Deception & Misdirection

NJ Redistricting Plan Too Partisan for National Democratic Redistricting Committee

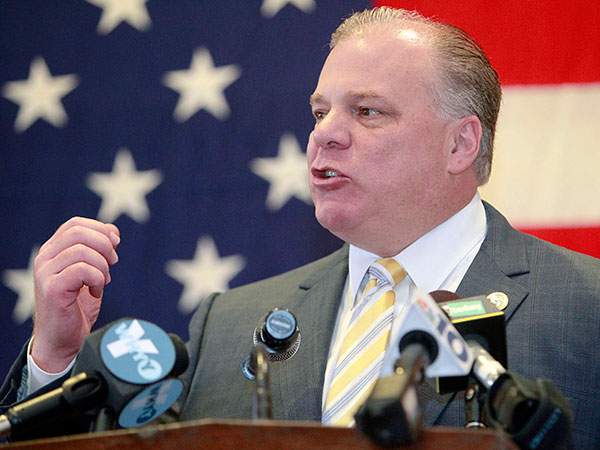

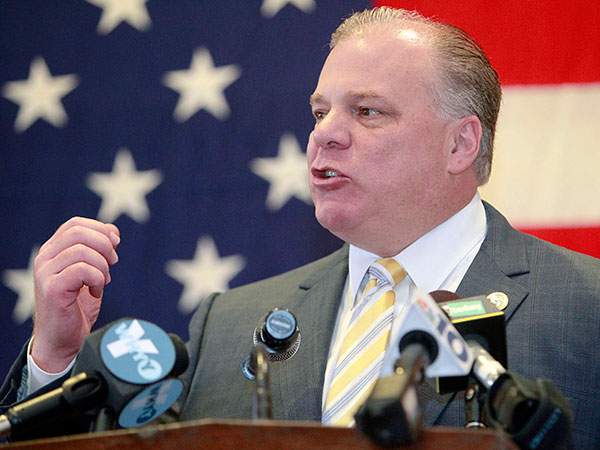

NJ Senate President Steve Sweeney makes a remark at the 119th Annual Labor Day Observance at Collingswood on Aug. 30, 2013. To help students afford college, NJ Senate President Steve Sweeney wants a commission to evaluate a number of options, including a "Pay Forward, Pay Back." ( File photo / AKIRA SUWA / Staff Photographer )

NJ Senate President Steve Sweeney makes a remark at the 119th Annual Labor Day Observance at Collingswood on Aug. 30, 2013. To help students afford college, NJ Senate President Steve Sweeney wants a commission to evaluate a number of options, including a "Pay Forward, Pay Back." ( File photo / AKIRA SUWA / Staff Photographer )

In the wake of bipartisan pushback, the New Jersey State Senate has tabled a vote on a proposed amendment to the state’s constitution which would have changed how the state conducts redistricting.

The Senate President, Stephen Sweeney (D), co-sponsored the controversial amendment. His plan would have put redistricting in the hands of voters through a ballot initiative. The problem? This seemingly small-“d” democratic measure would have entrenched a capital-“D” Democratic Party gerrymander.

Currently, New Jersey draws its districts with a bipartisan redistricting committee with 11 members. Members of each party choose five members each to sit on the apportionment committee. The eleventh member is appointed by the state Supreme Court, who presumably breaks ties between the parties.

Sweeney’s plan would have increased the size of the committee to 13 members, and give the state’s legislative leaders (senate president, assembly speaker, senate minority leader, and assembly minority leader) eight members of the redistricting committee. Of these members, four must be lawmakers and two must come from the public. More controversial though were provisions for how districts were to be drawn.

In drawing the district, the amendment would require the districts to be drawn according to recent statewide election results. Ten out of the 40 state legislative districts would need to be considered “competitive” for either party, but half of the districts would favor Democrats and half would favor Republicans.

This confusing formula is complicated by New Jersey’s demographics, which favor Democrats overall. Recent election results for President, U.S. Senators, and governor, would factor in the “fairness” of districts. Competitiveness would be described as:

. . . a district within five percentage points of the average district in the plan. For each competitive district in which a major political party’s percentage of total votes exceeds that party’s percentage of votes in the average district, there would be required to be a corresponding district in which that party’s percentage of total votes is less than the average district by approximately the same amount.

