Special Report

Free Market Health Care Reform

Go Big On Liberty or Go Home!

Summary: Republicans’ health care overhaul is a huge disappointment so far. The House-approved bill repeals Obamacare taxes but leaves that system largely in place. But a glimmer of hope can be glimpsed in the House bill’s expansion of consumer choice.

To say that House Republicans “screwed the pooch” when they tried to repeal Obamacare in March this year is to put it mildly.

Without consulting the House Republican Conference, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-WI) released the text of the proposed “American Health Care Act” (AHCA), which he claimed would repeal Obamacare, lower the cost of coverage, and let consumers decide which health insurance best fits their needs.

But the only parts of the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. Obamacare) repealed are Obamacare’s taxes, the individual mandate, the premium subsidies, and a few regulations. The AHCA leaves in place Obamacare’s “protections” for preexisting conditions, the benefit mandates and the prohibition on annual and lifetime coverage limits. When challenged, Republicans who supported the AHCA defend it by saying that rules governing the budget “reconciliation” process would not allow them to repeal most of Obamacare.

The first part of this analysis examines why the AHCA would not have lowered costs or increased choice; debunks the nonsensical claim about the reconciliation process, and explains how the AHCA would only worsen one of Obamacare’s biggest problems—the notorious “death spiral.”

Clearly, conservatives and libertarians must push for a bill that greatly expands liberty in health care. The next part of this study examines how health care reform could achieve this goal by properly defining insurance; giving an additional option to the employer-base health insurance market; and allowing people more options with refundable tax credits and large HSAs.

Finally, this analysis proposes a solution to the politically difficult question of preexisting conditions. And it explains why refundable tax credits are not the “entitlement problem” that many conservatives and libertarians think they are.

The American Health Care Act (AHCA)

1. Insincerity

Speaker Ryan criticized Obamacare because it “was based on a one-size-fits-all approach that put bureaucrats in Washington in charge of your health care. The law led to higher costs, fewer choices, and less access to the care people need.” What Republicans proposed, he said, “will decrease premiums and expand and enhance health care options so Americans can find a plan that’s right for them. We also make sure Americans can save and spend their health care dollars the way they want and need—not the way Washington prescribes.” [1]

He added that the Republican plan “returns control of health care from Washington back to the states and restores the free market so Americans can access the quality, affordable health care options that are tailored to their needs.” [2]

Seeing that plan released in the future is something to look forward to. It would be a huge improvement over the AHCA which kept the Obamacare provision that requires all plans to cover ten “essential benefits.” This means that if a consumer wants to use the tax credits that the AHCA offers for the purchase of insurance, the insurance he or she buys must cover all of those benefits. Yet forcing insurers to cover benefits increases the cost of insurance. Were Ryan serious about lowering costs, he’d eliminate this provision and let the customers decide which benefits are “essential.”

Essential benefits must of course include maternity care. But what if our consumer is someone who has no immediate plans to start a family, and would like to forego the maternity benefit in favor of a lower premium? Here, Speaker Ryan decided that paying a higher premium to get an unwanted benefit best fit consumer needs.

Suppose a consumer would like to buy a policy that has an annual and/or a lifetime dollar limit since it would be cheaper than policies without those limits? Well, the GOP Leadership decided that such a plan would be inappropriate and kept the ban on annual and lifetime limits as specified in Obamacare.

The AHCA also maintained the Obamacare requirement that policies cover preventative services without cost-sharing. This provision is based on one of the biggest myths in health care: the ultimate canard that preventive services always save the health care system money. An exhaustive article in the New England Journal of Medicine dispelled that myth about a decade ago. NEJM researchers found that only 20 percent of preventive care saves money, while the remaining 80 percent actually increases health care costs. [3] Having a policy without preventive benefits or at least one that required cost-sharing would seem to be another way to lower the cost of health insurance. Apparently Washington thinks that such a cost-saving policy won’t fit consumer needs either.

