Foundation Watch

Charitable Infidelity: How Best to Give?

Charitable Infidelity (complete series)

How Best to Give? | Providing Clear Intent | Are DAFs Secure for Ideological Giving? | Donor Beware

Summary: The American people are some of the most generous in the world. According to Giving USA, Americans gave an estimated $390.05 billion to charities in 2016 alone. But even as charitable giving grows, philanthropy itself is changing, thanks in no small part to the rise of donor-advised funds. But what are these funds, and what opportunities—and dangers—do they present to conservative donors?

What is a philanthropist? The answer might depend on who you ask—and when. A century ago, the average American donor resembled John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, or Andrew Carnegie: fabulously wealthy captains of industry whose fortunes built the grand philanthropic projects that bear their names today, such as Carnegie Hall in New York City. But today, philanthropists look much more like your grandparents, parents, or even the Millennials in your life.

Philanthropy is changing—not only how we give, but when. Donors are no longer limited to creating their own private foundations (like the Ford or Gates Foundations) or giving directly to causes they support. A powerful but little-known philanthropic vehicle— the donor-advised fund, or DAF—is sweeping the charitable sector and bringing with it greater philanthropic opportunities for givers of more modest means. DAFs are a multi-billion-dollar force to be reckoned with in an industry that is evolving as rapidly as it grows—with enormous consequences that could shape modern philanthropy for decades. But as one conservative donor discovered, that change isn’t always good.

Changing How We Give

What are donor-advised funds? DAFs are a kind of “charitable savings account” managed by a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Like a donation to any tax-exempt nonprofit, donations to a DAF are tax-deductible to the extent permissible by law. Unlike traditional nonprofits, which may accept donations for general use or for specific projects, DAF providers (or “sponsoring organizations”) keep track of individual donor accounts. Donors can invest unlimited funds in their accounts, which are then invested to grow tax-free until the donor specifies which organizations should receive grants from that account. With account minimums as low as $5,000 and immediate tax advantages, it is little wonder that millions of savvy donors are moving their money into these funds.

Alternatively, some givers choose to put their money into their own private foundation, an independent organization that gives them complete investment and grantmaking control. But there are key reasons why a donor might put their money into a donor-advised fund instead. For one, the start-up cost of establishing a private foundation can be substantial—Vanguard Charitable Endowment Program (a commercial DAF provider) estimates the start-up cost of a new private foundation to exceed $15,000, plus ongoing operating and legal costs. Creating that foundation and registering it with the IRS can take weeks or months. In contrast, opening an account with a DAF provider is immediate, with no cost to donors beyond the investment management fees charged by the provider (usually 1 percent of the account balance).

Private foundations also have lower tax deduction limits than DAFs. According to the National Philanthropic Trust (NPT), a major DAF provider, DAFs can reap a tax deduction of 60 percent for cash gifts versus the 30 percent private foundations are allowed to deduct. Private foundations are only allowed to deduct 20 percent of adjusted gross income for stock or real estate gifts versus 30 percent for DAFs. Foundations are also subject to annual excise taxes (usually 1-2 percent of annual net investment income), from which DAFs are exempted altogether.

With this knowledge, it’s unsurprising that donor-advised funds are rapidly overtaking traditional grantmaking foundations as philanthropic heavyweights. According to NPT’s 2017 report, DAFs now spend out one-third as much as private foundations each year, but are only one-tenth their size by total account assets, with about $85.2 billion in DAF assets versus $865 billion in traditional foundation assets.

Private foundations also face stricter spend-out requirements than DAFs. The IRS requires private foundations to “annually distribute income for charitable purposes,” which means foundations must spend at least 5 percent of their net assets each year. In contrast, donors using a DAF can make annual donations to their accounts, reap immediate tax benefits, let the money grow tax-free, and ultimately direct their DAF provider to make grants to nonprofits of their choosing—without dealing with cumbersome IRS requirements.

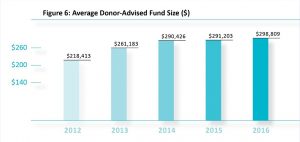

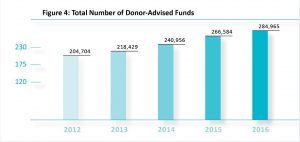

Unlike private foundations, which are often the domain of the ultra-wealthy, donor-advised funds are often more modest in size; the average size of a DAF account in FY 2016 was just under $299,000. According to a 2017 Foundation Source report, 58 percent of private foundations sampled have asset sizes over $1 million (however, the IRS reports that 66 percent of all U.S. foundations have asset sizes under $1 million). And there are many more of them: There were 284,965 DAFs in FY 2016 versus 83,276 private foundations.

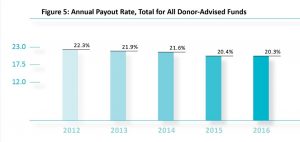

Since 2012, when NPT began its annual report, total contributions to DAFs have risen by nearly $10 billion to $23 billion. In fiscal year 2016 alone, contributions rose by 7.6 percent. That growth is setting new spending records every year, too. Grants made by DAFs have nearly doubled since 2012 to $15.8 billion, while the aggregate DAF payout rate for that period has exceeded 20 percent. In comparison, King McGlaughon, president of Foundation Source (a foundation advisor), has noted that private foundations averaged a payout of just 11.6 percent between 2008 and 2011.

Despite their recent growth in popularity, DAFs have been around for decades. They first originated in 1931 with the New York Community Trust following the initial creation of community foundations (grantmaking entities which serve geographically defined areas). DAFs were overhauled by the Internal Revenue Service in line with the 1969 Tax Reform Act, which established initial “distinctions between private foundations and public charities,” according to the Council on Foundations. The 1986 Tax Reform Act brought a new slew of nonprofit regulations, tightening reporting rules on taxable income.

The resulting upkeep in foundation management only encouraged the movement of money away from private foundations and into DAFs through the late 1980s and 1990s. As a result, new commercial DAF providers appeared—independent public charities created by major investment brokerage firms, including the Schwab Charitable Fund (Charles Schwab), Goldman Sachs Philanthropy Fund, Vanguard Charitable Endowment Program, and Fidelity Investments Charitable Gift Fund.

These four commercial DAF providers are some of the biggest charities in America. In July 2018, Schwab Charitable reported that grants from its DAF accounts between the first two quarters of the year were almost $2 billion, a 20 percent increase over the $1.6 billion donated the year before. Fidelity Charitable is even bigger: in 2017, the nonprofit made over one million donor-recommended grants totaling a staggering $4.5 billion. At the same time, Fidelity Charitable opened 21,000 new DAF accounts for some 30,000 donors.

In the next installment of Charitable Infidelity, learn how donors can use DAFs to protect their intent and anonymity.