give their money and supplies to organizations other than the Red Cross, repeatedly calling it the “Red Loss,” saying it was the “most inept, unorganized organization [he’d] ever experienced.”

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey, many celebrities and journalists have slammed the Red Cross. Dan Gillmor, professor at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism took to Twitter to encourage his followers not to donate to the organization that many consider the leader in disaster relief efforts.

After actor and comedian Kevin Hart challenged fellow celebrities to donate to the Red Cross, actor and rapper Chris Brown (no stranger to controversy) donated $100,000 to Harvey victims, only after making it clear he had apprehensions about giving to the organization. Rapper T.I. however, was not as diplomatic. In a YouTube video he told Hart:

For the Houston Harvey challenge, I’ll dedicate 25K to it. But! You’ve got to find you an organization besides Red Cross. … F**k them and FEMA! No thank you!

The image of the Red Cross is tarnished more with each new natural disaster. ProPublica and NPR separately accused the Red Cross of deception after discovering it spends a quarter of donations just on fund raising, while actually spending 70 percent or less on disaster relief. The news outlets also found the organization poorly handled relief efforts after Superstorm Sandy, the Haitian earthquake, and the Louisiana floods.

The Red Cross’ track record during Irma proved to be no different. On Monday, Miami-Dade County and its school system blamed the Red Cross for the chaotic opening of storm shelters. With the lack of Red Cross workers that Miami needed, Mayor Carlos Gimenez had to send county police to open and maintain many of the shelters. County school chief Alberto Carvalho said,

In some instances, the Red Cross showed up very late. In some instances, the Red Cross never showed up. We made an executive decision that we would open the shelters on our own led by our principals and our custodians and our cafeteria workers.

This pattern of malpractice has even inspired a congressional report documenting the mismanagement and poor performance of the Red Cross. One of the most damning findings of the report confirmed the similar findings of Pro Publica and NPR. USA Today reports:

A study released last summer by Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, claimed the Red Cross had spent $124 million — or a quarter of the money donors gave after the devastating 2010 earthquake in Haiti — on internal expenses.

A History of Failures

As CRC Senior Fellow Martin Morse Wooster shows, since its Congressional chartering in 1905, the federal government has treated the Red Cross as the Fannie Mae of disaster relief. For example, in 2004, the Department of Homeland Security, made the organization the only nonprofit member of its National Response Plan. But the quasi-governmental status brings some of the deficiencies of big government—namely, the bureaucratization of the organization since it received its Congressional charter. Wooster writes:

Two of the leading books about disaster relief … were Edward T. Devine’s The Principles of Relief (1920) and J. Byron Deacon’s Disasters and the American Red Cross in Disaster Relief (1918). Both books came to strikingly similar conclusions. Deacon and Devine both argued that the very first step in a disaster relief program–before anyone was fed, clothed, or sheltered–was establishing a committee to determine who was in charge and what everyone’s task was. Deacon, for example, proposed a Central Committee that would oversee seven other committees, including an Executive Committee, a Finance Committee, a Committee on Relief Supplies and Warehouses, and a Committee on Relief and Rehabilitation. This was an age when social work was trying to become a profession, and both Devine and Deacon argued that only trained professionals, who would coolly sort the deserving from the undeserving, should aid disaster victims. “The first lesson” of disaster relief, Devine wrote, “is the folly and tastefulness of relying upon inexperienced, untrained, or incompetent agents for the distribution of relief.”

Wooster contrasts the disaster relief after the 1905 hurricane in Galveston, Texas, which claimed 6,000 lives and the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. In Galveston, Clara Barton oversaw the relief efforts of her American Association of the Red Cross. In less than two months, the organization completed its task and raised enough in private donations to promptly rebuild 1,100 homes. Barton also convinced farmers to send 18 million plants to help the Texas farmers back on their feet.

After Galveston, Barton was forced into an early retirement and the organization rebranded itself the American National Red Cross. When the San Francisco earthquake hit, the federal government donated $2.5 million to the new organization and President Theodore Roosevelt used the Red Cross as the army’s auxiliary. The city was placed under martial law, and after months and millions of dollars in donations, thousands of people still lived in shanties. This bureaucratic nightmare, meanwhile, produced long lines for basic necessities such as water, and victims experienced on average 43-day wait times for the Red Cross to process requests for aid.

