Special Report

Resettle with Caution: Hidden Costs to Social Programs

Resettle with Caution (complete series)

National Security Concerns | State and Local Obstacles | Hidden Costs to Social Programs

[Editor’s Note: This is the second part of an in-depth investigation into America’s refugee resettlement program. You can read the first part here.]

Summary: A vast network of foundations, non-profits, government entities and political organizations have a vested interest in the continued growth of the resettlement of refugees in America. Because they receive billions of dollars in federal grant money, publicly-financed, tax-exempt organizations have significant incentives to support political candidates and parties that will keep these programs alive. These organizations need to be thoroughly audited and the current network of public/private immigrant advocacy and resettlement organizations needs to be completely overhauled. Resettling refugees should be a voluntary, genuinely charitable activity, removing all the perverse incentives government funding creates.

Welfare and Other Costs

Refugee populations impose huge fiscal burdens on federal, state, and local governments beyond direct program costs. Costs include translation services, English as a second language classes in local schools, overburdened public housing, crime, and even terrorism.

When the 1980 Refugee Act was first passed, the federal government promised to cover 36 months of the states’ share of food stamps, Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF – the federal government’s primary cash assistance program), Refugee Cash Assistance (RCA), and Refugee Medical Assistance (RMA) provided to resettled refugees—a huge subsidy. Today it covers only 8 months of RCA and RMA, and no other state costs. Refugees rely heavily on local assistance, school budgets, costs for translation, and other services. These costs have exploded. Following is a sampling of problems in many U.S. communities:

- Amarillo, TX: 911 calls taken in 42 languages

- Amarillo, TX: English tutoring $1,300/student/month, while feds provide $100/student/year

- Buffalo, NY: 42 languages spoken in high school

- Lynn, MA: 49 languages spoken in schools, some in unknown dialects

- Lynn, MA: 200 percent increase in vaccinations, straining public health budgets; foreign student K-12 admissions doubled

- Manchester, NH: 82 languages spoken in high school, among lowest school ratings in NH

- Minneapolis, MN: An estimated 250 Muslims, many former refugees, have been recruited by ISIS. One quarter of these were Somalis from Minneapolis

- Minneapolis, MN: In 2015, 21 percent of Somalis were unemployed — three times the state average[1]

- Minnesota: more than one-half the Somali population is in poverty

- Nationwide: 20 to 49 percent of refugees test positive for latent tuberculosis (TB)

- Nebraska: 82 percent of active TB cases are among foreign-born

In 2016, the mayor of Amarillo, Texas, Paul Harpole, took his complaints to the state legislature. He told them, “We have 75 different spoken languages in our schools . . . Think you can take a child that’s never set foot in the school, he’s at fifth-grade level, he’s never seen the inside of the school, and get him to grade level in one or three years? It’s insanity.” Harpole said that based on per capita comparisons of other U.S. cities, Amarillo should take in between 65 and 90 refugees a year. Instead they are getting “about 500 a year.”

Amarillo’s experience points to the problem existent in many cities, where refugee contractors blithely ignore the problems they create by directing refugee populations into already overburdened communities. In New Hampshire, refugee bedbug infestations forced temporary closures at a library, a VA urgent care center, hotels, schools, and housing projects. The mayor of Manchester, which has taken in the most refugees in the state, repeatedly called for a pause in refugee resettlement. Dominic Sarno, the Democratic mayor of Springfield, Massachusetts, had the same request. Like every other politician who has complained about the problems refugees bring, regardless of political affiliation, he was vilified.

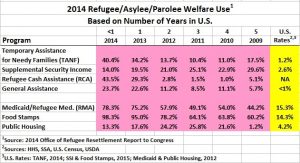

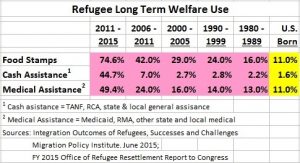

Refugees use welfare at very high rates for a long period of time. Table VI (below) details this use over the first five years for the 2009-2014 cohort as published by ORR’s annual report to Congress. Beyond five years, welfare use trails off slowly, but even after 40 years, refugee groups use welfare at rates higher than U.S. born citizens and even other immigrants.

