Commentary

Juneteenth 2022

The Texas African American History Memorial in Austin, Texas. Credit: Moab Republic. License: Shutterstock.

The Texas African American History Memorial in Austin, Texas. Credit: Moab Republic. License: Shutterstock.

One year and one day ago, President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act (Pub. L. No. 117-17), making June 19 a federal holiday marking the day the last slaves in the former Confederate states were officially freed. (This year it’s observed on Monday, June 20, 2022.)

The liberation of the enslaved is certainly worthy of celebration, especially in the country that proclaims to the world “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It speaks to the very soul of the American Republic and its founding principles.

Why June 19—out of many possible days to celebrate the freeing of the slaves—was chosen is less obvious . . . and an interesting excursion through American history.

The Context

War by nature is chaotic and messy. So was ending the Civil War. While General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865—the date usually given as the end of the Civil War—President Andrew Johnson didn’t declare a formal end to the war until August 1866. Much happened in those 17 months.

Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, the second-largest Confederate army, surrendered shortly after Lee on April 26. Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, commander of about 10,000 Confederate soldiers in Alabama, surrendered his troops on May 4. A few days later, Nathan Bedford Forrest surrendered his cavalry corps at Gainesville, Alabama. Yet on May 12, a Confederate force defeated a Union force in the Battle of Palmito Ranch in Texas. Unaware that most of the Confederacy had surrendered, the CSS Shenandoah continued raiding Union shipping, including taking 10 whalers off Alaska on June 28. (The Shenandoah eventually surrendered to British authorities in Liverpool, England, on November 6.)

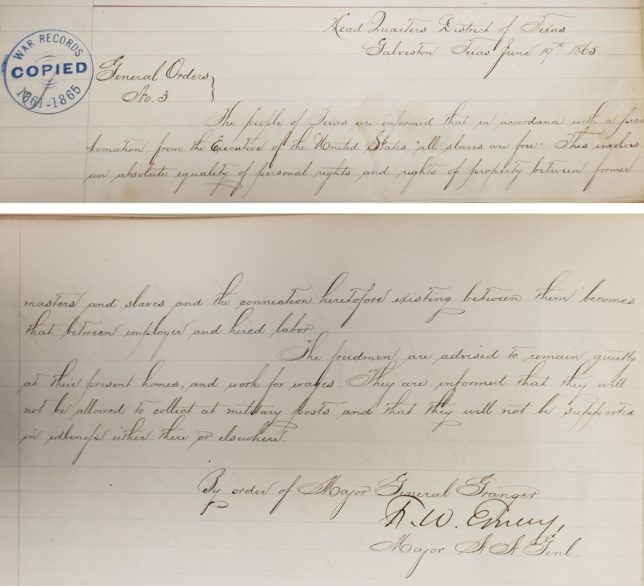

In the middle of this messy winddown, Union troops landed in Galveston, Texas, to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas, seemingly the last state in the former Confederacy where slavery persisted. The unit commander Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger accordingly issued General Order No. 3 on June 19, 1865:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

History of a Holiday

The freed slaves in Texas celebrated their new freedom, and in subsequent years celebrated their freedom on Juneteenth (a blend of “June Nineteenth”). As they moved from Texas to other states they took the joyful tradition with them, until “Today, many African Americans mark Juneteenth with parties, parades and gatherings with family and friends.”

The unofficial Juneteenth celebrations have continued and expanded through the years. It is also called “Juneteenth Independence Day,” “Freedom Day,” and “Emancipation Day.” In 1980, Texas made it an official state holiday. Florida, Oklahoma, and Minnesota recognized it in the 1990s. All other states recognized it as at least a day of observance by 2021. At present, it is an official state holiday in 24 states and the District of Columbia.

Yet it begs the question of why Congress didn’t make Juneteenth a federal holiday years ago. It certainly enjoyed broad support, especially among African Americans. In 2021, the Juneteenth bill passed the Senate with unanimous consent and 415-14 in the U.S. House of Representatives. Many credit the Black Lives Matter movement with pushing Juneteenth into the national spotlight, creating the political and social environment for it to become a federal holiday.

A Timeline of Emancipation

Some of the key dates in the emancipation of the slaves include:

1862

- September 22: President Abraham Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation.

1863

- January 1: The Emancipation Proclamation takes effect.

1865

- January 31: Congress passes the 13th Amendment, which would end slavery.

- April 9: General Robert E. Lee surrenders the Army of Northern Virginia.

- June 19: Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger issues General Order No. 3.

- December 6: The 13th Amendment is ratified, outlawing slavery in the United States and freeing slaves in the slave states that didn’t secede.

In the emancipation of the slaves, January 1, January 31, and December 6 are each arguably more significant that June 19, but the United States already significant federal holidays in December and January.

June 19 certainly makes at least as much sense as several other federal holidays, and it celebrates an arguably more significant event.