Book Profile

Waging a Good War: Tortured Thesis

Waging a Good War: A Mostly Unhelpful History of the Civil Rights Movement (full series)

Tortured Thesis | He Is Writing This Because . . .

The Army of One

Tortured Thesis

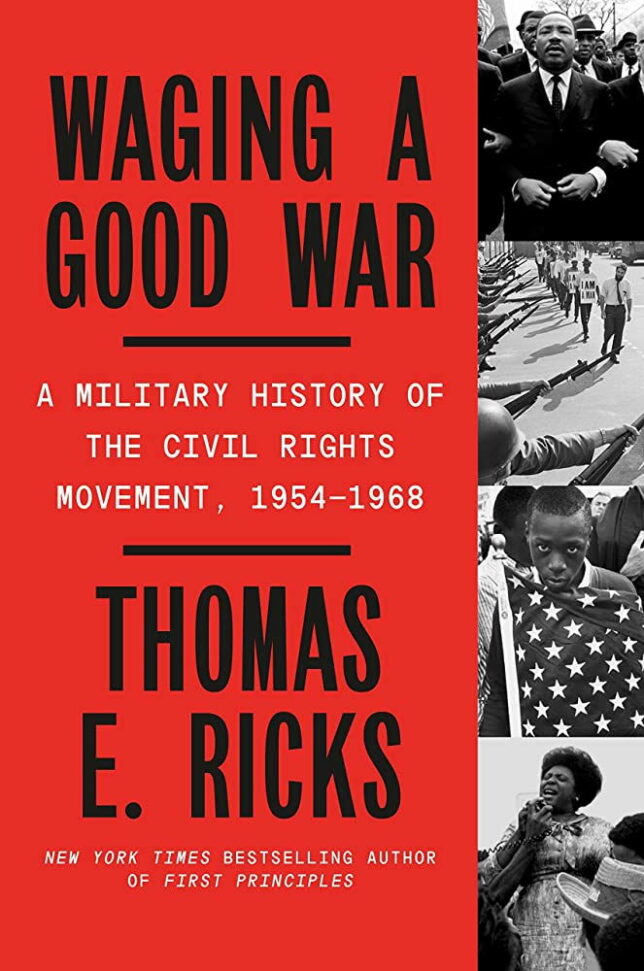

“A search of the American Historical Association’s database of doctoral dissertations in recent decades found more than 250 that studied the American civil rights movement,” wrote journalist Thomas E. Ricks, in the preface to his book Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954–1968. The book exists, according to its author, because of his “surprise” that he couldn’t find just one aspiring historian who “looked at the Movement through the prism of its similarity to military operations.”

Waging a Good War: A Military History of the Civil Rights Movement, 1954–1968 exists, according to its author, because of his “surprise” that he couldn’t find just one aspiring historian who “looked at the Movement through the prism of its similarity to military operations.” Credit: ebay. License: https://ebay.to/3IGklHN.

Rival militaries deploy murderous, organized mass violence against each other, and often civilians as well. Martin Luther King Jr., on the other hand, preached nonviolence and how to love your enemies. Ricks squinted hard at this contradiction and noticed that successful social movements and winning militaries share common qualities such as strategic thinking, discipline, careful organization, effective logistics, strong leadership, unit cohesion, calculated risk taking, and rigorous training.

Of course, these advantages are also shared by NFL teams that win multiple Super Bowls, the best run car dealerships, and all other uniquely effective enterprises. Sustained success is never an accident, even if it happens outside the battlefield.

But an examination of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference through the prism of the New England Patriots would probably make for a poorly received doctoral thesis and unleash a blizzard of football clichés.

So, Ricks went with the military analogies instead. This didn’t get him around the problem.

In the opening paragraph of chapter four of Waging a Good War, there is a digression about the overconfidence of the American colonial rebels after their initial successes against the British in the early days of the Revolutionary War. Like nearly all the book’s military analogies, this added little to the reader’s understanding of the story.

What was needed to be said—and the important lesson to be learned—was concisely observed at the end of that opening paragraph: “The civil rights movement overestimated itself going into the obscure southwestern Georgia town of Albany” and “the goals it set there were far too ambitious.”

But FOUR paragraphs afterward the would-be Sun Tzu of civil rights was still redundantly jargoning away: “The military term for setting goals that are too big is ‘overreach.’”

Yes, and that term means the same thing when an editor says it to you.

Waging a Good War is a sustained attack by analogy and bombardment by bromide.

On page 115, Ricks shared this: “Persistence is a neglected virtue in many walks of life, but it is prized in the military world—and was in the civil rights movement as well.”

Earlier, page 55 carried this warning: “A military maxim holds that one should never reinforce failure. Part of being a leader is being able to recognize when something is not working and then take steps to cut losses and move in a different direction.”

Then at the end of the same long paragraph: “Another part of being a leader is biding one’s time and waiting for the situation to develop.”

“But taking risks is almost essential to success in warfare,” according to page 186. “Avoiding them is a recipe for stalemate, at best.”

To summarize: Persistence is a virtue! Cut your losses and move on! Take Risks! Don’t overreach!

In any case, according to page 285: “War is cruel, exhausting and wasteful, even when one prevails.”

Does it improve the analysis if we retitle? Waging the Wasteful and Cruel Good War?

In confronting state-sanctioned racism on its home turf, the civil rights movement engaged a violent enemy far more formidable than any domestic opponent Americans face today. Of course, they succeeded because they provided a courageous moral example, but also and just as importantly because they had mostly done their homework and prepared carefully.

King obviously borrowed heavily from Mohandas Gandhi. Likewise, the strategy, tactics, and execution of the Montgomery bus boycott shares much in common with the boycotts against stamps, sugar, and tea practiced by colonial rebels in Boston two centuries earlier. And those behind the annual “March for Life” against abortion in Washington, DC, have obviously gone to school on the civil rights movement, learned its best organizing lessons, and have of late met with their own victories.

Successful leaders of all mass movements have devoured the history of their predecessors, learned from them, and improved upon them. The civil rights movement is a gold standard example from our history that is essential reading for all of today’s aspiring righteous mischief makers.

Those with little or no background in that history can gain it from Waging a Good War. The writing isn’t awful when it sticks to the story, rather than the tortured thesis.

But a richer diet on the same subject can be consumed far easier from other sources. Ricks would have been more helpful if he’d just written book reviews of his favorite sources.

In the next installment, Ricks tries to score points by comparing violations of voting rights in 2020 with those in the South before the civil rights era.