Green Watch

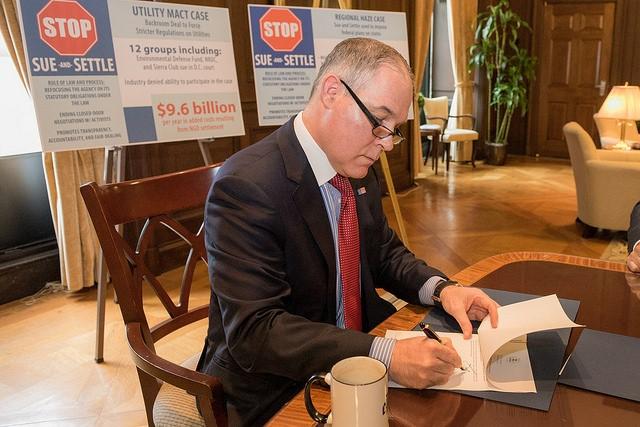

Scott Pruitt Ends the EPA’s “Sue and Settle” Legacy

Image via EPA.gov

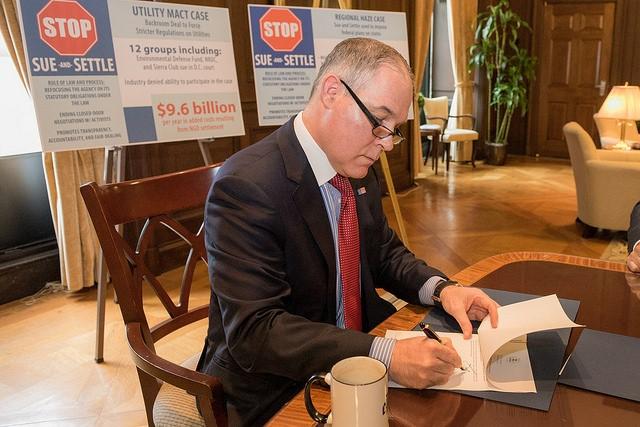

Image via EPA.gov

“The days of regulation through litigation are over,” says Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Scott Pruitt.

On October 16, Pruitt released a statement announcing that his agency is terminating the practice of accepting court-ordered consent decrees, a practice known as “sue and settle.” The statement also listed several changes the Agency will make to increase the its openness to the American people.

Pruitt—who, as Oklahoma’s Attorney General, sued the Obama administration EPA more than a dozen times for infringing on his state’s rights—says:

We will no longer go behind closed doors and use consent decrees and settlement agreements to resolve lawsuits filed against the Agency by special interest groups where doing so would circumvent the regulatory process set forth by Congress. Additionally, gone are the days of routinely paying tens of thousands of dollars in attorney’s fees to these groups with which we swiftly settle.

Pruitt’s new directive aims to increase transparency, “improve public engagement, and provide accountability to the American public when considering a settlement agreement or consent decree.”

The most important new rule excludes attorneys’ fees and litigation costs when the Agency reaches settlements. This will diminish the monetary incentive for leftist environmentalist groups to bring cases against the EPA because they will no longer be able to rely on taxpayers to cover their own court costs. By covering attorneys’ fees for these organizations, the EPA sent the message that litigation was an effective way to enact the environmental regulations that the groups wanted, without having to go through the process laid out in the Administrative Procedures Act (APA). According to the APA, agencies must propose new regulations to the Federal Register. The proposed regulations then go through a process of public consultation, including with the industry to be regulated, before going into effect as law.

To provide greater transparency and public engagement, the Agency will publish any complaints or petitions to review an environmental regulation, as well as intents to sue the Agency, within 15 days. If the Agency does agree to settlements or consent decrees, it will notify the public and the states and entities that any new rules or regulations will directly affect. Additionally, any modified consent decrees or settlements will allow for 30-day public comment before going into effect.

For years, especially under the Barack Obama administration, environmentalist special interest groups, like the Sierra Club, who support stricter regulations from the EPA brought suits against the Agency. These groups would accuse the EPA of not enforcing regulations on the books, often dealing with a statutory duty, or the enforcement timelines set by law. The Agency would settle with the groups, which almost always included covering the organizations’ court costs, in addition to hefty settlement sums. As part of the settlements, the organizations would also gain the additional regulations they wanted without having to go through the process laid out in the APA. In this way environmentalists managed to increase regulation without input from businesses who would feel the brunt of the regulations, or the taxpayers paying their court costs through the EPA.

In 2013, Chris Prandoni wrote in Green Watch:

Sue and settle allows lawyers for Big Green groups to walk into any EPA office and say, “We want this exact rule in place within 90 days,” and get a response something like, “Sure, pal. Anything else?”

Every major environmental law today—Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and so on—contains provisions for “citizen suits” that allow “citizen attorneys general” to sue alleged violators in federal court.

The problem is that Congress did not intend to empower Big Green attorneys routinely to chop off the citizen suit at the knees by removing the court trial.

But that is exactly what happens with sue and settle: Big Green activist group files suit against agency, agency negotiates chummy back-room settlement with the lawyers, then gets sham settlement rubber-stamped by federal court, bypassing a trial completely.

Prandoni cites one particularly egregious case, the “Regional Haze” requirement under the Clean Air Act which nationalized an issue that the EPA had traditionally left to the states because it is an aesthetic issue that doesn’t threaten people’s health. After a sue and settle agreement with environmentalists, the eventual costs that the EPA placed on the states, totaled billions of dollars more than the plans the states already had in place to deal with regional haze.

Another economically-damaging regulation imposed through the sue-and-settle process involved the Mercury Air Toxics Standards for Utilities. After a court struck down an attempt by the George W. Bush administration to impose a rule to reduce mercury from power plants, leftist environmentalist groups like the American Lung Association, the Environmental Defense Fund, and the Sierra Club sued the EPA over a missed deadline. The EPA settled with the groups and consented to write a new mercury rule. This came despite fine particulate matter (PM2.5) like soot, not air toxics like mercury, causing health problems such as asthma. Prandoni notes,

Most people may not know exactly what constitutes fine particulate matter, so the EPA and environmental activists simply misled the public, selling the rule as the “Mercury and Air Toxics” rule when it was really about particulate matter.

The National Economic Research Associates estimated that the new rules could cause the economy to lose roughly 1.65 million jobs by 2020 when added to other new EPA regulations on the electric power sector. Meanwhile, the EPA predicted the new rules would cost nearly $10 billion annually, while bringing Americans benefits worth no more than $6 million.

Writing while Obama’s EPA was riding high on the administration’s reelection, Prandoni urges opponents of EPA overreach to look to Congress for relief, predicting pessimistically that “reform will not come from within the bureaucracy.”

As we’ve heard before, elections have consequences—but they’re not always negative.