The process set in motion when government forces consumers to purchase health insurance with specific benefits has already played out at the state level. Insurance regulation has become a pork barrel for interest groups that lobby on behalf of people with a particular disease and interest groups that lobby on behalf of physicians, nurses and others who treat those diseases. Such interest groups have been very successful over the last four decades in persuading state legislatures to mandate insurance coverage for the treatment for particular illnesses. Prior to 1970, state legislatures had only enacted a handful of such mandates; [4] by 2012, they had enacted over 2,200. [5] Each mandate adds between about one percent to upwards of ten percent to the cost of health insurance.

Fact: Unless Congress repeals Obamacare’s benefit mandates, Americans will be stuck with higher health insurance premiums.

2. Reconciliation Excuse

One argument that some Republicans used as to why the AHCA did not discard bigger chunks of Obamacare has to do with the legislative process itself: In the Senate, 60 votes are needed to end the debate on a piece of legislation before final approval can happen. However, a simple majority of only 51 votes are required on legislation dealing with either tax revenue or spending. This process is known as “budget reconciliation.”

Speaker Ryan claimed that budget reconciliation was the reason AHCA did not repeal Obamacare provisions such as the preexisting condition protections or the ten essential benefits. And indeed, that “reconciliation rules sharply restrict the provisions that Republicans might otherwise include when revamping the health care system.” [6]

According to this line of reasoning, the parts of Obamacare pertaining to preexisting conditions and insurance benefits are described as “regulations,” not revenue or spending matters. And as such, they do not fall under reconciliation process.

First: This attitude is nothing more than an elaborate excuse. Regulations can be passed or repealed under reconciliation as long as they are interconnected with revenue and spending matters in a bill, [7] –something that is very likely in the case of Obamacare. Indeed, it appeared that Speaker Ryan and other Republicans were acting on this interpretation of reconciliation since the AHCA would have repealed Obamacare regulations pertaining to age rating and actuarial value of insurance!

Second: Even if reconciliation prohibited repealing regulations, Republicans might have been creative about their use of the reconciliation process. For example, senators could add an amendment forbidding insurers from selling insurance that lacked the preexisting condition “protections” and the ten essential benefits unless they agreed to pay an annual tax of $1. Such a policy would have an immediate budgetary impact, and it would give insurers the freedom to sell and consumers the freedom to purchase a much wider array of insurance options.

Some have argued that using the reconciliation process in this “creative” manner would set a precedent Democrats might exploit the next time they come to power. [8] In other words, once Republicans stretch the reconciliation process, Democrats could use it to add more government to health care system—or even impose a single-payer system. The fatal flaw in this kind of quid-pro-quo is best demonstrated by the consideration that Democrats will use reconciliation in such a peremptory way regardless of what Republicans do in the current Congress. Democrats have already used the reconciliation process in novel ways to pass Obamacare. Anyone who thinks they won’t further push the envelope the next time they are in control of the national legislature has got another thing coming!

Speaker Ryan used the reconciliation process as an excuse to leave in place those parts of Obamacare that drive up the cost of insurance. There is no excuse for this kind of sloppy lawmaking.

3. Death Spiral on Hyper-Drive

Had it been enacted, the AHCA would have repealed the onerous individual mandate and the premium subsidies that are part of Obamacare. However, it did not repeal the prohibition against insurance companies denying coverage to people with preexisting conditions. Instead, it would have permitted insurers to impose a 30 percent surcharge on top of regular premiums on anyone who’s coverage has lapsed for at least 63 days, or who has not had coverage of any kind for that period or longer. An individual or family would only have to pay the surcharge in the first year of coverage after which they would pay the regular premiums.

The problem with the AHCA wasn’t that it forced insurers to take people with preexisting conditions as long as they paid a surcharge. Like Obamacare, it forced insurers to take people with preexisting conditions, period. Obamacare took what had been known as the “individual health insurance market” and forced it onto the heavily regulated Potemkin markets called “exchanges.” These exchanges are now collapsing, and when that collapse runs its course at best a few insurers will remain standing. The AHCA, however, threatened to eliminate the individual insurance market entirely.

