Foundation Watch

Ford Abandons Detroit: Funding Counterproductive Initiatives in Michigan

Ford Abandons Detroit (complete series)

Falling out with the Family | Forgetting its Roots | Funding Counterproductive Initiatives in Michigan

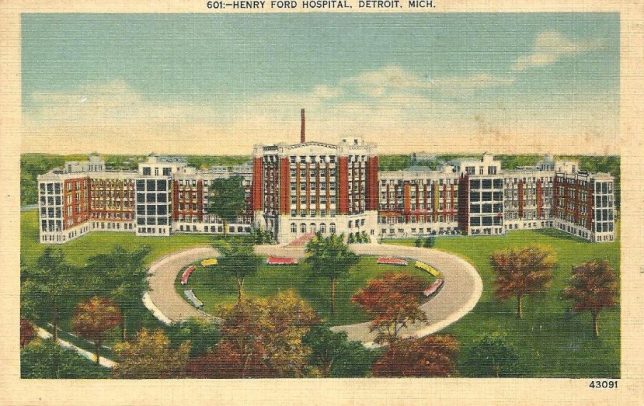

Summary: The second largest philanthropic foundation in America emerged in the Motor City. The Ford Foundation was the legacy of one of America’s most famous entrepreneurs—Henry Ford. After giving rise to a booming industry, Ford decided to make provisions for his home city by establishing a charitable foundation and building a hospital. But future generations of trustees ignored his vision for the foundation he endowed. The city that was once the crown jewel of American Industry declared bankruptcy and is rusting away as the Ford Foundation spreads its wealth among progressives whose pet projects only promise to exacerbate the problems plaguing Detroit and Michigan.

Spending Money on Groups That Want to Spend More Money

Nearly $2.4 million of that $50.2 million in left-wing advocacy was directed at Michigan. As Henry Ford II complained 45 years ago, this was a giving agenda that didn’t show an appreciation for competitive enterprise:

$180,000 for the Michigan League for Public Policy. The MLPP is a reliable supporter of larger government and more state spending, advocating recently for a higher minimum wage and against a broad-based tax cut signed by Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder.

$1,400,000 for State Voices. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., this advocacy organization partners with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and others with a left-wing policy agenda. It received two Ford Foundation grants in 2015 that were earmarked to be spent in Michigan on state budget projects, political redistricting, and other work favoring the agendas of Democrats and proponents of higher state spending.

$350,000 for Progress Michigan Education. Progress Michigan is a partisan communications pit bull advocating for left-wing policy and political outcomes, not necessarily related to education. Recent news releases have included several criticisms of the Republican nominee for governor over his policies regarding state-mandated overtime expansion and the energy industry. These releases also include denunciations of the Republican-led Michigan Legislature for failing to defend ObamaCare and passing state budgets that spend too little.

$425,000 for the Restaurant Opportunities Center United. Despite not registering as a labor union, this organization behaves similarly. Its policy agendas include advocating for a higher minimum wage for restaurant workers and launching public relations offensives against the National Restaurant Association.

The last thing Michigan employers and employees need is to pay for a more expensive and intrusive state government.

Most of the nation considers the 2008 financial crisis the start of a serious recession, but Michigan got a big head start on the hard times. The state’s unemployment rate in January 2001 was 4.4 percent, roughly equal to the national average. By January 2008, before the financial crisis began in earnest for the rest of America, Michigan had already lost more than 330,000 jobs and had a 7.1 percent unemployment rate.

And then came the automotive industry bankruptcies and the full force of the financial crisis. By January 2010, the Michigan unemployment rate had zoomed to 13.9 percent, and total job losses since 2001 had exceeded 760,000.

It’s difficult to exaggerate the economic magnitude of this: West Virginia—the 38th largest U.S. state by population—doesn’t even have 760,000 jobs.

Even today, with the unemployment rate back down to 4.3 percent and a sense of economic optimism returning, Michigan still has 250,000 fewer jobs than it did nearly 18 years ago.

Meanwhile, the nation as a whole has 13.5 million more jobs than it did back in January 2001. Even with the most generous of policy welcome mats laid out for entrepreneurs, Michigan’s economic scars from “the lost decade” will require a generation to fully heal.