What is striking however, is that before the Red Cross set foot on San Francisco soil, the city had already created its own nonprofit, the San Francisco Committee of Fifty, to deal with the earthquake, and its residents had already housed 300,000 homeless people on their own. Furthermore, city’s leaders resented Roosevelt for appointing the Red Cross to lead the cleanup efforts and naming it as a competitor for charitable donations. The San Francisco Chronicle even denounced the president “for insisting that the city could only be rebuilt through the aid of outsiders.”

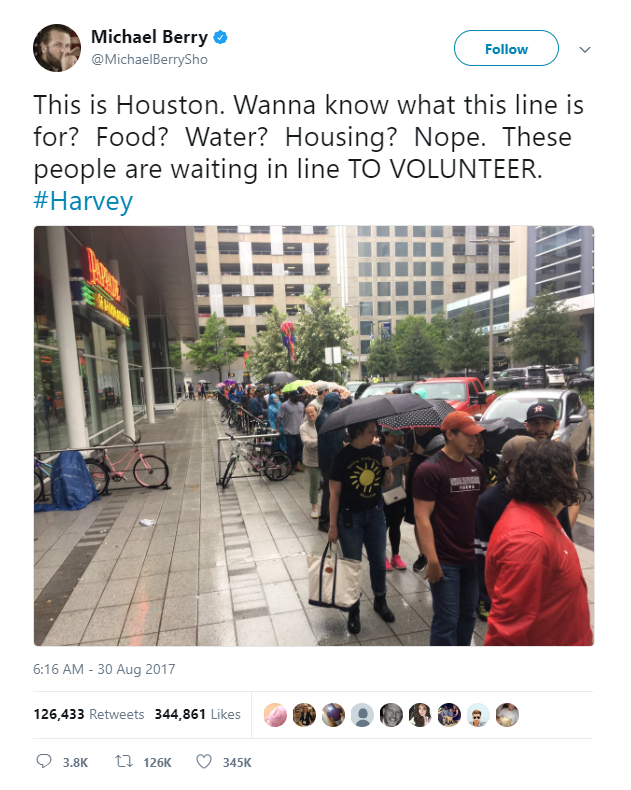

The outpour of generosity and volunteerism in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey has shown that local individuals and private charities often know best how to allocate resources after natural disasters.

Houstonharveyrescue.com is one example of local efforts to match rescuers with those in need without millions of dollars in overhead, or diverting needed resources for public relations performances. As of September 11, nearly 8,000 people had received help through its site, and this is only one of many volunteer-run efforts around Houston. (For more information about more successful philanthropic efforts, read this article from our Doing Good series.)

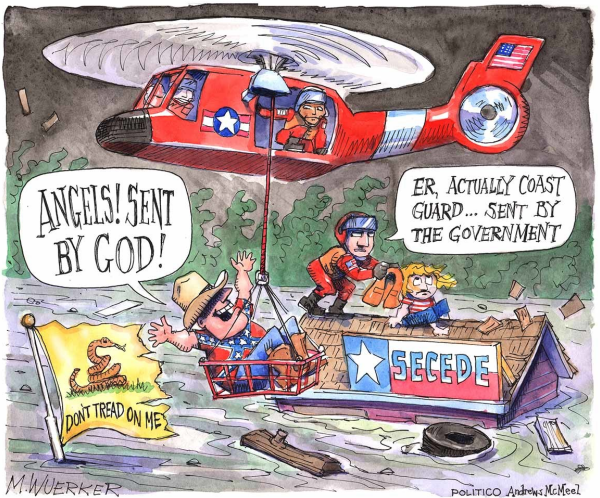

As Kemberlee Kaye notes, Politico and other coastal elites’ have attempted to characterize Houstonians as backwards ignoramuses whose go-it-alone efforts match their theories and prejudices more than their reality.

Image via legalinsurrection.com

But, she argues this is hardly the case and that “no one is looking for help from anyone other than their support groups or less affected neighbors willing to help.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkPx9KanzY8

Amazingly, the myriad examples of Red Cross mismanagement haven’t affected its ratings from some so-called nonprofit watchdog organizations. Charity Watch gives the Red Cross a B+ rating. Daniel Borochoff, the organization’s president and founder disagrees with people encouraging others to completely abandon the Red Cross. He instead argues that people should “give some to them for emergency short term needs, then give some to groups that are able to address longer term needs.”

The Red Cross is undoubtedly filled with many good people who want to help their fellow Americans. But, like many organizations given favored status by the government, it suffers from bureaucratic challenges absent in most private philanthropies and grassroots disaster relief groups.