Basic economics dictate that a stable “insurance pool” must have a sufficient number of young and healthy people to “cross-subsidize” the older and sicker. Unfortunately, Obamacare gives the young and healthy an incentive to forego insurance on the exchanges because: (1) exchange regulations cause the price of insurance to be higher for young and healthy people than what they would pay in a free market; and (2) even if a young person gets seriously ill, he or she can still buy a policy because Obamacare does not permit insurers to turn away people with preexisting conditions. When not enough young people, generally ages 18 to 34, sign up for insurance, the “insurance pool” is heavily comprised of people who are older and sicker. This causes insurance prices to rise so that insurers can cover their costs. As premiums go up, even more young and healthy people drop out, prices increase again, and the process repeats itself. Eventually, many insurers lose money, causing them to leave the market. This results in less competition which also causes premiums to rise. The term for this process is “death spiral.” (For a good history on this, see the late Conrad Meier’s “Destroying Insurance Markets.” [9])

Obamacare tried to combat the death spiral with his controversial individual mandate and with premium subsidies. The individual mandate required everyone, including the young and healthy, to purchase insurance or pay a fine. Subsidies applied to premiums helped people pay for insurance on the exchanges and were based on income status. The lower a person’s income, the bigger the subsidy he would get. Since younger people tend to have lower incomes, presumably this would encourage enough of them to sign up on the exchanges.

In this case, both carrot and stick, incentives and disincentives proved insufficient.

For the insurance pools on the exchanges to be stable, the Obama administration estimated that 38 percent of the sign-ups needed to be in the 18-to-34 age range. However, people in that age range never amounted to more than 28 percent of the people who participated in the exchanges. Recently Mark Bertolini, CEO of insurance giant Aetna, said that the exchanges are in a “death spiral” and for good reason. Going into 2017, the average premium for policies on the exchanges increased a hefty 25 percent. Many of the major insurers—Aetna, BlueCross BlueShield, Humana, UnitedHealth—have either left most of the exchanges or are planning to next year. From 2016 to 2017, the number of people eligible for the exchanges who had access to only one insurer jumped from two percent to 17 percent.

The simple truth is that for health insurance markets to function properly, insurers must either be able to deny coverage to those with preexisting coverage or take preexisting conditions into account when underwriting premiums.

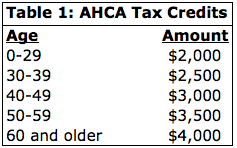

However, had the AHCA prevailed, it would have kicked the downward spiral to terminal velocity. First, in the year 2020 it would have replaced the premium subsidies with refundable tax credits based on age, with $2,000 for those up to age 29 and $2,500 for those ages 30 to 39. (For a full breakdown of the tax credits, see Table 1). Right now, that’s probably more than most people ages 18 to 34 on exchanges receive in premium subsidies. But premium subsidies are based, in part, on the cost of premiums. If premiums keep rising by an average of 25 percent annually between now and 2020, it’s possible that the AHCA’s tax credits will be less than the premium subsidies. For now, though, let’s call it a wash.

Much worse, the AHCA would have replaced Obamacare’s attempt to provide short-term incentive to purchase an insurance policy with a long-term incentive not to buy one. Notoriously, if a consumer doesn’t purchase insurance under Obamacare, the Internal Revenue Service deducts a penalty from any tax rebate he or she might receive. The AHCA would replace that penalty with a 30 percent surcharge that insurers can charge anyone who has allowed their coverage to lapse for more than 63 days.

In retrospect, it appears that younger people didn’t care much about the individual mandate. Thus, if younger people don’t care about a tax penalty that occurs annually, why would they care about a 30 percent surcharge that they likely won’t face for decades? About 80 percent of health care expenses occur after the age of 40, so most 18-to-34 year olds can put off worrying about that surcharge for quite some time.

