Philanthropy

On the presidents of the Ford Foundation

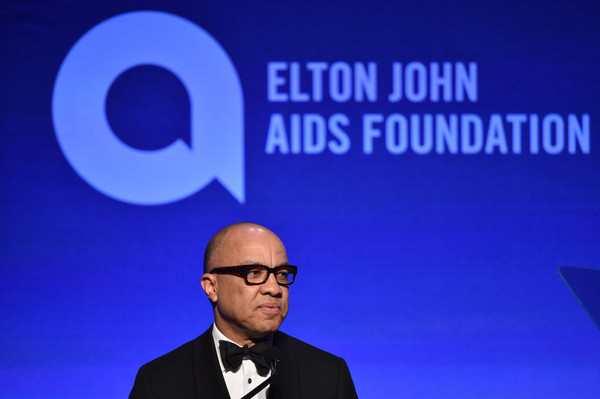

President of the Ford Foundation, Darren Walker, speaks at an Elton John AIDS Foundation event in November 2015.

President of the Ford Foundation, Darren Walker, speaks at an Elton John AIDS Foundation event in November 2015.

On the presidents of the Ford Foundation

By Martin Morse Wooster

Senior Fellow, Capital Research Center

(originally posted at Philanthropy Daily)

One of my useless achievements is that I think I can name all the presidents of the Ford Foundation without having to look them up. But even though I can name them, I can’t tell you what they were like. Part of this, of course, is that foundations tend to appoint people whose ascent up the greasy pole robs them of any personality. These foundation CEOs may be black or white, male or female, but they are uniformly pasty grey.

To my mind, the Ford Foundation has had traumas in its history that has caused its presidents to be bland and obscure. In the 1960s, when McGeorge Bundy was president, the foundation bestrode the narrow world like a colossus. But its relentless liberal activism resulted in a major Congressional investigation in 1969, and ever since then Ford has acted like a large foundation that wishes it was a small one.

After several decades of boring presidents, Ford has, in Darren Walker, nominated one who strives to be relentlessly interesting. He’s black! He’s gay! He has peculiar objects on his shelf! He’s gay! He wears classy ties! And wait: did I mention he’s gay?

Walker is profiled in the New Yorker by Larissa MacFarquhar. MacFarquhar is a very smart writer, and this piece has many good things in it.

One proof of her excellence is that she quotes Greater New Orleans Foundation president Albert Ruesga, who I remember from a talk at the Bradley Center in 2013 as being a fearless truth teller. He told the Chronicle of Philanthropy “the atmosphere of overweening politeness in American philanthropy is leading to our ruin. It keeps me from telling you, in the clearest possible terms, that your five-year, $2 million initiative to end homelessness is well-intentioned magical thinking at its best and boneheaded ignorance at worst.”

She also scores points by coming up with quotations from Henry Ford II about his disappointment with the Ford Foundation that were new to me. In 1973 the Ford Foundation conducted a series of oral histories for a history of the Ford Foundation that was never published.[1] Henry Ford II, who was, politically, an Eisenhower Republican, told interviewer Charles T. Morrissey that his 1948 decision to abandon family control of the Ford Foundation was “the biggest mistake I ever made” and a “horrendous error”:

“The Foundation’s been a fiasco from my point of view from day one,” Henry Ford II said. “And it got out of control and in the control of a lot of liberals…I’ve tried to break up the Foundation several times and have been unsuccessful…I didn’t have enough confidence in myself at that stage to push and scream and yell and tell them to f**k themselves, you know, which I should have done.” (Passage censored by me.)

Finally, there are two points in Darren Walker’s background that make him more interesting than most foundation CEOs. And no, it isn’t that he’s black or that he’s gay. It is that he has worked for a nonprofit and been a program officer at a major foundation.

Walker went to law school at the University of Texas, and after a brief career at a white-shoe firm, went to work trading securities for UBS. But after seeing the cover of a 1991 issue of The Economist with a cover line, “America’s Wasted Blacks,” he decided to become a poverty-fighter, and went to work for the Abyssinian Development Corporation, which tries to help poor people in Harlem.

“Raising money from foundations could be humiliating,” MacFarquhar writes. One program officer showed up 45 minutes late for a meeting, and didn’t apologize. Another program officer asked to see the neighborhood, and asked if he could bring his board to Harlem, Walker said that was a good idea, and said he would be happy to walk around the neighborhood and show the board around.

Walker was rebuffed. Walking was too much work! Couldn’t they take a bus?

“He had seen buses like that,” MacFarquhar wrote, “visitors from downtown staring out the window like they were on safari.”

In 2002 Walker went to the Rockefeller Foundation, where he headed the urban program. He found the Rockefeller offices “had a strange sense of calm. There was a slow deliberateness to the way things moved that he wasn’t used to—there was no sense of urgency.” At UBS, clients were constantly asking if trades were made. At Abyssinian, there was always a daily crisis.

But at Rockefeller all the grant applicants had no power. All they could do was sit and wait. Walker recalled one time where he noticed one of his subordinates had a million dollars in completed grant applications sitting on his desk. The subordinate was about to go on vacation. Shouldn’t he process the grants first? The subordinate said “it wasn’t a problem”—he could easily finish the paperwork when he returned from his holiday.

Walker learned from this episode “not to become an arrogant grant-maker who believed that people were deferential toward him and invited him to things and laughed at his jokes solely because of his own charm and intelligence.”

That’s a valuable lesson—and one most people in the foundation world don’t learn.

MacFarquhar spends a small amount of her profile on Ford’s current agenda. Walker has decided that all of Ford’s programs need to fight inequality. She describes some of the staff meetings she attended, it appears that Ford’s program officers are hard leftists whose reflexively uniform political views range from A to A- (B being too radical) and who would be appalled at Henry Ford’s support for limited government and self-reliance. The meetings, she writes, are ones where people have arguments but pretend they aren’t arguing, “a safe space with enough room for everyone’s concerns and problems.”

I’m sure that nearly all of what Ford does is bad grantmaking. But at least the foundation now has a CEO who has experienced the imbalance of power between grantmaker and grant recipient that makes the nonprofit world so frustrating. If Ford now respects their grantees, they deserve credit for that—even if their grants are wrongheaded.

[1] There still isn’t a history of the Ford Foundation.