Philanthropy

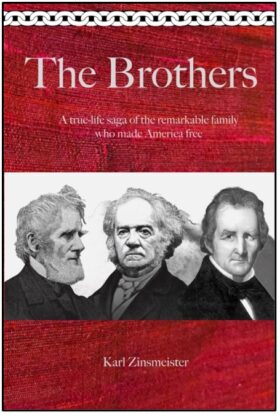

A Conversation With The Brothers Author Karl Zinsmeister (Part 1 of 2)

The former White House official and Philanthropy Roundtable vice president talks to Michael E. Hartmann and Daniel P. Schmidt about his new novel on the underappreciated history of the Tappan brothers and the ways in which they changed American culture, including through their philanthropy.

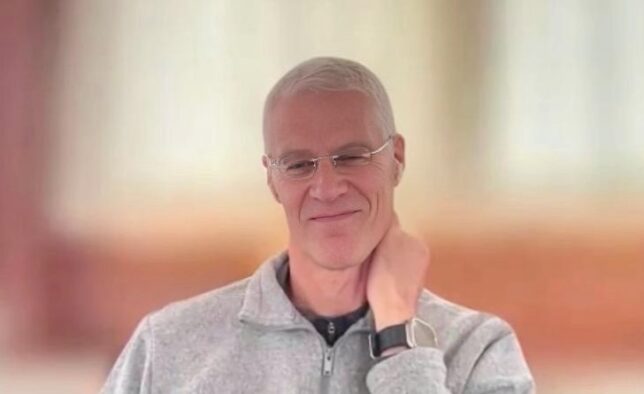

Karl Zinsmeister

Karl Zinsmeister

Karl Zinsmeister‘s length and variation of professional experience, along with his depth and breadth of knowledge, give rise to a wisdom from which more should benefit. Luckily, he shares it with humility and, relatedly, good humor.

Among other things, Zinsmeister directed the White House Domestic Policy Council during the administration of President George W. Bush, and was an aide to U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan. He has also been a vice president of the Philanthropy Roundtable and occupied the J. B. Fuqua Chair at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), for which he edited The American Enterprise magazine.

Zinsmeister created The Almanac of American Philanthropy—the authoritative, 1,342-page reference document on private giving in America—and has produced hundreds of other books, publications, podcasts, and films.

His compelling new historical novel The Brothers tells the underappreciated history of Arthur, Lewis, and Benjamin Tappan—fascinating, real-life siblings who transformed the abolition of slavery from a fringe campaign into a mass popular movement in America, including through their philanthropy, which also changed other things in the U.S. very much for the better.

Zinsmeister was kind enough to join us for a conversation late last month to discuss The Brothers. The almost 17-and-a-half-minute video below is the first part of our discussion; the second will is here. In the first part, we talk about why the Tappans aren’t featured prominently in history books, the love they had for each other even though they had serious disagreements, and the beliefs on which their philanthropy was based.

While working on The Almanac of American Philanthropy, “I discovered these two brothers, Arthur and Lewis Tappan,” Zinsmeister tells us. “I was thinking, why don’t I know about these guys? Because very quickly, I can conclude they were maybe the most-important transformers of culture in our country.” They “really turned the abolition of slavery from what, when they started, was a really kind of a fringy, not very well thought of movement into a mass popular crusade.”

“It was really their work that did that, but they also do this incredible other stuff through philanthropy. They were huge builders of schools and colleges,” he continues. “They were very instrumental in knocking down substance abuse, which is really out of control in Jacksonian America, three or four times our current levels of alcohol use. … They eliminated a lot of poverty. They did all kinds of wonderful” work against sex trafficking, which was also a huge problem in the America of their time.

“I started thinking about, why have they not shown up in our history books?” Zinsmeister says. “Well, there’s some good reasons for that. First of all, they were Puritans,” and they

became extremely successful Wall Street merchants, so they were rich business guys. … You got this kind of problematic background in modern terms. They were dead white European males with religious fervor and Wall Street connections. Who wants to make them Heroes right? Well, I’m sorry, but these guys were who they were and we really need to understand them.

Then Zinsmeister came to learn more about Arthur’s and Lewis’ older brother Benjamin—“the most brilliant of the group,” according to Zinsmeister. “I mean, everything he touched turned to gold.” Benjamin

was just an amazing mind, even maybe more talented than his amazing brothers, but he also had a completely opposite disposition. They were religious, humanitarian, good citizens who wanted to help the society around them. They were moderate in politics. He was a crazy, radical, Jacksonian Democrat. He couldn’t stand people. He was an incredible curmudgeon. He ran off to the frontier.

Benjamin became a U.S. Senator from Ohio. Arthur and Lewis on one end and Benjamin on the other “were on opposite sides of every public issue, and this was a time when that could be life and death,” Zinsmeister says. Arthur’s and Lewis’ “lives were threatened many times by the allies of their brother Benjamin, but somehow these guys managed to keep loving each other. They wrote these heartfelt letters that I’ve read in the Library of Congress.

“There’s a lesson in this for contemporary Americans,” Zinsmeister notes. “Can we disagree without hating each other?”

Zinsmeister also offers lessons that can be drawn from the Tappans’ philanthropy. “The genius of the philanthropy that the two philanthropic brothers, Arthur and Lewis, took up,” Zinsmeister says, is its basis in a belief that “man is not defined by bread alone. They did not believe in just giving people things. They didn’t believe that was the main thing that was missing.”

Arthur and Lewis believed “the main thing that’s missing in unhappy lives is a compass, a sense of moral purpose, a sense of meaning and dignity. So that’s where they put their emphasis,” Zinsmeister continues. “A lot of what they did was really aimed at building character and competence in poor and struggling and unhappy people, rather than giving them stuff. It really was so radically different than so much of what we see today. The word ‘moral’ almost has this negative connotation today.”

Not for Arthur and Lewis. “They thought that that you if you weren’t pursuing moral ends when you’re trying to help people, you very soon either become a lord of the manor who thought too much of himself or you would condescend to other people, or you face other temptations,” according to Zinsmeister. “They really felt like this is something you do because your faith calls you to it you do it, as an equal with the other person. … You’re not better just because you’re the giver.”

In the conversation’s second part, Zinsmeister discusses the Tappans’ belief in the primary role of individual human beings to do what’s right and get things done, as well as how today’s alternative faith in the promise of technology is a serious challenge for any return to that primacy of people.

This article first appeared in the Giving Review on March 11, 2024.