Philanthropy

A Self-Protective “Deep State” in the Nonprofit Industrial Complex

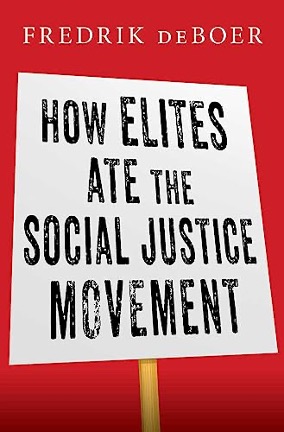

Activist, organizer, and journalist Fredrik deBoer argues in his new book that ideologically progressive nonprofits are, to their detriment, too institutionally conservative. So might be conservative ones.

License: Wikimedia Commons.

License: Wikimedia Commons.

“The idea of a deep state has become a culture-war football in recent years,” progressive activist, organizer, and journalist Fredrik deBoer writes in his new book How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement, “but there is no doubt that there is a layer of administrative employees with the government who do not change during transfers from one presidential administration to another and who influence the progress of American democracy.

“Washington has many, many permanent employees who are unelected and yet whose actions have serious consequences for our country,” he continues in a chapter of the book about “The Nonprofit Industrial Complex.” “That was the original concept of the ‘deep state.’” It reached mainstream recognition leading up to and during the administration of President Donald Trump, of course, who characterized it as an enemy of, well, a lot of things—including him, his actual or proposed policies, his populist supporters, and the country.

“Well—nonprofits are the deep state of American political activism,” according to deBoer. Supported by philanthropic elites, “[t]hey have influence beyond their numbers, they can direct the course of broad movements that should rightfully be led by volunteer organizers, and they pull those movements toward incrementalism and working within the system regardless of the radicalism of their employees.”

In How Elites At the Social Justice Movement overall, deBoer explores why recent idealistic progressive movements—Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and for economic justice among them—have failed and how they could succeed in the future. Risking oversimplification, he blames the failures on those elites deeply rooted in America’s upwardly mobile, educated class who fund, organize, and purport to speak for these movements. Albeit from deBoer’s decidedly left-of-center worldview, it is a populist book.

Criticisms, Categorized

In his harsh analysis of the nonprofit industrial complex and its failures, deBoer offers several specific criticisms. He categorizes them as: 1.) ones “that anyone might agree on, regardless of political leanings;” and, 2.) ones from those on left, like him, in particular.

His first, general, cross-ideological category includes: a.) a “lack of transparency and accountability;” b.) a question of whether they serve the needs of i.) those they purport to serve with their charity and programs, ii.) their donors, and/or iii.) their staffs; and, c.) an “elitism and lack of representation.”

DeBoer dwells more on his second category—what he labels “the left case against nonprofits.” “While it’s impossible to assign specific percentages to determine how left- or right-leaning the nonprofit sector is as a whole,” he notes, “[f]ew would question … that many of the best funded and most powerful nonprofits are ideologically progressive.” But “while most of these organizations may have progressive sympathies and progressive staffers, their effects in the world are often contrary to the lefts’ goals.”

His left case against nonprofits makes three claims. First, “[f]ar too many institutions are fixated on accumulating funds in a way that obscures their actual goals.” Yes, they do. This claim is actually just as easily made against nonprofits on the right too, though, and I think might thus be miscategorized if considered part of the left case, where he places it.

Second, “[b]y taking money that would eventually find its way into the tax system and putting it into the hands of an army of private organizations, the nonprofit industrial complex drains the public coffers and reduces public accountability.” This claim is properly categorized; it’s quite at home in—in fact, central to—a left case.

Precisely the Point

The third claim is one “that’s most relevant to the broader themes of this book,” as deBoer’s introduces it: “the role of nonprofits in left organizing.” Based on his “two decades of work in various organizing capacities, I can say that nonprofit organizations are both essential to the basic operations of left-wing activism and a drag on its ambitions and radicalism.”

In various contexts, he compares and contrasts the work of 1.) non-nonprofit, truly grassroots, “fly-by-night affairs”—where people just get together in someone’s living room or a union local after hours and planned how to try solving a problem—with that done by 2.) formally structured, usually much-larger, nonprofit groups—often led by professional staffs, including fundraisers.

