Book Profile

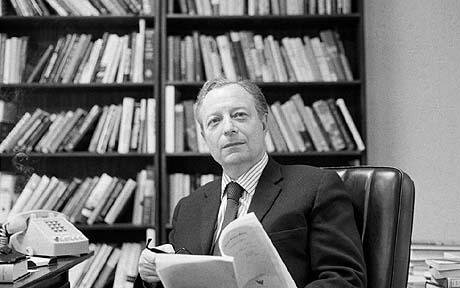

Irving Kristol: A Good Egghead, Messily Making Omelettes

More of Irving Kristol’s kind of counter-establishment insurgence, as described in Michael J. Brown’s new book, might now be needed again—including in philanthropy.

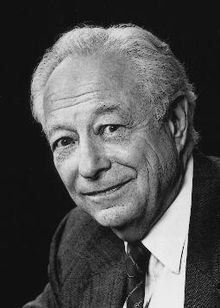

Irving Kristol

Irving Kristol

Michael J. Brown’s interesting new book Hope & Scorn: Eggheads, Experts & Elites in American Politics profiles prominent public intellectuals in American life and their shifting relationship with, and role in, politics and policymaking. His thoughtful, and thought-provoking, chapter on one of them in particular—Irving Kristol, the “godfather of neoconservatism”—is fittingly entitled “The Intellectual Against Intellectuals.”

Brown is an assistant professor of history at the Rochester Institute of Technology. His Hope & Scorn treatment of Kristol helpfully shows why the country, and conservatism, needs a little more thought leaders like him, and more counter-establishment insurgence like his, now. Helpfully, and perhaps timely.

Kristol was very much an egghead himself, yes, as Brown tells it. Kristol was more than willing to metaphorically “break some eggs,” however—to argumentatively, but good-naturedly “crack some heads” and messily “make omelettes” in the sometimes-heated kitchen of public discourse. A timely telling, since so needed now—in many contexts, perhaps including the philanthropic one, with which Kristol was intimately familiar.

“[F]ew individuals have influenced the flow of so many dollars to so many scholars, projects, and institutions, with such a profound impact on the course of American public policy,” as the Hudson Institute’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal noted for a panel discussion and reminiscences about Kristol and his role in philanthropy after his death in 2009.

Characterizing, Confronting, and Countering

Kristol was a New York University professor; a founder or co-founder of Encounter magazine, The Public Interest, and the Institute for Educational Affairs (IEA); a prolific contributor to those and several other publications; and an American Enterprise Institute fellow.

Kristol (Wikimedia Commons)

In Hope & Scorn, Brown well-describes Kristol’s analysis of and animating concern in the 1970s about a “New Class associated with media, government, nonprofits, and universities” that “was gaining unprecedented influence in a post-industrial society where knowledge was becoming capital. From powerful positions in the state, the culture, and the information economy, these intellectuals could subject Americans to increased regulation and even ideological conversion. They could transform the nation’s politics and culture, ‘subverting’ its civilization.” (All endnotes omitted.)

Brown then outlines Kristol’s actions to prevent any such subversion. “Confronting the New Class required resources: a ‘counter-establishment’ of think tanks, journals, and academic posts. Kristol was at the center of this effort,” according to Brown. “He fought the New Class on the intellectual plane and the solid ground of institution building.

“Characterizing the New Class as intellectuals, Kristol railed against them,” Brown notes. “Yet Kristol was himself an intellectual . . . .” Kristol made others’ previous thought about a New Class or its equivalent “more polemical, wove it into cultural and political elements unfolding in the Nixon years, linked it with postwar American conservatism, and, finally, responded to it with a potent program of intellectual activism.”

Ideas and Institutions, in That Order

The egghead Kristol’s success can be credited to his substance, strategy, and style. His omelette became quite a soufflé, actually. He “was building a circuit between the intellectual world, the business community, and the center of political power,” Brown writes. “It was a circuit through which a current of ideas and ideologues would flow, powering a rightward surge that culminated in the presidency of Ronald Reagan and in a legacy of neoconservative institutions, outlooks, and policies.”

“It is the self-imposed assignment of neoconservatism to explain to the American people why they are right, and to the intellectuals why they are wrong,” Brown quotes Kristol as putting it. “The first link in Kristol’s logic was his premise that the conflict of the 1970s,” according to Brown, “would occur on the plane of ideas.” (Emphasis in original.) The logic’s next link: “[i]f ideas were the crucial front, then exponents of ideas, the New Class, were the crucial people,” explicitly including foundation staffs.

Kristol urged business executives “to think strategically about philanthropy,” Brown writes. Too much corporate money, Brown quotes Kristol, goes to “foundations and universities . . . populated by those members of the ‘new class’ who sincerely believe that the larger portion of human virtue is to be found in the public sector, and the larger portion of human vice in the private.”

Kristol argued funding should flow elsewhere, and had an idea of where. “Well, if you decide to go exploring for oil, you find a competent geologist,” Brown quotes Kristol. “Similarly, if you wish to make a productive investment in the intellectual and educational worlds, you find competent intellectuals and scholars—‘dissident’ members as it were, of the ‘new class’—to offer guidance.”

Kristol always offered such guidance, including through IEA, which started in 1978. IEA’s initial slate of board members included John M. Olin Foundation president William E. Simon; media executive Frank Shakespeare, who later served on The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation’s board; and theologian Michael Novak. IEA’s staff was headed by Michael S. Joyce, who later became executive director of the Olin Foundation and president of the Bradley Foundation.

“For Irving, it was always: Here’s the problem, here’s what we might do about it,” Joyce wrote in “The Common Man’s Uncommon Intellectual,” his contribution to 1995’s The Neoconservative Imagination: Essays in Honor of Irving Kristol. “[N]o element of Irving’s work,” Joyce notes, “has been more enlightening or instructive than his subtle, nuanced teaching about the virtues and vices of the everyday bourgeois citizen.”

Led by Kristol, “So long as they wrote and criticized, the neoconservatives displayed a kind of practical wisdom,” according to Edmund Fawcett in his new book Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition. “Yet they remained intellectuals, concerned above all to fight other intellectuals.”

The Benefits of Dissidence, and Dissidents

American public life’s coming years will likely feature many fights—hopefully, much of it to ultimate good effect for everyday citizens. We could see, for example, an insurgent politician against the politicians. Or maybe some new, younger-led, preferably tradition-respecting and historically informed institutions against established ones. Perhaps academics against the academy, as Kristol encouraged. Maybe grassroots activists insurgently against well-credentialed elites. Working-class union members against Big Labor. Middle-class entrepreneurs against the too-many excesses of crony capitalism and Big Business. On and on.

There has been for a long time and remains an excess of eggheads, experts, and elites in and around American establishment philanthropy, too. As Brown’s Hope & Scorn shows, Kristol was one of them—insightfully offering wisdom, guidance, and advice to conservative grantmakers and shaping conservative grantmaking, including to dissident intellectuals. As Kristol was an “intellectual against intellectuals” who greatly benefited the country, and conservatism, we may all prospectively benefit from any dissident philanthropy against philanthropists, as well.

This article first appeared in the Giving Review on October 28, 2020.