Indeed, thanks to Speaker Paul Ryan and other congressional Republicans, it would be much easier to determine the optimal time to purchase health coverage. Here’s an example: A consumer in his late 50s has knee problems that are going to require a joint replacement. Let’s say that a policy on the individual market would normally cost this consumer about $10,000 annually. But, since he hasn’t had insurance in a while, the insurance company will add a surcharge, costing him $13,000 annually. If the knee replacement costs about $15,000, then he gets a pretty good deal. And if he has a much more expensive illness–kidney failure, heart disease, cancer–then that surcharge is a bargain.

Finally, would insurers even deign to offer coverage in the individual market under these conditions? They are already dropping out of a market where the federal government is trying, albeit feebly, to provide incentives for people to purchase insurance before they get sick. Under the AHCA, people would have big incentives to avoid coverage until they are very sick. It’s hard to see how insurers make any money in that kind of market.

For insurance markets to work, people need to purchase insurance before they develop a serious illness, and the only way to make that work is to allow insurers to deny coverage to those with preexisting conditions. Certainly, any bill that replaces Obamacare will need to provide assistance to people with preexisting conditions, especially those who have bought insurance on the exchanges.

That said, before the unveiling of the AHCA it had been difficult to see how the individual insurance market could be made any worse than it is under Obamacare. Unfortunately, Speaker Ryan came close to doing just that.

Greater Health Care Freedom

1. Defining Insurance

The AHCA offered tax credits for the purchase of health insurance. The tax credit is refundable, meaning that an individual can claim even if he has no income tax liability. The amount a person receives increases with age, as displayed in Table 1.

Table 1

A family could receive tax credits for its five oldest member up to $14,000.

If the AHCA or any other health care legislation is going to offer tax credits for the purchase of health insurance, then that legislation must first define health insurance. Obviously, we don’t want people using their tax credit to buy things that are not health insurance or health care related. Nor do we want insurance to be defined the way both Obamacare and the AHCA define it– as a set of mandated benefits.

That said, it’s possible to define health insurance in a manner that gives individuals and families greater freedom in deciding what kind of health insurance they want to buy. Health care reform legislation should define health insurance in the following way: The sole requirement for using the tax credit to buy health insurance must stipulate that the purchased insurance provide at least a minimal level of coverage. Legislation could ensure that an individual or family would qualify for a tax credit as long as the insurance they purchased covered at least, say, $100,000 worth of medical expenses annually.

Of course, this figure isn’t set in stone. Congress might set the limit at $250,000 or more, anything to ease its passage into law. The point is that defining the tax credit according to certain minimal coverage limits would make insurance very affordable; it would also be the only restriction on the tax credit. So if a consumer only wants to purchase insurance that covers one of the ten essential benefits, he or she is free to do so. Also, if a consumer wants to purchase a policy that provides more than $250,000 coverage, he or she is free to do so. If a family wants a policy that covers benefits other than the ten essential ones, they would be free to buy one.

Finally, the definition of health insurance should be expanded so that people can buy “continuity policies.” A continuity policy was an innovation introduced by UnitedHealth in 2008. The passage of Obamacare rendered such policies obsolete. A consumer who purchases a continuity policy is literally buying the “right to buy an individual health policy at some point in the future even if you become sick.” [10] In the case of UnitedHealth, a consumer would “pay 20 percent each month of the current premium on an individual policy to reserve the right to be insured under the plan at some point in the future.” [11] Continuity policies could be relevant again in a post-Obamacare health care system; individuals and families should be able to use tax credits to buy them.

2. More Freedom for Health Savings Accounts

The AHCA would have expanded Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). Under the AHCA, an individual could put up to $6,550 and a family $13,100 annually tax free in an HSA if they have a qualified high-deductible plan; people age 55 and older can make a catch-up contribution of $1,000; people can withdraw money from their HSAs tax free to pay for qualified medical expenses, including over-the-counter medications; and the tax penalty for withdrawals for non-medical expenses is reduced from 20 percent to 10 percent. [12] However, this reduction should be greater.