“Organization and formal legal recognition are double-edged swords,” according to deBoer. “It’s true that nonprofits can be more reliable, more responsible, and better resourced than less ‘official’ groups. It’s also true that nonprofits can be overly cautious, mired in internal bureaucracy, structurally inclined toward centrism, and extraordinarily risk-averse.”

He cautions that

this line of criticism has nothing to do with the leftist bona fides of individuals who work for left-leaning nonprofits. Indeed, many of the nonprofit workers I’ve known have been very committed radicals. But this is precisely the point: nonprofits tend to be staffed by leftists and structurally conservative. They avoid risk because risk can undermine the continuing operations of the organizations. They resist change because implementing change can result in reprisals from authority within a given nonprofit. They avoid direct action and extralegal means because they have their special tax status to protect. The nonprofit sector’s conservatism isn’t about the people but about the nature of all institutions. It’s also about the power of inertia; as [Paul] Klein noted, “Many charities are mired in an old approach to social change that is also reflected in how they raise funds.” [Emphasis in original.]

These staffs constitute what deBoer then describes as the self-protective “deep state” safely housed in—in fact, protected by—the nonprofit industrial complex’s structure.

He underscores the “leftiness” of his concern. “The deficiencies of the nonprofit model are a particularly bad fit for radical-left organizing, as the left calls for big change, now,” he laments. “I’m sure a centrist nonprofit organization finds the bureaucracy and administrivia of such groups to be a cozy fit. For those people fighting for systemic change, for entirely different paradigms, the conservative tendencies of legally recognized nonprofits can be deadly.”

Recalling the very grassroots-energetic, well-funded, heady days of Summer 2020 for progressives allows deBoer to express his agita quite pointedly. “The street protests were messy, disorganized, and working toward vague goals; the nonprofits are conservative no matter their charter, obsess over fundraising, and focus first on perpetuating their own existence. It still not clear to me which is worse.”

Like deBoer’s first left-case claim about money trumping mission, though, I think this third claim about the double-edged swordness of nonprofits is actually again just as easily made against nonprofits on the right, too, and is thus also miscategorized if considered the most-important part of that left case. Fully realizing the book is about the left and that’s where deBoer’s experience lies, it’s a general claim, no?

Widening Application of the Claims

In acknowledging a governmental “deep state” and standing against a nonprofit “deep state,” deBoer is at least conceptually consistent with a stance, or perhaps merely an attitude or inclination, of Trump and those who saw in him a blunt, political rejection of both “deep states”—whether they’d have used or thought in those terms or not.

The Trump “movement,” if that’s what it was and appears to remain, was not anything close to a product of the then-existing, philanthropically supported conservative intellectual or activist/organizing nonprofit infrastructures. The right’s policy-oriented nonprofit industrial complex pretty much hated and resented him. It was scared and confused by him personally, along with those who cast their electoral lot with him politically. He and they flummoxed it. They still do.

Now, as deBoer recognizes, the left’s portion of the nonprofit industrial complex is very much larger, but the right’s smaller one could and probably should have to defend itself against almost all of his or similar claims, too—whether levied by him or, maybe better, others with standing among and within a right that’s been sometimes-contentiously refining or redefining itself in since 2016.

Influencing beyond numbers. Directing the course of others. Incrementalizing. Working within the system. Resisting change. Avoiding reprisals. Protecting tax status. Miring itself in the inertia of old approaches, reflected in how they raise funds from the out of touch. Defensive. Protective. Resentful of, sometimes condescending to, “new kids on the block.”

Almost all of the establishment philanthropy undergirding the nonprofit industrial complex was caught embarrassingly flat-footedby that which gave rise to the, and then the actual electoral, populist “primal-scream” rejection of elites—including philanthropic and philanthropically supported ones—in 2016. This included policy-oriented conservative philanthropy and that component of the larger nonprofit industrial complex it of which it is such an important, funding part. Those in it might perhaps benefit from a good close read of deBoer’s How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement.

This article originally appeared in the Giving Review on September 18, 2023.