Organization Trends

Independent Redistricting Commissions Are Problematic, Says . . . the New York Times?

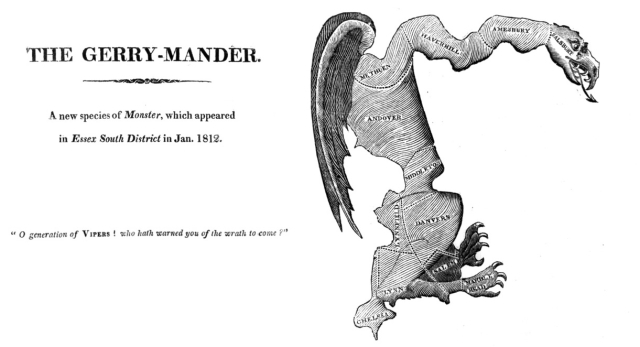

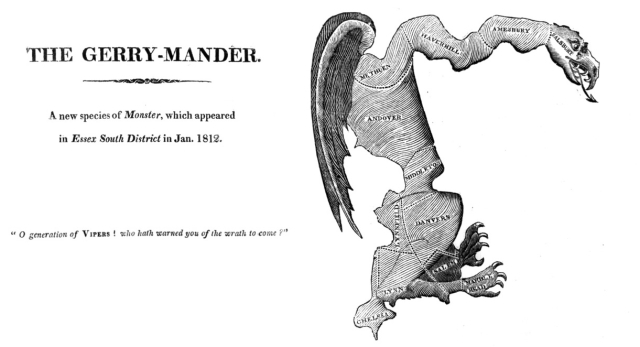

The original gerrymandered district in Massachusetts as caricatured as a dragon in a political cartoon from 1812. License: Public domain.

The original gerrymandered district in Massachusetts as caricatured as a dragon in a political cartoon from 1812. License: Public domain.

Readers of the Capital Research magazine (back issues here) will be familiar with the drawbacks of independent redistricting commissions. In the May/June 2021 issue, I wrote extensively on how commissions fail to generate maps more proportional to state-level partisanship than traditional legislative redistricting. In fact, commissions can structurally ensure de facto partisan gerrymandering behind closed doors and can be captured by special interests.

Recently, readers of the New York Times learned what readers of Capital Research already knew.

A “Cure” Worse Than the Disease

Start with the headline: “How a Cure for Gerrymandering Left U.S. Politics Ailing in New Ways.” Liberals, led by political groups like Michigan’s Voters Not Politicians, pushed “independent redistricting commissions” to take redistricting power from state legislatures. This would supposedly “cure” the practice of political actors drawing congressional and legislative districts to advantage themselves.

Now, readers of Capital Research Center’s magazine and our report “The Myth of Non-Partisan Districts” would doubt that the practice of political actors drawing congressional and legislative districts to advantage themselves could possibly be cured. Lo and behold, the Times now observes, “In state after state, the parties have largely abdicated their commitments to representative maps.”

As We Have Observed

The Times also discovered what Capital Research readers already knew about the fail-harm structure of many redistricting commissions and the partisan backing these supposedly neutral panels received:

For decades, well-meaning people saw independent commissions as a crucial way to eliminate gamesmanship that exasperates many voters and distorts American politics: the incumbency protection, the devaluing of people’s votes, the polarization and stridency that it all fuels.

As a supposed fix, the independent panels were never entirely insulated from politics. The changes were often supported by Democrats, who felt overmatched by Republican majorities in statehouses and by G.O.P.-drawn maps that seemed to set those partisan tilts in stone.

Anyone who followed the Arizona and California redistricting after the 2010 Census—like our readers—already knew this. In California, as no less a liberal outlet than ProPublica reported, organized liberal interest groups aligned with incumbent Democratic representatives to lobby the commission to interpret “communities of interest” in the manner most favorable for those incumbents.

Arizona’s commission, structurally designed in such a way that it could become the personal fief of a closeted partisan “independent” member, drew the “Mathismander,” a Democratic-gerrymander map named for the chair of the commission that produced it. The map yielded seat-majority/state-level “popular vote” splits favoring Democrats in two of the five elections that used it.

A Conversion of Convenience

But I cannot help but question the timing of the Times’s revelations. The Times discovered the drawbacks of redistricting commissions during an election cycle in which the adoption and activities of commissions may be a drag on Democratic prospects rather than Republican prospects. California’s commission is still likely to draw a disproportionally Democratic map, but the new commission in Colorado—a Democratic trifecta state that could have gerrymandered aggressively but for the commission’s adoption—drew a reasonable proxy for a proportional outcome. Arizona will likely replace the Mathismander with a map less favorable to the Democratic Party. Virginia, which before its 2021 state elections was under a Democratic trifecta that could have rush-gerrymandered the state, will see maps drawn by state courts.

And closest to the Times’s home, Democrats in New York State have large enough majorities to override any map adopted by the state’s redistricting commission, even though their campaigns to lower the override threshold failed in early November. As the Times has conveniently discovered, the only law of redistricting remains Barone’s Law: “All process arguments are insincere, including this one.”