Republicans ought to pursue “large HSAs” in future legislation. Large HSAs would permit individuals and families to put much greater amounts into an HSA tax free. As one example, the Cato Institute’s Michael Cannon has suggested that individuals be allowed to deposit $8,000, and families $16,000 tax-free in a large HSA. [13] Instead of the requirement under current law that an HSA must be coupled with a high-deductible health plan, people would be able to use the money in their large HSAs to pay for the premiums of any type of health insurance they wanted.

Large HSAs should also be used to change the employer-based health insurance system. Under the current tax system, employees get an unlimited tax exemption for health insurance if they purchase it through their employer. As such, employees have a big incentive to purchase too much health insurance since every extra dollar of income is taxed at the marginal rate while every dollar of health insurance is tax-free. This often causes health insurance prices to grow at a rate much higher than inflation. [14] Unfortunately, the AHCA does not change the employer-based health insurance system.

Health care reform must allow employers to switch from the current tax system to one of large HSAs. Giving employers the option of switching over to a system of large HSAs would enable them to get out of the health insurance business; it would also empower their employees to purchase health insurance that best fits their needs. In this way, insurance would be made much more portable: An employee could keep his insurance regardless of whether he found a new employer. The large HSAs would be portable as well. The employee would keep whatever an employer put into the large HSA. The employee could also ask his new employee to fund his large HSA. Under health care reform, the employer should have this option even if all of his other employees are still insured under the current employer-based system.

Large HSAs provide employers with many advantages over the current system. First, it allows employers to rid themselves of having to shop for health insurance whenever premiums increase too much. With large HSAs employers would know from year to year roughly how much they would be spending on their employees’ health benefits. Finally, in recent years, employers have moved away from “defined benefit” pensions toward “defined contribution” pensions. [15] Given these advantages, it is likely that most employers would, over time, drop the current employer-based health insurance system and adopt large HSAs instead.

Indeed, giving employers the options of large HSAs would go a long way to solving the inefficiencies of the current system. Employees would no longer have an incentive to put every extra dollar of compensation into health insurance since the large HSAs would limit how much of their compensation could be tax free for health insurance purposes. With a fixed amount of dollars available for health insurance, employees would be more careful when purchasing health insurance and when consuming health care resources. This, in turn, will drive down health care costs.

3. Savings Instead of Insurance

Under the original version of the AHCA, an individual or family purchasing insurance that cost less than the tax credit would be able to deposit the savings in an HSA. As it became clear that the AHCA was not going to pass the House of Representatives, the GOP leadership removed the provision. [16] The money would instead be diverted to increasing tax credits for lower-income elderly people, something that appealed Republican moderates in the House.

This change was myopic. Letting consumers save any excess tax credit incentivizes them to shop around for the best deal. By making that change, Republicans all but eliminated the AHCA’s ability to lower health insurance costs. For example, consider a 28-year-old man who wants to purchase a policy for $100 per month that has a $1,000 annual deductible. Prior to the change, he would have incentive to shop around for such a policy; he would be able to use $1,200 of the tax credit to pay for the premiums and then put the remaining $800 in an HSA to help pay for the deductible. But with the change, he can no longer put the remaining $800 in an HSA—and so has far more incentive to purchase an insurance policy that costs as close to $2,000 annually.

Health care reform should also permit individual and families to save the tax credits or the money in their large HSAs without using them to purchase insurance. For some people at certain times in their lives, saving money for future health care expenses may make more sense than buying insurance. All should have the liberty to make that choice.

Allowing tax credits and large HSAs makes practical sense, especially for those living in states with over-regulated health insurance markets. In such states health insurance is exorbitantly expensive. Try being a 31-year-old single female living near Albany, New York on a moderate income: The AHCA offers people ages 30 to 39 a $2,500 refundable tax credit. This would cover only 60 percent of the cost of an insurance policy for a 30-something living in Albany.