The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) recently published what is probably the most detailed and complete estimate of refugee welfare costs yet produced. The tally includes estimates of:

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) formerly known as AFDC

- Medicaid

- Food Stamps

- Public Housing

- Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

- Social Security Disability Insurance

- Child Care and Development Fund

- Job Opportunities for Low Income Individuals (JOLI)

- Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)

- Postsecondary Education Loans and Grants

- Refugee Assistance Programs

- Earned Income Tax Credit and Additional Child Tax Credit

- State and local housing assistance

- English as a Second Language programs

- Special education programs

- Job training and employment search assistance

- Social services programs

- Other immigration assistance programs

FAIR estimated the total of these costs to be $15,900 per refugee for each of the first five years in the U.S. This included agency program costs which have already been largely documented. If the federal government program costs are removed, the per refugee net cost would be $7,632 after, including FAIR’s estimate of taxes paid by refugees. Over the most recent five-year period, an estimated 709,760 refugees have been resettled in the U.S, excluding unaccompanied alien children. The welfare cost for this group will be $5.4 billion over five years, or $1.1 billion per year.

Private Funding

Private foundations overwhelmingly support the refugee resettlement agenda. Much of that money is spent on advocacy groups like Welcoming America, but VOLAGs and affiliates receive substantial foundation funding in addition to taxpayer-funded government grants.

For example, HIAS has received at least $13.3 million from numerous, mostly Jewish foundations, since 1999. The Church World Service has received at least $106.4 million since 2000 from numerous foundations, including Open Society, Unbound Philanthropy, Ford, Schwab and others. Open Society’s 2017 Church World Service grant included $100,000 for affiliates in North Carolina and Ohio to “empower refugee and Muslim communities through trainings in leadership development, community organizing, Know Your Rights, de-escalation techniques, and civic participation.”

The International Rescue Committee has received over $325 million from private foundations since 1999, including Open Society ($2.3 million), Novo Foundation, ($58.7 million), Buffett ($31.4 million), Vanguard ($23.4 million), Tides ($8.0 million), Newman’s Own ($6.5 million), Unbound Philanthropy ($2.2 million), even Google ($2.8 million), and many others. $100,000 of Open Society’s money was slated “to provide support for the executive transition” at IRC. There is no further explanation of this grant, but this was the year Socialist former British MP, David Miliband took the helm at the International Rescue Committee. Miliband made $671,749 as CEO that year. Exactly what other transition was required beyond his exorbitant salary? A similar story could be told for the rest of the VOLAGs and their 300 plus affiliates.

Conclusion

This massive network of foundations, non-profits, government entities, and political organizations will continue to encourage investment in the refugee resettlement program, despite its deleterious effects on American society. Despite the calls for transparency, particularly in the previous administration, none of these organizations have been publicly audited. Given the millions of dollars that flow into this system, it’s long overdue for taxpayers to learn exactly how that money is spent

The Trump administration has taken many steps to rein in the resettlement program. It has instituted what it calls “extreme vetting,” which, in practice, is the kind of vetting that was supposed to be in place all along but hasn’t been, at least in recent years. The administration can only go so far with vetting, however. Many refugees come from failed political systems or countries already unwilling to cooperate with the U.S. Using databases and even identifying documents to evaluate the credibility of refugee claims is therefore difficult, and in some cases impossible. There will always be a risk when the program seeks to resettle thousands of people en masse every year.

The Trump administration also went to great lengths in its attempt to limit immigration from nations with terrorism concerns. The various so-called travel bans were met with overwhelming opposition from both leftwing activists and politically motivated jurists who obstructed the administration. This June, the Supreme Court affirmed in Trump v. Hawaii that the president has clear authority to impose such bans.

In the meantime, the least the government can do is assess the economic efficiency of the current resettlement program and consider the long-term effects of using politically motivated nonprofit organizations to administer billions of dollars of taxpayer funds.