Labor Watch

Lessons in How to Run a Congressional Investigation from Bobby Kennedy

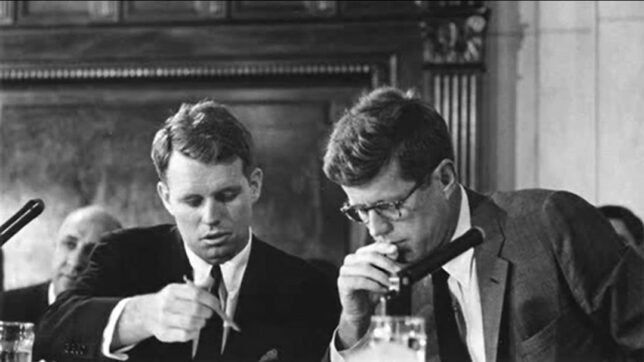

Robert F. Kennedy (left) and Sen. John F. Kennedy (D-MA) (right) at a McClellan Committee meeting. Credit: JFK Tapes/YouTube.

Robert F. Kennedy (left) and Sen. John F. Kennedy (D-MA) (right) at a McClellan Committee meeting. Credit: JFK Tapes/YouTube.

As the 118th Congress’s House of Representatives gets off to its stuttering start, the new majority Republicans are eager to pursue all manner of investigations into potentially corrupt activities by the Biden administration and its institutional liberal allies. Skeptics look at the past, like efforts by the current majority’s counterparts during the Obama administration, and see a certainty of disappointment. Regardless of whether the investigation’s targets have done anything wrong or embarrassing, Congressmen will strut before the C-SPAN cameras in a ritual dance worthy of some puffy-chested seabird and achieve little.

But let’s assume that the new House Republican majority genuinely wishes to put in hard work and conduct meaningful congressional oversight with more of a payoff than higher contributions to their reelection campaigns on WinRed (the GOP’s counterpart to the ActBlue small-dollar fundraising machine of the Democrats). If that is the case, they could do worse than take lessons from one long-ago Democrat: Robert F. “Bobby” Kennedy Sr. who served as U.S. attorney general during his brother’s presidency and as a U.S. senator from New York.

Uncovering The Enemy Within

From 1957 until he left to aid his brother’s presidential campaign in 1959, Bobby Kennedy was chief counsel to the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, known as the McClellan Committee after its chairman, U.S. Sen. John McClellan (D-AR). That committee was of great consequence: Its efforts led to the retirement of Dave Beck, head of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters; set the stage for further legal prosecution of Jimmy Hoffa, Beck’s successor as president of the Teamsters; exposed corruption in other labor unions that were compromised by corrupt leadership; and laid the groundwork for the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959.

So, in 1960, surely only coincidentally during his brother’s presidential campaign, Kennedy published a memoir of his time on the McClellan Committee. Titled The Enemy Within, Kennedy’s book told the story of how he gathered a team of investigators to chase after the corrupt figures who ran what was at the time America’s largest union, the gangsters who surrounded large sections of the labor movement, and the management consultants and business figures who aided the kleptocratic union bosses. The book tells more than just history; it also shows how a serious congressional investigation can be run.

Keep Legislative Goals in Mind

Article I, Section I, of the U.S. Constitution lays out the purpose of Congress: “All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” The powers of congressional committees derive from the legislative power—the power to devise and propose new laws and scrutinize the administration of existing laws, action necessitated by Congress’s habit of passing legislation that grants large discretionary powers to the executive branch.

Kennedy’s investigations led to legislation: the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 (LMRDA). Elements of the legislation responded directly to misconduct uncovered by the McClellan Committee. The corruption of management-side consultants like Nathan Shefferman, a fixer for Teamsters boss Dave Beck and employers in the trucking industry, led to reporting requirements. The discovery that large numbers of Teamsters officials had criminal records led to a time bar against ex-cons serving in union office. The abuse of local union trusteeships by corrupted national unions (especially the Teamsters) led to government regulation of such trusteeships. And dubious-to-nonexistent financial recordkeeping at many unions led to the mandate that unions file annual financial reports with the U.S. Department of Labor.

In all these cases, discoveries made during the investigation led to proposals for legislative correction, which were ultimately adopted in LMRDA. As important as nailing crooks was to Kennedy’s team—in his concluding writing, Kennedy claimed “more than twenty” had been convicted as a result of McClellan Committee–related investigations—the committee’s work still led to legislation.

Assemble the Right Team

While memoirs are notorious for embellishing the reputations of their authors and their authors’ allies, the results of Kennedy’s and his team’s work speak for themselves, even over 60 years later. But the McClellan Committee staff investigators were in many ways a cut above the usual cast of younger political careerists (or would-be careerists) who ordinarily populate congressional staff. Perhaps most prominent was Carmine Bellino, the experienced forensic accountant who had aided Kennedy’s investigative work for prior Senate committees. And Cye Cheasty, a private investigator turned double agent, would have put Hoffa in jail if not for prosecutorial bungling and jury nullification.

Indeed, Kennedy discusses with barely concealed partisan mirth the travails of the committee’s minority Republican staffers, who had been tasked by senators’ agreement to conduct the inquiries into the United Auto Workers led by Walter Reuther, after press speculation that Reuther had been exempted from the committee’s scrutiny during an ongoing labor dispute in Wisconsin because he was aligned with the Democratic Party. (The Teamsters, who had been the focus of the most scrutiny, at the time frequently aligned with the Republican Party. The union has not done so since the 1980s, despite repeated GOP efforts to court it.) Kennedy’s team inquired into the labor dispute and found no evidence of corruption beyond some strike violence, with apparent financial irregularities that were flagged by the Republican staff as having innocuous explanations. The result was a hearing in which Reuther was able to grandstand over the Republican senators, a complete failure of the party’s political aims.

Present the Evidence Smartly

The McClellan Committee’s legislative aims were boosted by a series of televised hearings, at which union bosses, gangsters, business consultants of dubious ethics, and other witnesses were brought before the senators and Chief Counsel Kennedy to answer questions. And they often pled the Fifth Amendment. In his memoir, Kennedy wrote that people would ask him why he would ask publicly questions of witnesses to which he appeared to know the answers.

Kennedy wrote in response that he thought it would be unfair for him or his investigators to present simple hearsay (“person x told me . . .”) rather than calling a witness to answer himself, and also that a witness taking the Fifth (Kennedy specifically mentions Teamster boss Dave Beck’s invocation of his rights) provides the public and Congress with “important information.” Beck’s invocation of the Fifth led to the adoption of an AFL-CIO rule forbidding union officials’ pleading the Fifth on pain of resignation or their union’s expulsion from the federation that lasted until the federation’s then-secretary-treasurer Richard Trumka, later AFL-CIO president, invoked his rights in an investigation (coincidentally, into the Teamsters) in the late 1990s.

By doing the legwork to discover information before bringing public figures before the public spotlights, the McClellan Committee was able to maximize the impact of dramatic scenes such as Beck’s taking the Fifth. Serious investigation and serious questioning is the only way to make the legislative cases a public hearing would hope to make.

Conclusion

Congressional oversight hearings usually promise more than they can deliver. Not everyone’s political opponents are as clearly corrupt as Bobby Kennedy’s nemesis James Riddle Hoffa. But by taking lessons from history, congressional investigators can avoid the pitfalls of other attempts at accountability that were far less successful than the McClellan Committee. Perusing The Enemy Within would be far from the worst place to start.