Letting people save money in their large HSAs or save their tax credits without purchasing insurance serves two purposes in states that are over-regulated. First, it enables people who find health insurance to be too expensive another means of paying for health care. While the amounts that can be saved with HSAs or tax credits will not pay for catastrophic health care costs, they will often be enough to pay for small or intermediate costs. Second, people saving money in their HSAs or saving their tax credits instead of buying insurance, is an indicator that a state’s health insurance market is over-regulated. As the number of people doing this grows, it will be harder and harder for state politicians to ignore the trend; consequently they will feel pressure to deregulate their markets. And if politicians put on their blinders, insurance companies will certainly notice it. Desiring the business of the uninsured, insurance companies will lobby state politicians for deregulation.

Preexisting Conditions

A high-risk pool is a defined as a government-funded program that insures people who, because of a preexisting condition, cannot obtain insurance on the private market. The State Innovation Grants and Stability Program, one of the better provisions of the AHCA would have provided grants to state governments for the purpose of setting up high-risk pools and helped them find other ways to help people with preexisting conditions. The states are the laboratories of democracy. If a viable solution exists to the problem of preexisting conditions, then letting states experiment is the best way to find it.

However, in the murky period between the repealing of Obamacare and the first state-sponsored high-risk pool, many people on the exchanges are at risk of losing their insurance. Republicans can fix this. If they do, they will put Democrats on the spot.

Republicans would be wise to include a federal high-risk pool in their health care reform proposal for people who currently obtain coverage through the exchanges. This high-risk pool would give every individual and family a benefits package exactly like the one that they have under their current insurer on the exchange. So, for example, if a man living in Maryland had a CareFirst BlueChoice HMO HSA Bronze plan through the Maryland exchange, he would receive a set of benefits on the federal high-risk pool exactly like the one he has with CareFirst. People would pay the same premium to the high-risk pool they currently pay on the exchanges.

Private insurers should be paid a fee to manage the benefits of the people in the high-risk pool. Thus, the man who had a CareFirst policy in Maryland would have CareFirst manage his benefits. The federal government and the premiums he paid would fund his care; his expenses would no longer be the liability of CareFirst. But by letting CareFirst manage his benefits, he would, in effect, have the same insurance policy on the high-risk pool that he had on the exchange.

This would help people who lose exchange coverage because of the repeal of Obamacare as well as people who lose exchange coverage because of the death spiral. For example, health insurer Humana announced in February that it would be leaving the exchanges in early 2018. Humana currently covers 150,000 people on the exchanges. If these people opted to move to a federal high-risk pool, and Humana opted to manage their benefits, then they would effectively keep their insurance.

A federal high-risk pool would blunt criticism levelled at Republicans that an Obamacare repeal would leave many millions without insurance. The GOP could then go on the attack. Republicans could point to the federal high-risk pool as a solution for the people who are losing coverage because Humana and other insurers are leaving the exchanges. They could then pressure Democrats to support the high-risk pool proposal: “Do you want our citizens on the exchanges to lose their insurance?” Republicans might ask. How would the Democrats answer?

Tax Credits: An Entitlement Problem?

Some conservatives and libertarians view using refundable tax credits for the purchase of insurance as an “entitlement”– that is, a financial benefit provided by taxpayers to which a recipient is legally entitled as long as he or she meets the eligibility requirements. One of the most prominent purveyors of this argument is Michael Cannon of the libertarian Cato Institute. He argues that, like other entitlements, politicians will expand tax credits over time:

…like Obamacare, the…tax credits [in Republican health care plans] are “refundable.” So if you have no income-tax liability, or if it’s just less than the amount of the credit, you get a check from the government…Obamacare’s “tax credits” are roughly 80 percent government spending. With a Republican imprimatur on such spending, Obamacare supporters could probably increase spending more than they could under Obamacare itself. [17]

Undoubtedly politicians like to increase spending as a way to win votes. Over the decades, Congress has expanded entitlements such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid to please a variety of constituents. So, in theory at least, politicians would do the same with tax credits for health insurance.