Increasing the price of hiring people (a higher minimum wage) leads to fewer jobs, and more government spending crowds out private sector spending. Michigan needs none of this nonsense. There may be states where the Ford Foundation’s left-wing economic policies could do more damage. . . but not many.

What If?

The front page of the Detroit News for November 22, 1963, carried both tragedy and comedy. The obvious tragedy was as big as the font it was written in: “KENNEDY DEAD.”

The comedy was along the left side in smaller print: “Ford Buys Lions.”

That would be the Detroit Lions. William Clay Ford, Sr., grandson of the Ford Motor Company founder and younger brother of Henry Ford II, would own the National Football League’s most uncompetitive enterprise until his death almost 51 years later. It would be 28 years before they won him his one and only playoff game. Millions of local fans born after 1963 learned to tell non-Michiganders “We don’t watch professional football on Sundays . . . we watch the Lions.”

If the owner of the team was as disgusted with its performance as his brother was with the Ford Foundation, he rarely, if ever, showed it. Yet ask a typical Michigander today to name a failure of the Ford family and the Lions will easily top the list, perhaps even stand alone on the list. Few would or could name the Ford Foundation and how it disappointed the last of the Fords who had any control over it.

The history on the Foundation website reports differently: “Henry Ford II remained a key figure in the foundation, serving as president and as chair and member of the board of trustees and overseeing its transformation from a local Detroit foundation to a national and international organization.”

To imply Henry Ford II willfully turned the Ford Foundation into what it has become is—to put it charitably—very misleading. To be more honest about it would be to say he died in 1987 regretting the outcome they credit him with creating.

“I made a big mistake on the Ford Foundation,” said Henry II on a 1980’s audio in the possession of the Henry Ford Museum. He continued, “I was young, inexperienced, and stupid. I just muffed it. It got out of control and stayed out of control. And now it’s gone, of course.”

In 1978, shortly after resigning from the Foundation’s board, he told a New York Times reporter that he’d have made a radically different decision if given the chance at a do-over:

What I would have loved to have done is split the foundation into three parts—give one-third of it to the Henry Ford Hospital, one-third of it to [what are today known as the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village], and the other third would have stayed as part of the Foundation. But [it would have been] one-third as big and therefore wouldn’t have gotten into so many different kinds of things . . .

His words and deeds conclusively demonstrate Henry II wanted the majority of his grandfather’s fortune spent in the region where it was created and on the principles that made it possible.

The “what if?” discussions are almost too painful to contemplate.

Prior to being surpassed in net assets by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Ford Foundation was, for a long time, the wealthiest in America. Today, it remains the second largest and gives away more than half a billion dollars annually.

It’s obvious that taking so much of that private fortune away from Detroit and Michigan for so many decades did those economies no favors. It’s also a bitter irony at best—and blatant hypocrisy at worst—that those running the Foundation have been using it as a cash cow to support big government spending policies that would impose a heavier burden on the private sector that remains in the region.

It’s impossible to imagine many billions of dollars in additional Ford money coming back home over the last sixty years—building up and maintaining fantastic hospitals, schools, cultural institutions, and much else—and not see a much healthier Great Lakes State.

There are lots of villains—individuals, attitudes, institutions, and policies—that receive and richly deserve the blame for Detroit’s decline. The Ford Foundation is usually absent from that dishonorable roll call, but no less deserving of shame.

Similarly, those of us who share Henry Ford II’s appreciation for free enterprise and free society solutions can imagine a much better world if so much of that money had been spent promoting his principles, rather than opposing them.

Would Michigan by now have an education system that gave parents the ability to choose the individualized schooling that best suits each of their children?

Might we have by now a low cost, high quality healthcare system driven by consumers in charge of their own money, rather than big government and near-monopoly insurance bureaucracies in bed with big government?

Might the successful promotion of free enterprise policies produce an economy that built on the success of entrepreneurs, giving rise to several foundations with fortunes in excess of the one Henry Ford left behind, each virtuously reinforcing the capitalism and hometowns that made them possible?

In that 1978 interview with the New York Times, a frustrated Henry II offered one more idea, saying it would be “O.K. by me” if the Ford Foundation would just quickly “spend its way out of existence.”

Regretfully, yet another example of why it is too bad the “Deuce” didn’t get his way.