Labor Watch

Unionization Falls as Left Wing Pushes More Coercion

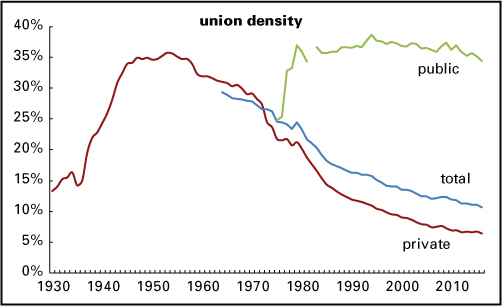

Credit: Doug Henwood/LBO News. License: Creative Commons.

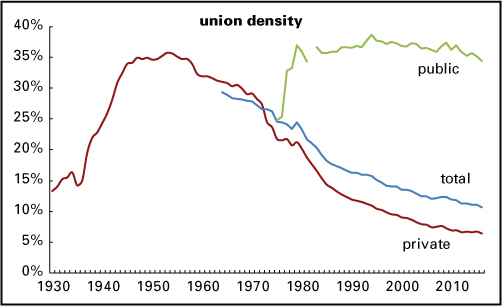

Credit: Doug Henwood/LBO News. License: Creative Commons.

Each year, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates the number of union members and the proportion of American workers in labor unions. Most years, the data tell a consistent story: American workers are increasingly not buying what organized labor is selling.

This year aligned with that story. The overall union membership rate tied its postwar low of 10.3 percent, with the number of unionized workers falling by an estimated 240,000 to 14.0 million. The unionization rate of private-sector workers reached a new record low of 6.1 percent in the BLS data set.

How Labor Got Here

When the BLS started collecting data on union membership, almost 17 percent of private-sector workers were union members. Today, that proportion (known as “union density” among labor scholars) has fallen by nearly two-thirds.

What happened? If you ask organized labor, it’s all the government’s fault for not putting enough of a thumb on the union side of the organizing scale. Winning secret-ballot elections in workplaces when employers can present information in opposition to union campaign promises is simply too darn hard. That is why Big Labor pushes legislation like the PRO Act or its failed predecessor, the “Employee Free Choice Act” card-check bill, that would increase its ability to coerce workers to join and fund labor unions.

The Private Sector Changed

In reality, the decline of organized labor is largely organized labor’s own fault. The first cause is the rules and costs that union contracts impose on employers, which render employers less competitive and less able to keep union members employed.

When unionization was at its height immediately following the Second World War, the world was a much different place. Western Europe and Japan had been destroyed by the conflict, China was falling to the Communists who would destroy its economy and generate man-caused famine, Eastern Europe was falling under the Soviet yoke, India was creating its “License Raj” of sclerotic socialist industrial policies, and Latin America was largely ruled by authoritarians following import-substitution industrialization policies that froze their economies. In that world, America was an industrial titan with no real economic competitors, so dividing the spoils of perpetual profit between capital and labor was possible.

Today, all those facts have changed, but Big Labor’s demands have not. As a result, some unionized firms have gone bankrupt, while others have offshored production. Other companies have moved production domestically to states with lower unionization and less union power, so they don’t go bankrupt and can keep their employees working.

It’s Also the Socialism

The second cause of Big Labor’s decline is the increasingly fanatical political agenda driven by the faction that isn’t falling in relative proportion to the relevant workforce: government workers. In 1983, when the BLS started estimating union density, about 37 percent of government workers were union members. While private-sector union density has since fallen by two-thirds, government-worker union density fell by only 3 percentage points.

These relative changes mean that the balance of power within organized labor is much different than when AFL-CIO heads George Meany and Lane Kirkland refused to support the presidential candidacy of Sen. George McGovern (D-SD) in 1972 over the senator’s excessive leftism.

In 1995, the government worker unions showed their ascendancy when then-SEIU head and reported Democratic Socialists of America member John Sweeney took control of the AFL-CIO by squeezing out Lane Kirkland’s successor in the union’s presidential election.

Almost 30 years later, the results are clear. In addition to providing near-monolithic support to Democratic political candidates and committees, the AFL-CIO celebrates “International Pronouns Day” while its president Liz Shuler demands Netflix cancel Dave Chappelle and has circulated Marxist propaganda calling on people to “seize the means of production.”

Desperate Struggles

While changes in the international economy and changes in the labor movement itself have clearly made unionism less appealing to the average private-sector worker, organized labor will not go quietly into the night. That is why it is pushing the PRO Act.

Rather than reform themselves, labor unions would rather get the government to rig the system to make it easier for them to promise the world to workers while delivering little more than campaign contributions to the politicians who vote for bills like the PRO Act. It is also a warning to the “labor conservatives” who hope to reach out to working Americans through unions as institutions. The working class they are looking for—typically the manufacturing or private-construction line worker—mostly left Big Labor long ago because Big Labor left him behind.