But does this theory hold water? To test it, look at the five tax credits that people most often claim on their tax returns: They are the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit, the retirement saving contribution credit, the education tax credit, and the foreign tax credit. [18] The education tax credit is actually two different credits, the American opportunity and the lifetime learning credit (he Internal Revenue Service data lumps them together as “education credit”). For an explanation of each of these tax credits, see the Appendix below.

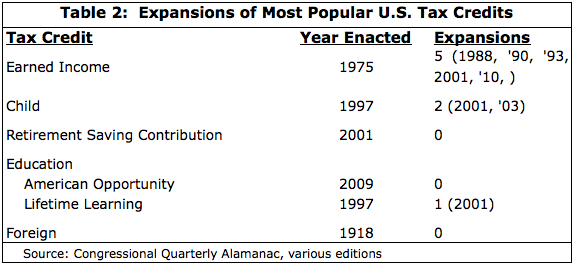

Table 2

As Table 2 shows, politicians do not often expand tax credits. The earned income tax credit has been expanded five times, about once every eight years since it was enacted, more than any other credit. The earned income tax credit appears to be the exception: None of the other tax credits have been expanded more than twice, and three have never been expanded at all. The earned-income tax credit has probably been expanded for two reasons that do not apply to the tax credits in the AHCA. First, the earned-income tax credit was not indexed for inflation in roughly the first decade of its existence, something that increased pressure to expand it. Once it was indexed for inflation, pressure continued to increase it because wages often grow faster than inflation, thus further reducing its value for recipients. By contrast, the AHCA tax credit is indexed for inflation and will be used to purchase insurance, not boost incomes.

While it is possible that the tax credit in the AHCA will prove too tempting to member of Congress, evidence suggests that it will not be a prime candidate for expansion in the years to come.

Conclusion

On May 4, 2017, the House of Representatives passed a substantially modified version of the AHCA, 217 to 213. The new version would let states opt out of most Obamacare mandates. It would keep the preexisting condition “protections,” but states would have the option of allowing insurers to underwrite premiums based on a person’s health status. In such states health insurance markets would function properly.

Additionally, a consumer who buys an insurance policy that costs less than the amount of the tax credit would get to deposit the difference in an HSA.

The new AHCA does not define insurance as a dollar amount of coverage. It cannot do so as it keeps the Obamacare prohibition on annual and lifetime limits. However, it does leave the definition of insurance up to state governments. Thus, states can experiment with different definitions of what constitutes insurance. Over time policymakers will gather evidence of what types of definitions work best.

Unfortunately, the new AHCA leaves the employer-based tax exclusion in place. And it doesn’t give people the options of saving their tax credits instead of buying insurance. Still, it represents a substantial improvement over the original AHCA, one that will allow states with failing Obamacare exchanges to experiment with free markets.

The new AHCA is a big step–but only a step–in the right direction. Improvements to the health care system lacking in the bill are policies we can reintroduce at a later time. But for now, conservatives and libertarians should support the bill and work to ensure that the Senate does not water it down.

Appendix

Earned Income Tax Credit: A refundable tax credit for low- to moderate-income working individuals and couples, particularly those with children. The amount of EITC benefit depends on a recipient’s income and number of children.

Child Tax Credit: A refundable; provides a credit of up to $1,000 per child under age 17.

Retirement Saving Contribution Credit: A non-refundable tax credit worth up to $1,000 for an individual and $2,000 for couples filing their taxes jointly that is available to lower income individuals and households that contribute to qualified retirement savings plans, such as a 401(k).

American Opportunity Tax Credit: A credit for qualified education expenses paid for an eligible student for the first four years of higher education. The maxim available is $2,500 annually per eligible student.

Lifetime Learning Tax Credit: A credit that is equal to 20% of the first $10,000 of qualified tuition and related expenses paid by the taxpayer.