Complicated formulas and confusing statistics obscure the real point: a map drawn to these specifications would disproportionately favor Democrats, who already enjoy a trifecta in the Garden State’s government. (Trifecta refers to a single party controlling both houses of the legislature and the governor’s mansion.) In fact, the Princeton University Gerrymandering Project says that such a plan could convert “57% of statewide popular support into 70% of seats,” and that “Democrats could even retain their majority in the Assembly with as little as 45% of the statewide vote.”

As CRC has reported, retaking control of redistricting has been a top line priority of the Democratic Party since at least 2010. But Sweeney’s plan was so brazenly partisan that even former Attorney General Eric Holder, the chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), opposed the New Jersey plan. NRDC is on the front lines of introducing Democratic gerrymanders through litigation and court-ordered map-drawing. The fact that the hyper-partisan NDRC is distancing itself from Sweeney’s plan is a sure sign that the proposed amendment was beyond the pale—even for partisans such as Holder and the Democrats’ go-to lawyer, Marc Elias.

But then Sweeney’s record shows him to be a partisan seeking to grab power and influence wherever he can.

Despite controlling New Jersey’s government and serving as president of the state senate, Stephen Sweeney has attempted to seize more power—for himself first, and his party second. His inconsistent record on labor and taxes blemishes his liberal bona fides and reveals his opportunism.

While Republican Chris Christie occupied the governor’s mansion, the New Jersey legislature passed a bill that would place millionaires in a new tax bracket, taxing them at an obscene 10.75 percent (that’s on top of federal taxes and the highest average property taxes in the nation). Christie vetoed this measure five times since 2010. But New Jersey elected Democrat Phil Murphy in 2017. It should have been easy for Sweeney to send this bill to Murphy, who endorsed such a tax.

But in a shocking turnabout, Sweeney parted ways with Murphy, saying in February, “It’s the absolute last thing that I’m willing to look at.” Of course, Sweeney blamed tax reform at the national level (which curtailed the “State and Local Tax” [SALT] deduction that taxpayers in high-tax states like New Jersey use to partially offset their high state taxes) for his change of heart; however, it is not uncommon for politicians to back away from radical reforms once political office is secured. (Look no further than the 115th Congress, where Senate Republicans balked at repealing Obamacare and House Republicans did not even try to pass a balanced budget.)

Sweeney also drew the ire of former Assembly Majority Leader and New Jersey Democratic Party Chair, U.S. Representative Bonnie Watson Coleman, who currently represents New Jersey’s 12th Congressional District. Rep. Coleman sent a letter to the senate president, urging him to halt his power struggle with the governor, lest it hurt the state Democratic Party.

Surely, though, Sweeney, the fourth vice president of the International Association of Iron Workers Union (a day job for which he is paid $202,801 in annual salary as part of total compensation and expenses of $240,730, according to the most recent federal disclosures) would be a consistent ally of Big Labor. And usually he is—especially when benefits for his own building trades are on the line: In 2002, Sweeney backed a provision to promote project labor agreements—which guarantee union-level wages and all but guarantee unionized workers on public works projects—with state and municipal governments.

However, when other factions of Big Labor are in the cross-hairs, Sweeney is less loyal. In 2011, Sweeny teamed up with then-Governor Chris Christie to pass a pension reform hated by New Jersey’s government worker unions, especially the teachers’ union. The reform required state workers to pay more for pension and health benefits in order to ensure the state was able to fully fund the pension system, which had been underfunded for years. While a smart fiscal move, slow growth in New Jersey’s economy meant the state failed to make payments to the pension fund.

For this betrayal, Sweeney was repaid by the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA)—the state’s largest teachers union. In 2017, NJEA, through its political activism committee, Garden State Forward, spent nearly $4.7 million failing to unseat him.

If Sweeney thought his gerrymandering power play was going to earn him points from the Democratic National Committee, he was sorely mistaken. After two public hearings which drew more opposition than support, Sweeney opted against bringing the proposal to a vote. This is good news for New Jersey’s Republican voters, and for its Democrats. After all, gerrymanders aren’t forever and such a plan could easily end up biting Democrats if the demographics change quickly. Until then, it’s safe to say that such plans are ill-advised, even for the partisan groups seeking to draw favorable maps.