Foreign Tax Credit: A non-refundable tax credit for income taxes paid to a foreign government as a result of foreign income tax withholdings.

[1] Our Time Is Now, “Frequently Asked Questions,” at https://housegop.leadpages.co/healthcare/ (April 11, 2017).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Joshua T. Cohen, Peter J. Neumann and Milton C. Weinstein, “Does Preventive Care Save Money? Health Economics and the Presidential Candidates,” New England Journal of Medicine, Feb. 14, 2008.

[4] Victoria Craig Bunce and J.P. Weiske, “Health Insurance Mandates in the States 2010,” Council for Affordable Health Insurance, 2010.

[5] http://docplayer.net/1257292-Health-insurance-mandates-in-the-states-2012.html

[6] Brandon Morse, “Paul Ryan: GOP health-care bill is ‘closest we will ever get’ to repealing Obamacare,” The Blaze, March 10, 2017, at http://www.theblaze.com/news/2017/03/10/paul-ryan-gop-health-care-bill-is-closest-we-will-ever-get-to-repealing-obamacare/ (March 14, 2017).

[7] Daniel Horowitz, “A Destroyed Health Care System Because of a… Parliamentarian?” Conservative Review, Jan. 10, 2017, at https://www.conservativereview.com/commentary/2017/01/a-destroyed-health-care-system-because-of-a-parliamentarian (March 14, 2017); and Daniel Horowitz, “Lie, Lie, Lie: Ryan and Co. Caught in Twisted Pretzel of Lies To Preserve Obamacare,” March 10, 2017, at https://www.conservativereview.com/commentary/2017/03/lie-lie-lie-ryan-and-co-caught-in-twisted-pretzel-of-lies-to-preserve-obamacare (March 14, 2017).

[8] “Your Mommacare,” Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Friends, March 9, 2017, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OHV7Dpwt44k (March 16, 2017).

[9] Conrad F. Meier, Destroying Insurance Markets, The Heartland Institute, March 1, 2005.

[10] Reed Abelson, “UnitedHealth to Insure the Right to Insurance,” New York Times, Dec. 2, 2008, at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/03/business/03insure.html (March 17, 2017).

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Summary of the American Health Care Act,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2017, at http://files.kff.org/attachment/Proposals-to-Replace-the-Affordable-Care-Act-Summary-of-the-American-Health-Care-Act (March 8, 2017).

[13] Michael F. Cannon, “Large Health Savings Accounts: A Step toward Tax Neutrality for Health Care,” Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 2008, Vol. 11, No. 2, at http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/articles/cannon-large-health-savings-accounts.pdf (March 10, 2015).

[14] For a summary of the literature on the impact of the employer-based tax exclusion, see Jonathan Gruber, “Tax Policy for Health Insurance,” in Poterba, James M. (ed.), “Tax Policy and the Economy”, 2005, 19, 39-63. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

[15] David Hogberg, “Refundable Tax Credits or Large Health Savings Accounts? Let’s Do Both,” National Center for Public Policy Research, National Policy Analysis No. 676, October 2015.

[16] Speaker Ryan Press Office, “Speaker Ryan Statement on Improvements to the American Health Care Act,” March 20, 2017, at http://www.speaker.gov/press-release/speaker-ryan-statement-improvements-american-health-care-act (March 22, 2017).

[17] Michael F. Cannon, “On health care, Walker and Rubio offer Obamacare lite,” New Hampshire Union Leader, Aug. 15, 2015, at http://www.unionleader.com/article/20150828/OPINION02/150829238/1009/NEWS12&template=mobileart (March 12, 2017).

[18] “SOI Tax Stats – Individual Income Tax Returns,” Internal Revenue Service, Table 1—Individual Income Tax Returns: Selected Income and Tax Items, 2015, at https://www.irs.gov/uac/soi-tax-stats-individual-income-tax-returns (March 10, 2017).